The Report of the Special Rapporteur on extreme poverty and human rights, Philip Alston presented to the UN Human Rights Council 44th session, 15 June – 3 July 2020. Alston’s report offers an accurate and detailed overview of the current state of evidence and debate on extreme poverty worldwide.

developmenteducation.ie has produced a summary of its key points and arguments.

1. There has been a ‘dramatic and longstanding’ neglect and ‘downplaying’ of extreme poverty by many governments, economists, and human rights advocates. Covid-19 ‘a pandemic of poverty’, a deep economic recession and a worldwide movement challenging racism challenge us all with an ‘existential crossroads’. ‘Climate apartheid’, continued lack of basic rights such as healthcare, housing and education as well as the use of repressive policies will make matters worse.

‘While there is no magic bullet, taking extreme poverty seriously would address one of the main causes and consequences of these problems.’

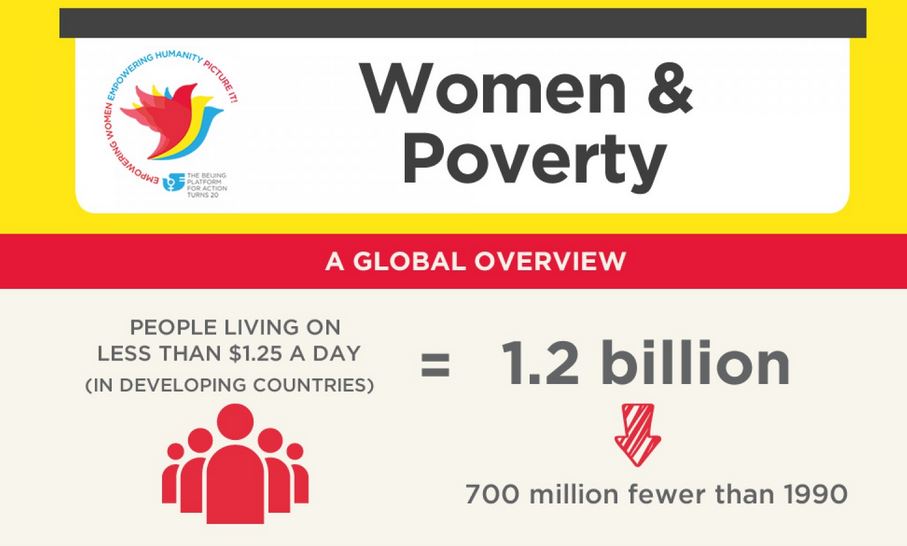

2. The claim that extreme poverty is nearing eradication is unjustified– it cannot be defended by the facts, it generates inappropriate policy and it promotes complacency – the reality presents ‘a far more troubling picture’. The claim is based on the World Bank’s measure of extreme poverty ($1.90 per day); under the Bank’s definition of the international poverty line (IPL), extreme poverty fell from 1.895 billion in 1990 to 736 million in 2015 – from about 36% to 10% of the world’s population.

This definition has been misused and is ‘far from complete’ – it has 6 fundamental weaknesses:

- It displays ‘a scandalous lack of ambition’ (the IPL is ‘staggeringly low’ – too low to be meaningful).

- It is not realistically linked to the real cost of the most basic of needs.

- It insists on a ‘one-size-fits-all’ model and ignores the global reality.

- It fails to take account of gender inequalities.

- It overlooks whole groups of people such as the homeless, migrants, stateless etc.

- It constantly underestimates the impact of China’s role in bringing down the world headcount of those in extreme poverty. While the Bank recognises the weaknesses of the definition, its response has been ‘resolutely ambivalent’ and ‘it continues to give the IPL top billing in its messaging.’

3. Using a more defensible IPL generates a radically different picture – ‘the extent of global poverty is vastly higher and the trends discouraging.’ Rather than one billion people lifted out of poverty and a global decline from 36% to 10% many IPL lines show only a modest decline in the rate of poverty and a nearly stagnant headcount. The number living under an IPL of $5.50 line held almost steady from 1990 to 2015, declining from 3.5 to 3.4 billion and the rate dropped from 67% to 46%.

Today, the leading global non-monetary measure of deprivation, the Multidimensional Poverty Index (covering 101 developing countries) yields a poverty rate of 23%.

‘COVID-19 is a pandemic of poverty…’

Philip Alston, 2020

4. The impact of COVID-19 will be long-lasting – according to the World Bank, the pandemic will erase all poverty alleviation progress over the past three years and will push 176 million people into poverty at the $3.20 poverty line. Many governments have seen COVID-19 as ‘a passing challenge to be endured’, others have taken it as ‘an opportunity to undermine or restrict human rights.’ The public health community’s mantra ‘stay home, socially distance, wash hands, and see a doctor in case of fever’ highlights the plight of the vast numbers who can do none of these things. ‘They have no home in which to shelter, no food stockpiles, live in crowded and unsanitary conditions, and have no access to clean water or affordable medical care.’

5. While the SDG process has been a ‘game-changer’ in important ways and has been used to very good effect in many settings ‘promoting awareness, galvanizing support, and framing the broader debate around poverty reduction’ and often providing ‘the only available entry point for discussions of contentious issues’, 5 years after their adoption it is time to acknowledge their failings and the ‘deeply disappointing results to date and a range of new challenges.’

The SDG agenda is inadequate and it’s targets set do not actually seek to eliminate poverty and would leave billions facing serious deprivation; shows a serious lack of ambition in seeking to reduce the proportion of people in poverty by just half in a period of unparalleled wealth and inequality; it stops conspicuously short of effective social protection calling for vague systems which might address the issue.

The SDGs call for a reduction in inequality within and among countries with the rallying cry ‘leave no one behind’ yet as noted by Oxfam ‘economic inequality is out of control.’ While inequality is ‘soaring’, the annual SDG report ‘treats inequality as just another box to tick.’ And this ‘superficiality epitomizes the broader failings of the SDG process to engage meaningfully with inequality’.

The SDG agenda ‘conveniently sidesteps necessary questions around wealth redistribution, elite capture of economic gains, growth achieved through carbon emissions, and inequitable fiscal policies. It treats inequality reduction as a problem to be solved through overall income growth, which flies in the face of recent history and is even more deeply problematic in light of the impacts of COVID-19 and climate change.’

‘And despite the importance of tackling gender inequality, at the current rate of economic growth, closing the gender gap in economic opportunity is projected to take 257 years.’

The SDGs have had little impact in slowing global warming; their focus on economic growth ‘without due consideration for its environmental impact or the extent to which it is currently tied to emissions and extraction is deeply problematic.’

While the SDGs constantly make reference to ‘transformation, empowerment, collaboration, and inclusion’, these concepts are illusory’ if people are unable to exercise their human rights. ‘Despite almost 20 mentions of human rights in the text, there is not a single reference to any specific civil and political right, and human rights in general remain marginal and often invisible in the overall SDG context.’

‘Unfortunately, SDG reporting too often tends to describe the glass as being one-fifth full rather than four-fifths empty.’

‘…the commitment to “a revitalized Global Partnership,” promoting “solidarity with the poorest and with people in vulnerable situations,” is lost in the fog of an overriding focus on Public-Private Partnerships with troubling track records.’

Instead of promoting empowerment, funding, partnerships, and accountability, too much of the energy surrounding the SDG process has gone into ‘generating portals, dashboards, stakeholder engagement plans, bland reports, and colorful posters. Official assessments are rarely critical or focused, and they often hide behind jargon.’

‘Continuing resistance in most countries to decoupling economic growth from fossil fuels, despite the opportunities presented by the COVID-19 emergency, makes the SDG growth targets almost impossible to achieve without far exceeding the Paris Agreement’s inadequate limit of 2°C of global warming by 2100.’

The pressing challenge is to reflect on ways in which the overall package, including targets and indicators, can be re-shaped and supplemented in order to achieve the key goals which otherwise look destined to fail.

‘Business as usual should not be an option.’

6. ‘Continued large-scale global poverty is incompatible with the human right to an adequate standard of living, and the right to life alongside the right to live in dignity. The failure to take the necessary steps to eliminate it is a political choice and one that leaves firmly in place discriminatory practices based on gender, status, race, and religion, designed to privilege certain groups over others.’

Refocusing the SDG agenda and ending poverty requires a direct focus on a wide range of issues including reconceiving the relationship between growth and poverty elimination; income redistribution, tax reform and tax justice, debt forgiveness and serious consideration of mechanisms of social protection.

‘The OECD, World Bank, and IMF steadfastly avoid relating their efforts in any way to the existence of a human right to social protection. It remains, at best, just another policy option…very few governments have accorded priority to social protection, at least until massive protests prompt deeper reflection.’

Despite its growth and increased popularity, philanthropic giving is not a democratic or transparent process, moving efforts to address poverty behind closed doors. It remains a form of private political power, one in which wealth can dictate policy without regulation or accountability.

‘Above all, it is no replacement for an equitable tax system or robust publicly funded programs that fulfill the human rights of all people and work to eliminate extreme poverty.’

For all of the talk of participation and partnership, people who have experienced poverty are largely shut out of policymaking processes. Governments need to listen more and to foster genuine public discussion.

The current IPL should not be the main focus of the international community in characterizing the extent of global poverty. The UN should prioritize its own measures…the Bank should explore measures explicitly tied to basic needs and capabilities or, at least highlight measures that give a more complete picture including obtaining and sharing crucial data.

‘In evaluating poverty eradication, the international community should stop hiding behind an international poverty line that uses a standard of miserable subsistence. The UN should have the courage of its convictions and acknowledge that the scale of global poverty is far more accurately reflected in its own indicators and reporting.’

‘Extreme poverty is and must be understood as a violation of human rights’.

7. ‘To avoid sleepwalking towards assured failure while pumping out endless bland reports, new strategies, genuine mobilization, empowerment, and accountability are needed. Recalibrating the SDG framework itself in response to fundamentally changed circumstances is an urgent first step.’

Ever-greater reliance on the private sector to defeat global poverty, whether through PPPs or philanthropy, is a blind alley. This trend represents an abdication of responsibility by governments and international organizations.

‘Poverty is a political choice and will be with us until its elimination is reconceived as a matter of social justice.’

‘Only when the goal of realizing the human right to an adequate standard of living replaces the World Bank’s miserable subsistence line will the international community be on track to eliminate extreme poverty.’

- Access Philip Alston’s 19-page report The Parlous State of Poverty Eradication.

- Philip Alston is keynote speaker at the Rising to the Challenge 3-day conference led by the Irish Development Education Association from 6-9 October 2020.