What does it mean to be hungry?

The Food and Agriculture Organisation defines ‘chronic hunger’ as:

People who are chronically hungry are undernourished. They don’t eat enough to get the energy they need to lead active lives. Their undernourishment makes it hard to study, work or otherwise perform physical activities. Undernourishment is particularly harmful for women and children. Undernourished children do not grow as quickly as healthy children. Mentally, they may develop more slowly. Constant hunger weakens the immune system and makes them more vulnerable to diseases and infections. Mothers living with constant hunger often give birth to underweight and weak babies, and are themselves facing increased risk of death.

Source: www.fao.org/hunger/en/

Who are the hungry?

In 2009, it was reported that nearly one billion people in the world suffer from hunger. That means that 13.1% – one in seven people in the world – do not get enough food to be healthy and lead an active life.

In 1983 the United Nations appointed the first Special Rapporteur on the Right to Food with the specific mandate to receive information about and to highlight violations on the Right to Food; to cooperate with UN agencies and other international organisations and NGOs to put the Right to Food in practice around the world and to ensure that a gender perspective is incorporated as part of any strategy in addressing that right. The current Special Rapporteur, Professor Olivier De Shutter, describes four broad categories of people who make up the world’s hungry:

- Small landholders who depend on less than 1.5 hectares of land for their livelihood, a group that NGO Concern Worldwide has termed ‘the farming yet hungry’. This group is made up of nearly 500 million people, the majority of whom are women, who produce food for themselves and their families on small plots of land in remote rural areas. When their harvests run out, they often have little to eat and lack the financial means to buy sufficient or adequate food, which could see them through the ‘hunger gap’. Frequently they are located far from markets where they could sell their produce or buy goods and services that could increase their productivity.

- Agricultural labourers – of the nearly 450 million such labourers in the world nearly 200 million are hungry. Many of them work on large plantations and are employed on a seasonal basis, often without a contract or any legal or social protection.

- Artisan farmers are mostly comprised of indigenous peoples, who do not own land or are in waged employment. They depend on artisan fishing, raising livestock and the products of the forest. This group comprises approximately 10% to 15% of the world’s hungry.

- The urban poor – a rapidly expanding group with the percentage of urban residents in sub-Saharan Africa alone expected to rise from 30% to 47% by 2020 (in other words, by 60 million people a year). Many are forced, through varying circumstances, to move from rural areas to urban centres in search of employment as forced migration, large scale agribusiness and poor agricultural conditions eventually take their toll on the rural poor. Access to food in urban areas depends almost entirely on cash purchases, posing serious problems for those who lack a fixed income. Although a wider variety of food is available, the food consumed in urban areas is not necessarily of superior nutritional quality.

Sources: Olivier De Schutter (2010), ‘Facing up to the Scandal of World Hunger’, Trócaire Development Review: Maynooth and Michael Doorley (2012) ‘World Hunger Today’, 80:20 Development in an Unequal World, 6th Edition: Dublin

Women and children

Estimates show that women produce up to 80% of the basic food in many developing countries. The World Food Programme (WFP) argues:

Women are the world’s primary food producers, yet cultural traditions and social structures often mean women are much more affected by hunger and poverty than men. A mother who is stunted or underweight due to an inadequate diet often give birth to low birthweight children.

Around 50 per cent of pregnant women in developing countries are iron deficient Lack of iron means 315,000 women die annually from haemorrhage at childbirth. As a result, women, and in particular expectant and nursing mothers, often need special or increased intake of food. (source: Unicef 2009)

Children are also particularly vulnerable. An estimated 146 million children in developing countries are underweight as a result of acute or chronic hunger (Source: The State of the World’s Children, UNICEF, 2009). The WFP assert that child hunger is inherited, claiming that up to 17 million children are born underweight every year as a result of inadequate nutrition before and during pregnancy.

Where are the hungry?

98% of the world’s 926 million hungry people live in developing countries

- 578 million in Asia and the Pacific

- 239 million in Sub-Saharan Africa

- 53 million in Latin America and the Caribbean

- 37 million in the Near East and North Africa

- 19 million in developed countries

Three-quarters of all hungry people live in rural areas, mainly in the villages of Asia and Africa. For specific geographical exploration of hunger around the world, see The Hunger Map.

Why is there hunger?

In purely numerical terms, there is enough food available to feed the entire global population of 7 billion people. Food has never before existed in such abundance. Yet, one in nearly seven people in the world is hungry and one in three children is underweight. So why does hunger continue to exist?

9 causes of hunger

1. Low agricultural productivity:

44 million people live on small farms that do not produce enough food to feed their families. Aid to agriculture decreased from a high of 17% of global funds in 1982 to 3.7% in 2006. This reduction in aid, along with changes in agricultural trade, has meant that poor farmers have not had sufficient access to seeds, tools, training, fertilisers, extensions to credit or secure access to land. These gaps in education, equipment and material provisions are especially true for people in small rural villages where all the food is grown locally.

2. Agricultural Infrastructure:

Roads, warehouses, irrigation…these are the national building blocks that enable agricultural growth for a country. Without them farmers encounter high transport costs, lack of storage facilities and unreliable water supplies that limit agricultural yields and access to food. In the long-term, improved agricultural output offers the quickest fix for poverty and hunger. Although the majority of developing countries depend on agriculture, their governments economic planning often emphasises urban development. In the long-term, improved agricultural output offers the quickest fix for poverty and hunger.

3. Poverty Trap:

Poverty is the root of human underdevelopment and also a result of it. Many of the world’s poor are unable to afford sufficient and/or quality food. As a result, their diets tend to be based on starchy foods, such as rice and breads, with few fruits and vegetables or animal products, leading to low calorie intake and micronutrient deficiencies. This ultimately leads to malnourishment. Because hunger leads to low levels of energy and health problems, it can then lead to further impoverishment by reducing an individual’s ability to work, or learn which then leads to further hunger again. Malnourishment and hunger can also lead to reduced immune systems for people to fight off disease and sickness, making poor health both a cause and effect of living in poverty.

4. Gender Inequality:

More than 60% of the chronically hungry people in the world are women. Former UN Secretary General Kofi Anan argued that in the developing world; ‘Women are on the front lines. They grow, process and prepare; they gather water and wood and they care for those suffering from HIV and AIDS. Yet women lack access to credit, technology, training and services and are denied their legal rights such as the right to land’. It is all too common that women are undernourished and undereducated in their childhood due to the fact that, in a lot of countries, boys tend to be given priority over girls at the dinner table and also in school. They are then married at a young age and thus, give birth to their own children at a young age. If they themselves are malnourished and uneducated, their children will be born malnourished and the cycle continues.

5. Unjust Trade Regimes:

The terms of international trade are for the most part stacked against poor and developing countries. Currently, markets work against the poor in both directions. The poor cannot afford the price of food and, at the same time, they are unable to sell their produce on the market to earn a living. Reform of Europe’s Common Agricultural Policy and of World Trade Organisation rules is a priority and must allow for fair access to international markets.

6. Climate Change and Natural Disasters:

The worst affected hunger spots are found in regions of climactic extremes; areas which experience drought, flooding, unpredictable precipitation patterns, soil erosion and desertification (increasingly as a result of climate chance patterns).

7. Falling Remittances:

Worldwide, nearly US$300 billion was sent in remittances to developing countries in 2007 from relatives living outside their native country, surpassing global official development assistance (ODA) by 60%. With the global financial crisis and consequent increase in unemployment, many of these remittances have now dried up leaving family ‘back home’ even more vulnerable to poverty and hunger.

8. Overexploitation of the Environment:

Poor farming practices, deforestation, overcropping and overgrazing are exhausting the Earth’s fertility potential and spreading the roots of hunger. Increasingly, the world’s fertile farmland is under threat from erosion, salination and desertification.

9. Conflict and Poor Governance:

It is a fact that any country with a strong democracy has ever suffered from famine and it also true that many nations with the highest levels of hunger are also gripped by violent conflicts or civil wars. Since 1992, the amount of short or long term food crises caused by human action has risen from 15% to 35%. The majority of these crises are due to war and conflict. The connections between war and hunger are clear. People are forced to flee their homes due to conflict; they become internally displaced people or refugees; their access to food is limited and can be hindered further due to the blocking of emergency food supplies to ‘enemy areas’. War and conflict impact on people in many different ways, with hunger being one of the key impacts, possibly even leading to famine, as for example, in Somalia.

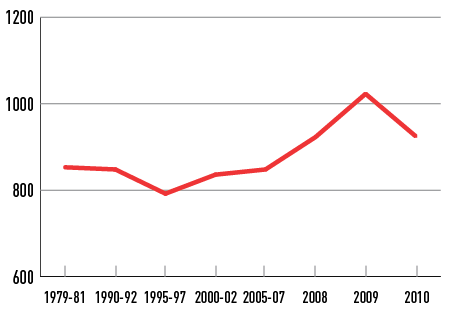

How many people are hungry? (millions)

Source: Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations (FAO)

What can be done?

According to the FAO, reducing hunger is achievable if both the causes and consequences of extreme poverty and hunger are dealt with, what they call the ‘twin-track strategy’. The first looks at improving the availability of food and then supporting the poor by in their productive activities. The second strategy is to target interventions that ?give the most needy families direct and immediate access to food.” At the same time, good governance at the national and international level is necessary to implement a successful global food system, where the principles of the Right to Adequate Food are promoted through transparent and accountable bodies that encourage, respect, empower and enable those most in need.

In 1996, the World Food Summit in Rome committed to cutting by half the number of undernourished people throughout the world by 2015. Using the FAO baseline of 850 million people (using the average of the period 1990-92), this means reducing the number of hungry down to 425 million people.

In 2000, the Millennium Summit in New York reaffirmed the 1996 commitment to reduce hunger and placed this goal as the first of the eight Millennium Development Goals. Goal 1 of the Millennium Development Goals aims at reducing the proportion of people suffering from hunger by half for the period between 1990 and 2015, thus reducing the proportion of people hungry as it relates to the size of the future world population.

The FAO MDG report for 2012 reveals that:

The most recent FAO estimates of undernourishment set the mark at 850 million living in hunger in the world in the 2006/2008 period—15.5 per cent of the world population. This continuing high level reflects the lack of progress on hunger in several regions, even as income poverty has decreased. Progress has also been slow in reducing child undernutrition. Close to one third of children in Southern Asia were underweight in 2010.

Sources:

- Olivier De Schutter (2010), ‘Facing up to the Scandal of World Hunger‘, Trócaire Development Review: Maynooth

- Michael Doorley (2012) ‘World Hunger Today’, 80:20 Development in an Unequal World, 6th Edition: Dublin

- UN Aids report (2006): New York.

- What causes hunger? – World Food Programme (2012)

- FAO Website: www.fao.org

- www.worldhunger.org