The majority of the world’s 7 billion people live in urban areas. More than one billion of these – or one in three urban residents – live in inadequate housing with no, or only a few basic resources such as access to safe water or sanitation, refuse collection, etc. Generally, these areas – often called ‘slums’ or ‘informal settlements – are acutely overcrowded. The majority of the dwellings are just one room, measuring barely over 100 sq. feet and most often occupied by large families. Many are makeshift ‘shacks’ assembled from scrap materials. As you can imagine these living conditions aggravate the spread of diseases, particularly when many of these living conditions are in countries that experience extreme weather conditions, such as high levels of heat, humidity and monsoons. Generally, people residing in these areas are among the world’s poorest and experience social, economic and political exclusion.

- For every 5 people in the world, 1 is without a home

- In the world today 1.5 billion people are without adequate shelter

- In third world countries, millions of people are without a home and completely exposed to the elements, due to poverty and natural disasters

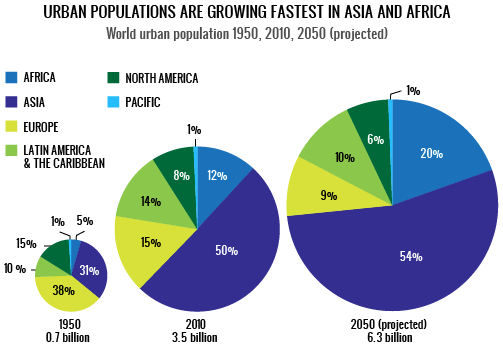

- Every year, the world’s urban population increases by approximately 60 million people

- By 2050, 7 in 10 people will live in urban areas

- 78% of city dwellers in the least developed countries live in slums

- By 2030 – some 5 billion of the world’s estimated 8.1 billion people will live in cities – about 2 billion of these will live in slums, mostly in Africa and Asia

- The reality in growth of ‘the slum’ is increasing at a rate of 25% per year

- Over 900 million people live in slums throughout the world

- There are over 250,000 slums in the world

Adapted from sheltertheworld.net/, 5:50:500 and UNICEF State of the World’s Children report 2012

The right to housing – a basic human right

The right to housing is recognised as a basic human right in various international instruments. The Universal Declaration of Human Rights, Article 25 acknowledges the right to housing and an adequate standard of living:

“Everyone has the right to a standard of living adequate for the health and well-being of himself and of his family, including food, clothing, housing and medical care and necessary social services, and the right to security in the event of unemployment, sickness, disability, widowhood, old age or other lack of livelihood in circumstances beyond his control.”

It is also included in other instruments such as the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (Article 11(1)); the European Social Charter (Article 16 and Article 31 of the Revised European Social charter); the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights. The right to housing is recognised under international human rights law, as clarified by the 1991 General Comment no 4 on Adequate Housing by the UN Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights.

At the 1996 Habitat meeting in Istanbul, the right to housing was a key issue and was one of the main themes in the Istanbul Agreement and Habitat Agenda. Steps were identified for governments to: “promote, protect and ensure the full and progressive realisation of the right to adequate housing”. Five years later at the 2001 Habitat meeting – called Istanbul +5 – the Istanbul Agreement and Habitat Agenda was reaffirmed along with the establishment of UN–HABITAT, which has the responsibility of promoting and raising awareness of the right to housing and in developing benchmarks and monitoring systems around the issues.

In supporting the MDGs, governments globally have recognized the importance of addressing the rights of people who live in slum settlements. Millennium Development Goal (MDG) 7, specifically targets the issue of slums in Target 11: by 2020 to have achieved a significant improvement in the lives of at least 100 million people who live in slum settlements.

Expanding urban growth

The greatest growth rate in the world’s urban areas is in low to middle-income countries, with most urban growth occurring in smaller cities and towns.

- Asia – home to half of the world’s urban population. The continent ranks 66 out of a 100 fastest-growing urban areas – 33 of these are in China alone. Cities like Shenzhen, increase at an annual rate of 10% (in 2008) and doubling in population every seven years.

- Africa – urbanisation growth rates in Africa are said to be increasing at an average annual rate of 4%. It is estimated that 37% of those living in Africa live in cities and is expected to rise to 53% by 2030. This is mostly experienced in countries of East, Central and West Africa. Populations in North and Southern Africa have been migrating in large numbers to urban areas for some time. The continent has a larger urban population than North America or Western Europe. More than 6 in 10 Africans who live in urban areas reside in slums.

- Europe – in contrast to rapid urban growth in the developing world, more than half of Europe’s cities are expected to shrink over the next two decades. The size of the urban population in high-income countries is projected to remain largely unchanged through 2025, with international migrants making up the balance.

Some Key Issues

Urban poverty – the impact on the world’s children

The UNICEF State of the World’s Children report 2012 focuses on the realities of children living in urban areas. Aggregate figures show that children in urban areas are better off than those living in rural areas given their assumed proximity to ‘modern facilities and basic services.’ The figures often do not reveal the reality of disparities faced by children and young people living in the world’s urban areas. What the UNICEF report highlights is that many of the children living in urban areas lack access to basic social services such as electricity, clean water, sanitation facilities and education. Living in urban slums exacerbates children’s health status. Their exposure to overcrowding and unsanitary conditions exacerbates diseases such as pneumonia and diarrhoea – two leading killers of children under the age of five worldwide – along with childhood diseases such as measles, tuberculosis and other vaccine-preventable diseases. The report shows that despite gains in overall global vaccine coverage, in slums and informal settlements the uptake of vaccinations remains low, negatively impacting on young people’s health. Children living in slums are exposed to hunger and malnutrition. They are less likely to go to school – due to limited education options, poverty, school overcrowding and poor quality. This forces many children and young people to live and work on the streets or join criminal gangs in order to survive. See the full report for more information.

Megacities and mega-regions – A 21st century phenomenon

The megacity of tomorrow… will be a place of life lived in the margins, where citizens have to work to carve their niche in a city that does not care.

Rem Koolhaas paraphrased in ft.com

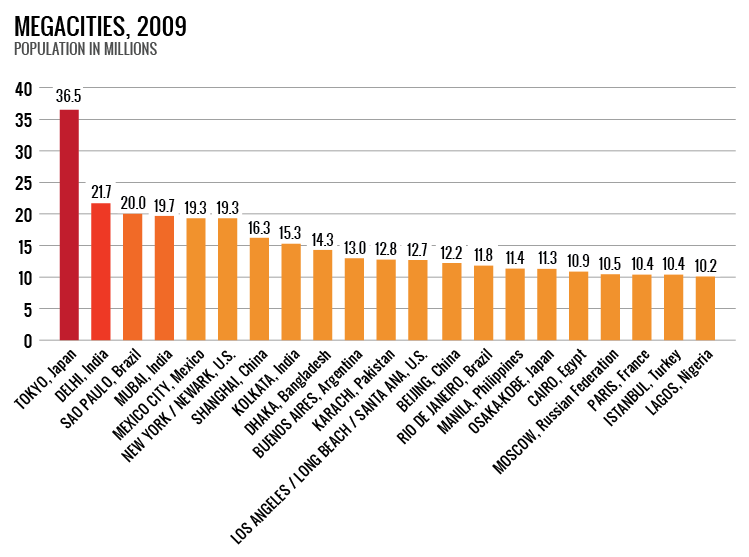

Nearly 10 per cent of the world’s urban population live in megacities – each with a population of more than 10 million people or more. In 2009 megacities accounted for 9.4% of the world’s urban population. London and New York have been on the megacity list since 1950! Tokyo joined the list in 1960. In 1975 Mexico City joined the megacity list. London is no longer on the list and New York is sliding rapidly sliding down the list. Now the list includes 21 cities, with all but 3 of them in Asia, Latin America and Africa.

Source: adapted from UNICEF state of the world’s children 2012.

A new breed of city – the ‘metacity’

Whereas megacities consist of populations in excess of 10 million people, a metacity is a city with a population of more than 20 million people. Tokyo with a population of more than 36 million people can be classed as a metacity, with emerging metacities all originating from what are ‘developing countries’ in India, Asia, South America and Africa.

In a Financial Times article, Edwin Heathcote describes one of the major threats to the rise of the metacity is inequality, where ?the wealthy begin to fear while the poor become envious. The result is ghettoised cities in which walls and gates become the norm as communities, often in close physical proximity, vie to exclude the other.? Metacities are difficult to govern, so encourage exploitation through accommodation for example means that the poorest in society are the most vulnerable. It also has negative consequences on the environment through the overuse of land resources, further pulling and pushing migration – and immigration to urban areas.

As cities and slums begin to ‘sprawl’ new urban configurations begin to take shape such as megaregions, urban corridors and city regions:

- Mega-regions: UNICEF defines a mega-region as ‘A rapidly growing urban cluster surrounded by low-density hinterland, formed as a result of expansion, growth and geographical convergence of more than one metropolitan area and other agglomerations.’ These regions have taken shape in countries of North America and Europe, but now also in other parts of the world as cities grow with greater concentrations of people, larger markets and economic expansion. Examples include: the Hong Kong-Shenzhen-Guangzhou megaregion (with 120 million people); China and the Tokyo-Nagoya-Osaka-Kyoto-Kobe megaregion in Japan (predicted to reach 60 million people by 2015).

- Urban corridor – cities that vary in size and are linked through transportation and economic agreements – claimed to promote regional economic growth and development. Examples include: the industrial corridor developing between Mumbai and Delhi in India; the manufacturing and service industry corridor running from Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, to the port city of Klang; and the regional economic axis forming the greater Ibadan-Lagos-Accra urban corridor in West Africa.

- City-region – An ‘city-region’ is a major city that expands beyond administrative boundaries and absorbs smaller cities, towns and semi-urban and rural hinterlands. This can also expand to the extent that it merges with other cities forming a metropolis that will eventually become a city-region. Examples include the Cape Town city-region in South Africa which extends up to 100 kilometres and the extended Bangkok region in Thailand, which is expected to further expand another 200 kilometres from its centre by 2020, substantially impacting on its current population of over 17 million.

- Landfill cities – With cities growing at a pace faster than local, government and NGOs can keep pace with and with the fight for ‘legal’ urban space, city areas around landfill sites are becoming home to many residents. As you can imagine, the conditions in these areas are extreme – the toxic stench and fumes, contaminated water, hazardous fuels and liquids, etc., all contributing to escalating diseases. To learn more about these communities see a photostory of Kodungaiyur in Chennai City, India. Source:https://thealternative.in/articles/trash-planet-kodungaiyur

So what does all this mean for the future? In his article, Heathcote asks ‘what hope is there for the exploding metacity…?’

‘It is impossible to predict the challenges that will face the city of the future. There will be problems of inequality, health, education, crime, governance, disenfranchisement, terrorism, war and loneliness. But there are other potential nightmares. Food, water, power and air are by no means guaranteed in a future defined by climatic catastrophe, pollution and massive overcrowding.’

Yet despite this, he feels that there is hope:

‘In spite of the nightmare scenarios, it is important to remember that London, the original megacity, has already survived these tribulations and it remains a desirable place to live. None of these problems is insoluble and the city remains, on the whole, a civilising place.

Slum, Informal Settlement – or both?

The UN definition of an informal settlement is an area ‘characterized by overcrowding, deterioration, insanitary conditions, or absence of facilities and amenities which, because of their conditions or any of them, endanger the health, safety and morals of its inhabitants and community.’

However, defining a slum or an informal settlement is becoming increasingly difficult – the two are often referred to interchangeably. However, there is a difference. Although some informal settlements look like slum settlements in which populations continue to live in poor conditions that reflect the characteristics of most slums, the term ‘informal settlement’ indicates the absence of regulated housing structures that result in informal structures. The structures are ‘legal’ to the extent that they are not under threat of eviction and are recognised by the community and authorities as earmarked for upgrading – but these are not slum settlements. Classifying a slum settlement into an informal settlement implies service provision and upgrading.

Slum settlements are most often regarded as illegal, so populations that live in them generally have no official address and are most often denied their basic rights and entitlements, such as access safe water, sanitation, utilities, healthcare services and education. People in illegal slum settlements live with the constant threat of eviction. Many areas are characterised by open sewage and uncollected refuse that clogs up drainage ditches and overflows in rainy seasons leading to flooding and encourages rat and cockroach infestations. Personal security is an issue, in particular for women and girls in poorer areas who fear rape or sexual harassment using the public latrines at night, which may be a distance away from their ‘shack’. Some slum settlements have become a permanent fixture that in places such as in Calcutta for example, they are being regularised and upgraded with minimal public facilities and service provision.