Source: IMG_5419 by controlarms, Flickr

Source: IMG_5419 by controlarms, Flickr

I don’t know about yours but my dictionary suggests that the word consensus means ‘general agreement’ or ‘majority opinion’. The reason I raise the issue is that over the past month, negotiators from some 170 countries have been discussing a UN arms treaty, which needed to be adopted by ‘consensus’ – any individual country could in effect ‘veto’ a deal.

And, in yet another act of monumental political cowardice that is precisely what happened.

Throughout the negotiations, countries such as Syria, North Korea, Iran, Egypt and Algeria opposed arms control but it was the United States (and Russia and China) who ultimately ‘triggered’ the unravelling of the potential deal. More time, they said to enable ‘consensus building’.

Clearly the consensus sought here is not that of those who continue to die (at a rate of approximately 2,000 per day) in conflict regions and countries; nor that of those whose human development is denied as their governments squander scarce resources on the latest technology and equipment nor the ‘consensus’ of the victims and their families following the recent Colorado ‘Batman’ killings. The consensus sought is actually for the vested interests and industries that support the use of arms – the gun lobby in the US and their total opposition to any restrictions (especially on the eve of an election); the consensus of the $US 60 billion plus global arms industry accounting for some 2.7% of global GDP and the consensus of the 6 EU member states in the top 10 arms exporters, along with the US, Russia, China and Israel.

The link between the arms industry and human development was eloquently sketched by Oscar Arias Sanchez, President of Costa Rica from 2006 to 2010 when he argued in 1998:

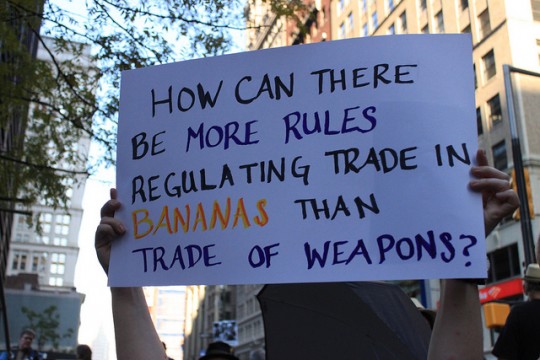

When a country decides to invest in arms, rather than in education, housing, the environment, and health services for its people, it is depriving a whole generation of its right to prosperity and happiness. We have produced one firearm for every ten inhabitants of this planet, and yet we have not bothered to end hunger when such a feat is well within our reach. Our international regulations allow almost three-quarters of all global arms sales to pour into the developing world with no binding international guidelines whatsoever. Our regulations do not hold countries accountable for what is done with the weapons they sell, even when the probable use of such weapons is obvious.

For more, see Oscar Arias Sanchez’s speech from the Nobel Peace Laureates Conference , November 1998.

The draft Arms Trade Treaty would have required countries to assess if any proposed arms export deal could be used to commit or support a serious violation of international humanitarian or human rights law. It covered all conventional arms from battle tanks, armoured combat vehicles, large-calibre artillery systems to combat aircraft, attack helicopters, warships, missiles and missile launchers, and, significantly also included small arms and light weapons. The draft treaty would require all countries to establish national regulations to control the transfer of conventional arms and to regulate arms brokers and would only have come into effect after it was ratified by 65 countries.

When implemented, the treaty would ensure that no arms deals would be permitted if there were ‘substantial risk’ that they could be used:

- in serious violations of international human rights or humanitarian law or acts of genocide or crimes against humanity (on this, see Geoffrey Robertson, 1999 Crimes Against Humanity: The Struggle for Global Justice, London, Penguin)

- in gender-based violence

- in terrorist attacks, violent crime or organised crime

- to violate UN Charter obligations, including UN arms embargoes

- to ‘adversely affect’ regional security

- to seriously undermine poverty reduction or socioeconomic development

One of the keywords used during the discussions over the past number of years has been ‘irresponsible’ arms deals which, of course begs the question as to what a ‘responsible’ arms deal would be given current international human development needs.

Many countries, including the US, control arms exports but to date there has never been an international treaty regulating the international arms trade. Countries such as Argentina, Australia, Costa Rica, Finland, Japan and Kenya have worked together to push a deal through. The UN General Assembly voted in December 2006 to work toward agreeing a treaty but significantly, the US, under George Bush opposed the move. In October 2009, the Obama administration reversed the Bush administration’s position and supported a General Assembly resolution to hold four preparatory meetings and the recent four-week UN conference to draft the treaty.

According to Suzanne Nossel of Amnesty International USA described the US action as:

…stunning cowardice by the Obama administration, which at the last minute did an about-face and scuttled progress toward a global arms treaty, just as it reached the finish line … it’s a staggering abdication of leadership by the world’s largest exporter of conventional weapons to pull the plug on the talks just as they were nearing an historic breakthrough.

However, all is not lost by any means, committed governments and campaigners are optimistic that an effective Arms Trade Treaty is ‘within reach’ as a significant majority of governments have indicated they will continue to work for the treaty which will now most likely be sent back to the UN General Assembly in October where the struggle will once again commence. But an international arms treaty without the US will be effectively void; something we should all act to ensure does not happen.

The consensus now needed is that such a treaty is long overdue and would reflect the views of the majority of citizens worldwide.

For more on the campaign and the need for arms control, see https://www.controlarms.org/home

Source: Think Twice by controlarms, Flickr