‘Sensationalised poverty media’ has usually been referenced as ‘poverty porn’ in discussions on development issues, but I have purposefully decided to not use this term as I find it a sensationalised term which distracts from the debate. Furthermore, it may be unsuitable for some readers of this blog.

When I reference sensationalised poverty in this blog, I am referencing media which exploits the people of the developing world in an undignified manner in order to evoke a response from the developed world, or world of charity ‘donors’. Check out the ‘Rusty Radiator Awards’ for examples. They (often hilariously) break down the best and worst of development communications each year.

This Dochas video also explains clearly the ongoing debate on the ethical use of photos and visual messages in the international development sector, arguing that their code of conduct should be adhered to by the NGO sector in Ireland.

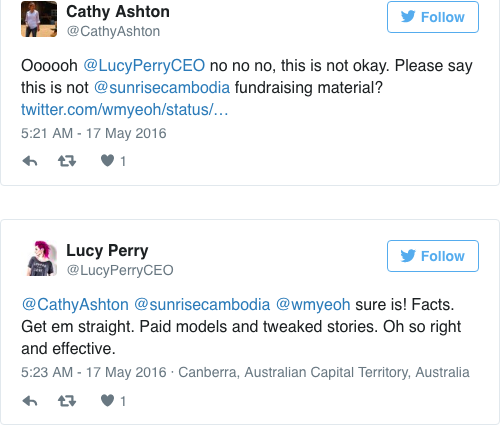

Recently, the following Twitter spat went down between A CEO of an NGO in Cambodia and some of her followers:

The question of whether paying models to partake in sensationalised poverty media for fundraising is unethical is an interesting one. Ultimately I argue that no, paying models to sensationalise poverty is still not ethical practise.

It is understandable that it seems the only way to fundraise enough money to continue the work of one’s organisation is to explicitly showcase the harrowing conditions you are fighting against. But the good does not outweigh the harm, and if you can’t figure out how to move beyond crude charity to greater systemic change in the world, then you need to reflect on what agenda you are truly working on.

Firstly, this question of paid models does not negate the ‘immediate need’ versus ‘long term development’ that plagues the development sector. In fact, it damages long term development goals. As Dambisa Moyo points out [on Africa], there is a a ‘Micro-Macro paradox’ where in the short term humanitarian aid seems to work, but taken within the context of the wider picture of the political and economic landscape, this form of fundraising aid does not work to support development in the long term.

So while these hard hitting images may raise funds in the short term, they are doing this at the detriment to the long term development goals of the world. We have seen time and time again that the ‘Western saviour’ complex does not work in relation to securing development, and yet sensationalising poverty that strips developing countries of their dignity solidifies the ‘white mans way’ [or the white man’s burden as William Easterly would put it] as the only way.

Secondly, paying models for sensationalised poverty media does not bring the average person from the “developed” world on any sort of learning journey that’s needed to collectively navigate to a better place.

Crudely put, I think most people in the West know that the world has some serious problems. I think the average person on the street could tell you that extreme poverty and hunger exists, and that there are changes to be made to make the world a better place.

However I don’t think that the average person yet knows what we need to do in order to aid development across the globe, or why we ALL have a role to play. Assuming long term development and a better world is the collective agenda of those in development organisations, surely communicating educational messages of change, hope, dignity and rights is what we should be doing, rather than shocking people in a moment to reach into their pocket, donate and then go about their day forgetting that they have just seen.

Finally, there are micro level ethics to consider too. If the person in the sensational poverty media is an adult, can we say that they can freely choose to partake in the media? Yes they might be paid, but if your need for money to feed your family is great enough, the actors may be forced to forgo their comfort levels and dignity. So they might say they freely choose this job, but at what cost? Is that really a fair choice?

The same and more can be said in the case of paid child actors. Can they give full consent if they do not understand the political context? Do they get to make the choice, or does familial financial pressure make the choice for them? Are child protection issues fully understood and considered before these images are published? It seems unlikely, especially when children are portrayed as being involved in the sex trade (traffic) or prostitution rings. What dangers does that open the child actor up to?

Overall, when we unpack the ethics of paid actors in sensational poverty media we can see that it raises both the same and new ethical red flags as before. While hard hitting images may raise funds in the short term, we cannot charitably pay our way to a better world; systemic change will require more work, mindful consideration and respect then that.