Following on from last year’s political developments in the United States and the UK, it has become popular to argue that democracy is under immediate threat or that it has been set aside.

This argument seems all the more plausible when one moves outside the traditional ‘western’ perspective to include countries such as China, Turkey, South Africa, Brazil, Myanmar, Poland, Ethiopia and Zambia (there are many more). Yet, much of the commentary remains resolutely European – we can no longer accept with confidence the long-term cohesion and strength of the EU nor can we accept that democracy and human rights remain cornerstones of American foreign policy (for many of us, they never were. Witness in recent years the devastation of Iraq and the ongoing indiscriminate and illegal bombing of Yemen). Fledgling democratic institutions in Central Europe are under serious attack especially in Poland and Hungary. And then there is Syria.

It seems that the rise of Trump, the emergence and partial success of proto-fascist parties in Europe, the debate on migration and diversity highlights an appetite for politicians willing to tell people that their problems are caused by some ‘other’ – foreigners, welfare scroungers, ‘the politically correct’ and, of course, the liberal media. Citizens increasingly disenfranchised and disempowered by mainstream economics and politics (and politicians) especially since 2007/08 remain vulnerable and unsure who to hold accountable. Representative democracy appears to be failing badly.

But, is this the full or even accurate picture…I think not.

Analysis of trends and patterns in countries such as Colombia, Hong Kong, Tunisia, Ghana, Botswana and even Nigeria suggest a counter trend as does the rise of Podemos in Spain, the Occupy, the divestment and the Gender Equality movements, the opposition of Bernie Sanders in the US and of Jeremy Corbyn in the UK all highlight a public appetite for an alternative politics. Recent and sustained successes on women’s rights in Jordan, Morocco, India and Brazil are more than simply signs of hope – they represent real progress. It is also important to acknowledge the very significant decline in populations under the control of military dictatorships in the past four decades.

| Democracy – a note on definition

The word from Medieval Latin democratia (13c.), from Greek demokratia (or ‘popular government’ – from demos ‘common people’ and kratos ‘rule or strength’. Often referred to as ‘rule of the majority’ with four generally accepted key components – a political system for choosing and replacing the government through free and fair elections; the active participation of the people, as citizens, in politics and civic life; the protection of the human rights of citizens and the rule of law applied equally to all citizens (Stanford Professor Larry Diamond). |

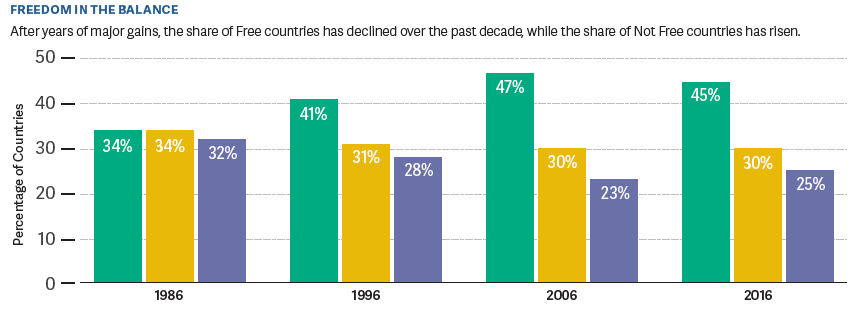

The evidence therefore suggests that despair is unwarranted just as equally as is complacency – democracy is the stuff of politics and, as such, is subject to cycles, patterns and trends – there is no one trajectory.In assessing the rise and decline of democracy it is necessary to take the long view rather than focusing on the immediate or even the short-term. Such an approach reveals that democracy began to make significant progress internationally in the period 1975 – 85 and advanced even further in the following decade. This was followed by a decade of reduced progress with only modest gains recorded – commentators argue that the ‘peak’ was reached in 2000. Since then, the pattern has been one of ‘stasis’ or very minor decline, nothing like the reversals often popularly referred to.

So what can we say about democracy worldwide today?

One of the most comprehensive reviews of this agenda is the Freedom in the World Report published annually by the US-based human rights, freedom and democracy organization Freedom House.

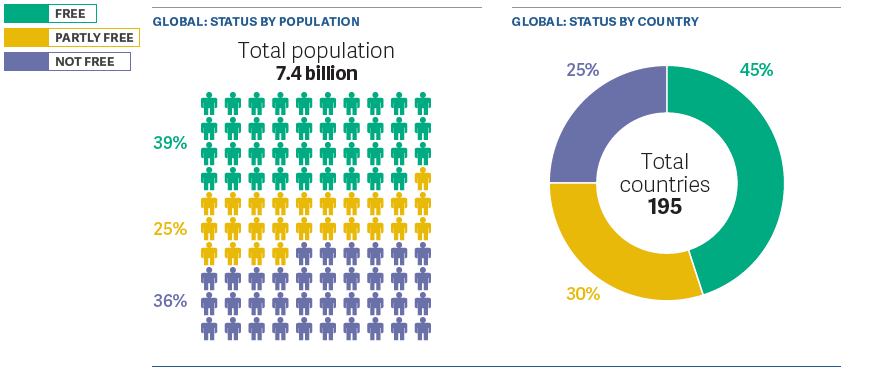

Its annual report evaluates the state of freedom in 195 countries and 14  territories during the previous year; its methodology derives from the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and assigns each country a score based on 25 indicators. These scores are, in turn used to determine two numerical ratings, one for political rights and the other for civil liberties (1 represents the most free and 7 the least). These ratings then determine a country’s overall status as Free, Partly Free, or Not Free. As the 2017 Report states:

territories during the previous year; its methodology derives from the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and assigns each country a score based on 25 indicators. These scores are, in turn used to determine two numerical ratings, one for political rights and the other for civil liberties (1 represents the most free and 7 the least). These ratings then determine a country’s overall status as Free, Partly Free, or Not Free. As the 2017 Report states:

‘Freedom in the World assesses the real-world rights and freedoms enjoyed by individuals, rather than governments or government performance per se. Political rights and civil liberties can be affected by both state and non-state actors, including insurgents and other armed groups.’

The 2017 Report, Populists and Autocrats: The Dual Threat to Global Democracy provides a comprehensive overview of the situation of democracy worldwide.

In summarising the current snapshot, the Report’s editors Arch Puddington and Tyler Roylance note the following:

‘All of these developments point to a growing danger that the international order of the past quarter-century—rooted in the principles of democracy, human rights, and the rule of law—will give way to a world in which individual leaders and nations pursue their own narrow interests without meaningful constraints, and without regard for the shared benefits of global peace, freedom, and prosperity.

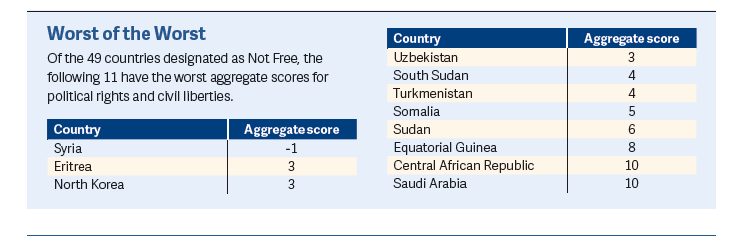

The troubling impression created by the year’s headline events is supported by the latest findings of Freedom in the World. A total of 67 countries suffered net declines in political rights and civil liberties in 2016, compared with 36 that registered gains. This marked the 11th consecutive year in which declines outnumbered improvements.

While in past years the declines in freedom were generally concentrated among autocracies and dictatorships that simply went from bad to worse, in 2016 it was established democracies – countries rated Free in the report’s ranking system – that dominated the list of countries suffering setbacks. In fact, Free countries accounted for a larger share of the countries with declines than at any time in the past decade, and nearly one-quarter of the countries registering declines in 2016 were in Europe.’

Possessing a solid ‘take’ on the realities of democracy worldwide today is a key first step in assessing our duties and responsibilities for the immediate future.

- Watch this space for Arguing Democracy part 2…

Photo credit: Bangkok (Jan 10th 2014) by Adaptor-plug CC BY-NC 2.0 via Flickr