A contrasting viewpoint is offered by London School of Oriental and African Studies Professor Christopher Cramer who, having led a study of the impact of Fairtrade in Ethiopia and Uganda in 2014 [2] stated: ‘The British public has been led to believe that by paying extra for Fairtrade certified coffee, tea and flowers they will ‘make a difference’ to the lives of poor Africans. Careful fieldwork and analysis in this four-year project leads to the conclusion that in our research sites Fairtrade has not been an effective mechanism for improving the lives of wage workers, the poorest rural people.’

Like so many others issues of international development, Fairtrade and the Fairtrade Movement has generated strong and contrary viewpoints from supporters who claim fairtrade will radically change trade rules and improve the lives of the poor to critics who argue that fairtrade does not deliver what it promises, that is distorts markets unfairly and that it distracts attention from far more important issues.

Two quotes illustrate the debate:

A 2010 study of Fairtrade by Sushil Mohan [3] published by the institute for Economic Affairs (2010: 116-117) argued that

‘…the Fair Trade promotional campaigns tend to convey the impression that free trade is inherently inequitable and anything not carrying the Fair Trade mark was unfairly traded. This is inherently wrong because it fails to recognise that other trading relationships benefit consumers, producers and workers, and at times in less costly ways compared to Fair Trade.’

By contrast philosopher Julian Baggini [4] argues in his book The Virtues of the Table: How to Eat and Think (2014:81):

‘…in the real world, the question is, how should we act faced with the choice between buying goods in a distorted market that squeezes suppliers or buying goods that don’t contribute to this squeezing? The only ethically acceptable answer is obvious…’

The modern fairtrade movement (built on strong historical roots) is now some 50 years old and has a significant history and track record reflected in current debate and argument. Below, we present some of the main arguments offered in support of Fairtrade and those in the oppositional or critical tradition. In addition, we include some references for further reading and research.

The Debate

The moral debate

Agree 1

Not only is it morally wrong to exploit other human beings or to make them work for as little as possible or in poor or harmful working conditions, we also have a duty to respond to such circumstances by not knowingly purchasing products produced in such circumstances but, instead buying those that are ethically and morally ‘better’. While Fairtrade products, on their own, cannot fundamentally change the world, un-fairtrade products certainly will not and cannot be ethically defended. Fairtrade is a straightforward question of acting ‘more morally’ in the modern world.

Fairtrade is not a new idea, it has deep historical roots and represent a core strand in political, social and radical thinking across many centuries, histories and geographies.

Sources: this set of arguments is usually offered by philosophers, trade unionists, religious groups, trade activists, developing world commentators and also, interestingly and more recently some business people.

Disagree 1

As we are not responsible for the current state and shape of the world (which most of us cannot and do not effectively influence), we cannot be made responsible for ‘unfairly’ traded products (to do so would be, in itself ‘unfair’). If some businesses are exploitative, any guilt associated with such behaviour does not transfer over to ‘us’. Choosing Fairtrade goods over other goods would discriminate against workers and companies producing such goods, would lead to job losses and would lead to higher costs for consumers. Fairtrade is essentially a middle class ‘morality’ debate.

Sources: this set of arguments is usually offered by some philosophers (including many from the developing world), economic analysts, some ‘think-tanks’, many business associations and many major international product supply companies.

The economic debate

Agree 2

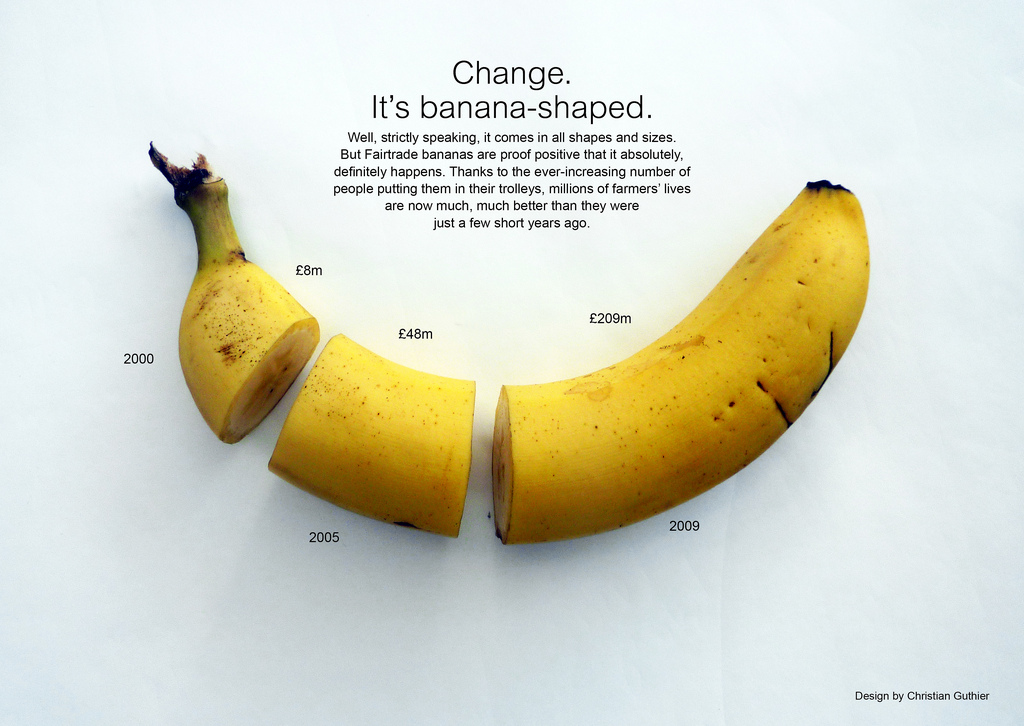

The Fairtrade Movement (there are now four international fairtrade networks) and its various products such as coffee, sugar and bananas witness a growth rate of 15% in 2014 to reach a total value of €5.7 billion [6]. The number of Fairtrade producer countries has now reached 74, while more than 30,000 Fairtrade products are on sale in 125 countries across the world (including in developing countries). There are now more than 1.4 million farmers and workers, belonging to 1,210 producer organisations (including local co-operatives) involved in Fairtrade initiatives. Due to increasing consumer demand for fairtrade products many supermarket chains and food distributors have included such products in their stores. Fairtrade demonstrates that an alternative trading ethic appeals to many people internationally and that a real market exists for such products.

Fairtrade has routinely (but not always) meant higher and fairer returns to developing world farmers and producers thus improving the lives of their families and communities in real and substantive ways. And, Fairtrade has highlighted many dominant ‘unfair’ trade practices worldwide.

Sources: again, this set of arguments are offered by the fairtrade movement globally, by by some economic analysts, faith-based groups, a growing number of politicians and public representatives, some business people and NGOs.

Disagree 2

Essentially, Fairtrade reflects the demands of (richer) western consumers rather than the real needs of developing countries (and the poorest people) – for example its prohibition on child labour may not always be ‘best’ for poor families, where it may be in the family’s interests for children to work to ensure survival or boost income and their own life-chances. The real change that is needed is the removal of obstacles preventing poorer countries developing beyond low-wage and subsistence primary production into higher value goods processing where profits are at their highest. Greater trade liberalisation is the priority as this would affect all goods and not just ethical schemes operating ‘on the margins of global trade’.

Sources: both politically left and right commentators (including many from the developing world), a number of conservative ‘think-tanks’, many business associations and many development economists

The impact debate

Agree 3

The core impact and purpose of Fairtrade is to improve the lives and livelihoods of Fairtrade producers in developing countries and this it has done. The fact that the numbers involved remain small in world terms does not undermine this argument in any way; Fairtrade continues to work to expand its scope and impact. In 2014, more than 28% of all Fairtrade farmers and workers were located in low-income countries. While Fairtrade may not have increased the income of everyone involved in Fairtrade production (this appears to be the case for many workers on Fairtrade plantations etc.), it has improved it for very many (including with subsidised food, housing, transport, healthcare, and education).

Fairtrade never claimed it could change the structure and functioning of world trade; it simply offered a fairer and effective alternative; a different way of doing things. And, it has offered millions of consumers an ethical choice and, in doing this it has raised the question of ethics in world trade in a manner not achieved to date.

Sources: Fairtrade foundations, networks, shops and activists worldwide; many academics and researchers (including Fairtrade critics), some trade unions and consumer groups, church-based groups and many environmentalists.

Disagree 3

In terms of impact, Fairtrade fails at a number of important levels. Firstly, the more extensive studies of its impact indicate that the poorest workers on many Fairtrade plantations or farms do not earn higher wages than in surrounding ‘non-Fairtrade’ farms; while farmers and owners may do so, the benefits are not always passed on. Secondly, the criteria for choosing Fairtrade producers is not clear and often those chosen are not by any means the ‘poorest’ (and the poorest countries still only represent 28% of Fairtrade producers). Also, the poorest are usually casual labourers who benefit little from Fairtrade, if at all. The criteria for choosing producers often discriminates against the poorest producers and workers.

Another significant issue is that Fairtrade through providing a minimum ‘baseline price’ for commodities, while allowing farmers to protect themselves against market volatility, builds ‘fairtrade dependency’ and effectively ensures that people ‘get charity as long as they stay producing the crops that have locked them into poverty’ (Professor Paul Collier) [4].

Finally, Fairtrade constantly overstates its value and impact suggesting that non-Fairtrade products depend on unfair and unjust practices – this is by no means the case as studies have shown.

Sources: many (but not all) researchers who have conducted detailed studies of Fairtrade, academics (especially economists), some think-tanks, many business groups, retailers and wholesalers outside the Fairtrade ‘family’ who have their own certification and fairness schemes and some ‘left’ oriented developing world commentators.

The political debate

Agree 4

To date, thousands of schools, universities, workplaces and even cities and towns have become fairtrade places and spaces; is this simply the result of clever lobbying and influence by a small number of people or is it the result of a deep-seated desire by people at all levels in society that their coffee, chocolate, cotton etc. are ethically sourced and produced? Fairtrade has succeeded because it strikes a deep cord in people’s moral being or psyche. It touches emotions and desires that ‘anonymous’ trade cannot.

Fairtrade has been debated and acted upon in many ways in state, national and international parliamentary fora as a result of research, argument and advocacy; it has stimulated international business and supermarket chains to address the ethics of some of their business policies and practices. Even the backlash against fairtrade alternatives is proof of its impact and relevance. Fairtrade threatens vested interests.

Sources: the fairtrade movement, NGOs, some political parties and groupings, many faith-based groups and structures; some academics and researchers and many workers rights and consumer groups.

Disagree 4

Just because a school, a university, a workplace, council or town/city becomes a ‘fairtrade’ place, does that mean that all its students/workers/inhabitants have agreed to this? Do they even support it or have a few influential people ‘made’ this happen and how democratic, consultative or representative is this process? Fairtrade remains a middle class flight of fancy and does not reach across all levels of society.

Fairtrade hides its ultimate political agenda (restricting free trade and free choice) under a carefully crafted and promoted ‘soft’ charity oriented wrapping. It represents the interests and agendas of political groups and organisations which many of its supporters do not recognise.

Sources: many conservative Think-tanks, many business groups, retailers and wholesalers, some researchers and academics and many politicians and local councillors.

The consumer debate

Agree 5

Fairtrade is simply one part of a hugely growing ‘alternative shopping’ culture which places considerable emphasis on issues other than cost and availability. ‘Ethical labelling and certification’ is a catalytic agenda in raising questions and debates about what is fair and unfair in our consumption choices. Being a consumer is a powerful weapon for good if used wisely and strategically. Fairtrade and like-minded groups have placed ethics on the trade agenda of governments, international institutions and businesses based principally on consumer power (or the threat of it). While shopping for and purchasing fairtrade products cannot undo the structural and systematic wrongs of a whole system, it can nonetheless send a very powerful message to politicians that consumers demand reform. It is a message they are now beginning to hear – loud and clear.

Fairtrade has also played a powerful, supportive role in ‘consumer education’ and represents a welcome antidote to (all too often) the dishonest misinformation that is advertising.

Sources: the fairtrade movement, many politicians, environmental and food activists, consumer affairs groups’ ‘ethical’ labelling organisations and, in recent years, some shops, retail chains and supermarkets.

Disagree 5

Fairtrade places primary responsibility for ethical trade and consumption and for ensuring that farmers and workers in the developing world are paid fairly and have decent working conditions on to the shoulders of essentially innocent consumers. The ‘middle class morals’ of Fairtraders are foisted on to others who may or may not be able to afford them or who have never been consulted on the issue. Those who do not shop fairtrade are tainted in some way, made to feel they do not care about others. Fairtrade products do not have a monopoly of products that are made and traded fairly.

Placing primary emphasis on consumers can also have the effect of diverting attention from where it rightly belongs – on big businesses, international traders, food manufacturers and retailers who are happy to have a few ‘fairtrade shelves’ in a sea of potentially ‘unfair shelves’. Fair trade based on consumers alone will never address the core obstacle of virtual monopoly markets dominated increasingly by powerful transnational corporations who control global terms of trade. What is needed is not consumer action but political action to force real change.

Sources: interestingly, these arguments come from the political left and right, from many developing world observers and critics of fairtrade, from academics and journalists, from some consumer groups and food activists.

References and readings

[1] Various articles debating fairtrade in the Guardian newspaper by Felicity Lawrence (2005 – 2012)

[2] Fairtrade, Employment and Poverty Reduction in Ethiopia and Uganda by Christopher Cramer et al (2014) Final Report to DFID SOAS London.

[3] Fair Trade Without the Froth: A Dispassionate Economic Analysis of ‘Fair Trade’ by Sushil Mohan (2010) London Institute of Economic Affairs

[4] The Virtues of the Table: How to Eat and Think by Julian Baggini (2014) Granta | book

[5] The Bottom Billion by Paul Collier (2007) Goodreads United kingdom | book

[6] Monitoring the scope and benefits of Fairtrade Sixth Edition by Fairtrade International (2014)

[7] ‘Fairtrade is an unjust movement that serves the rich’ by Ndongo Samba Sylla ( September 5th 2014) The Guardian newspaper

[8] Unfair Trade by Marc Sidwell (2008) Adam Smith Institute London

[9] Monitoring the scope and benefits of Fairtrade Seventh Edition by Fairtrade International (2015)

[10] A History of Fair Trade in Contemporary Britain, From Civil Society Campaigns to Corporate Compliance by Matthew Anderson (2015) Palgrave Macmillan, London | book