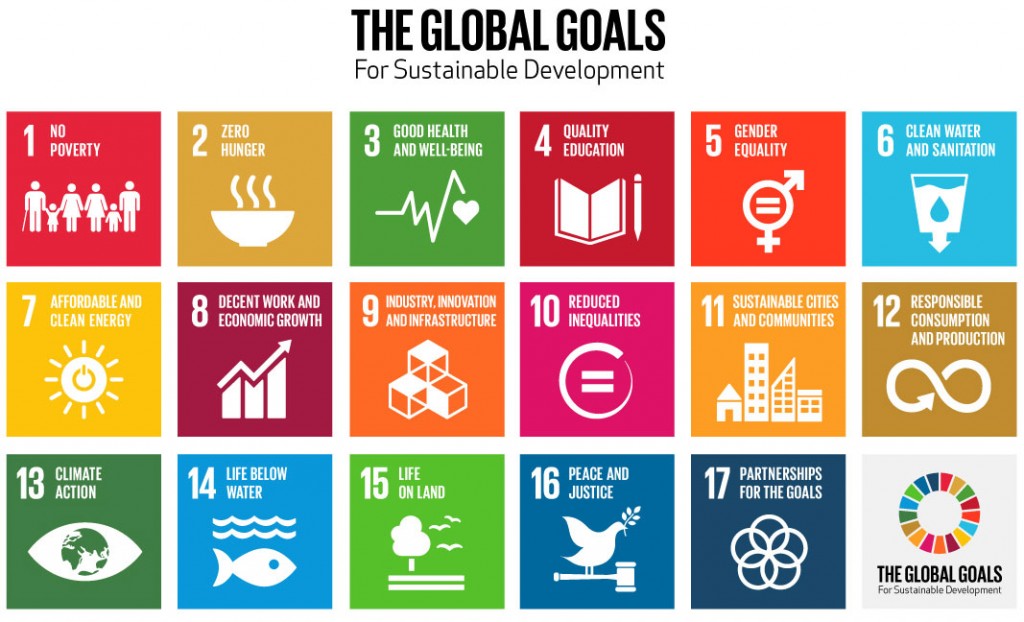

The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) are the international agenda agreed in September 2015 of action to tackle and end poverty, increasingly protect the planet and work towards ensuring that all people enjoy peace and prosperity.

This section introduces and explores the SDGs – dive in and see what they are all about, including the key challenges ahead if we are to achieve them by 2030.

What are the SDGs?

The Sustainable Development Goals (officially known as Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development or SDGs or often the Global Goals) are an international agenda of action to tackle and end poverty, increasingly protect the planet and work towards ensuring that all people enjoy peace and prosperity.

The 17 Goals seek to build further on the stated successes of the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) in areas such as literacy, health and education while also including new areas such as climate change, economic inequality, innovation, sustainable consumption and peace and justice. The Goals are seen to be interconnected reflecting the integral links between different dimensions of human development.

The SDGs argue strongly for a partnership-based approach to development as well as a practical and pragmatic agenda to improve life, in a sustainable way, for this and for future generations. The Goals are based on defined guidelines and targets for all countries to adopt in the context of their own priorities and the environmental challenges of the world at large. Officially, the SDGs are designed to tackle the root causes of poverty, to deliver increased basic needs especially for the poorest, tackle inequality and to do this in the context of protecting the planet and making current and future development sustainable.

On 1 January 2016, the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development came into force on January 1st, 2016 having been adopted by world leaders in September 2015 at a major UN Summit . They represent the most ambitious and significant agenda agreed internationally on the issues for the period to 2030. The new Goals call for action by all countries, poor, rich and middle-income and while not legally binding, expect governments take ownership of them and establish national frameworks for their achievement.

The Goals are built around the ‘5 P’s’:

People: ‘We are determined to end poverty and hunger, in all their forms and dimensions, and to ensure that all human beings can fulfil their potential in dignity and equality and in a healthy environment.’

Planet: ‘We are determined to protect the planet from degradation, including through sustainable consumption and production, sustainably managing its natural resources and taking urgent action on climate change, so that it can support the needs of the present and future generations.’

Prosperity: ‘We are determined to ensure that all human beings can enjoy prosperous and fulfilling lives and that economic, social and technological progress occurs in harmony with nature.’

Peace: ‘We are determined to foster peaceful, just and inclusive societies which are free from fear and violence. There can be no sustainable development without peace and no peace without sustainable development.’

Partnership: ‘We are determined to mobilise the means required to implement this Agenda through a revitalised Global Partnership for Sustainable Development, based on a spirit of strengthened global solidarity, focused in particular on the needs of the poorest and most vulnerable and with the participation of all countries, all stakeholders and all people.’

The SDGs are built around a set of 17 goals with 169 targets which can be summarised as follows:

- Ending poverty in all its forms everywhere;

- Ending hunger;

- Achieving gender equality;

- Ensuring healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages; and

- Ensuring access to affordable, reliable, sustainable, and modern energy for all.

More: download the official UN document on the SDGs and an excellent interactive summary on The Guardian.

Related Quotes

- ‘This Agenda is a plan of action for people, planet and prosperity. It also seeks to strengthen universal peace in larger freedom. We recognize that eradicating poverty in all its forms and dimensions, including extreme poverty, is the greatest global challenge and an indispensable requirement for sustainable development.’

– Preamble to Transforming our World: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development

- ‘This participation of the poor and the growing awareness of the urgency of true global development is where we hope the SDGs will differ from the MDGs. MDGs were created through a top-down, closed door process that did not engage people living in poverty, meaning that the goals often failed to respond to the experiences or priorities of people on the ground. This is our generational chance to make this right.’

– Stephen Kituku, National Director of Caritas Kenya

- ‘It must never be forgotten that political and economic activity is only effective when it is understood as a prudential activity, guided by a perennial concept of justice and constantly conscious of the fact that, above and beyond our plans and programmes, we are dealing with real men and women who live, struggle and suffer, and are often forced to live in great poverty, deprived of all rights.’

– Pope Francis, UN General Assembly, September 25th 2015

Where did they come from?

The SDGs represent the latest framework for describing, measuring and delivering human development following the demise of the traditional ‘economics only’ definition of development and its replacement by the far broader concept of ‘human development’ embracing not just the economic but also the social and political (and now environmental). This latter human development framework is captured each year in the Human Development Report published by UNDP.

In 2000, the UN Millennium Development Goals (MDGs, labelled by the UN as the ‘most successful anti-poverty movement in history’) were agreed for the period to 2015, the SDGs have followed on directly from this and were first outlined at the UN Conference on Sustainable Development in Rio de Janeiro in 2012. The MDGs established measurable, universally-agreed targets for tackling extreme poverty and hunger, preventing deadly diseases, and expanding primary education to all children, among other development priorities.

While the MDGs did not achieve all their objectives (and there is vigorous debate as to what progress can actually be attributed to the MDGs per se) the agenda did stimulate progress in several important areas: reducing income poverty, providing much needed access to water and sanitation, driving down child mortality and very significantly improving maternal health. They also kick-started an international movement for free primary education, encouraging countries to invest in future generations. Also, the MDGs made very real progress in combatting HIV/AIDS and other treatable diseases such as malaria and tuberculosis.

For an assessment of the MDGs, see the last progress report published in 2015.

In contrast to the MDGs which were drafted by a group of experts at the UN, the SDGs were developed by an intergovernmental Open Working Group (OWG) that comprised representatives of some 70 countries. Whereas the MDGs were about resource transfers from rich to poorer, the SDGs are deemed universal in that they are supposed to apply to all countries and try to overcome the idea that development is about poorer countries ‘catching up’ with richer ones.

Related Quotes

- ‘The final MDG report confirms that goal-setting can lift millions of people out of poverty, empower women and girls, improve health and well-being, and provide vast new opportunities for better lives.’

– The Millennium Development Goals Report 2015

- ‘The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development adopted unanimously at the United Nations by world Heads of States and Governments in September 2015 is highly ambitious. If taken seriously it has the potential to change the prevailing development paradigm by re-emphasizing the multidimensional and interrelated nature of sustainable development and its universal applicability.’

– Jens Martens Spotlight on Sustainable Development Report by the Reflection Group on the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development 2016

- ‘We either unite or collectively perish, as no single country or region can be an island of prosperity in an ocean of poverty, insecurity and underdevelopment.’

– Nkosazana Dlamini-Zuma, African Union Commission 2016

8 Key Arguments in support of the SDG agenda

1. If implemented effectively, the SDG agenda offers the most extensive and internationally agreed platform to date for tackling most of the key challenges facing humanity worldwide today. The agenda implicates all countries and is based on an extensive consultation process and, potentially involves all the key players – governments, civil society, business and a host of international organisations and structures led by the UNDP.

2. The MDG agenda highlighted many areas in which real and life enhancing improvements have been achieved e.g. health, child mortality, education, immunisation, access to water and sanitation etc. In a similar vein, the SDG agenda represents a pragmatic and realistic opportunity to build on these successes and to achieve even more thus impacting directly on the lives of many of the world’s poorest and most vulnerable people. Literally it is a framework to transform millions of lives.

3. Unlike the MDGs, the SDGs have been developed (and will be monitored and reviewed) through a consultation process that has been far more inclusive. Over 25 countries have initiated national consultations to develop national SDG policies adapted to their local contexts and realities. Also positive is the fact that civil society organisations and networks have started to create alliances across many sectors at national and international level, bringing together a broad range of environment, development, women’s rights and human rights groups as well as trade unions and social justice organisations. This critical engagement of civil society groups and the broader public is a central and key feature of the SDG process.

4. The SDG agenda has included many key areas ignored by the MDGs – climate change, inequality and conflict, for example. Many commentators and organisations worldwide were unhappy at the exclusion of what they saw as fundamental issues in the MDG framework. Many, if not most of these have now been included. While critics of the SDGs argue that having 17 Goals and 167 targets is far too expansive and makes the SDG too complex, advocates argue that the SDGs reflect the complexity of real life. This broader, more inclusive agenda potentially facilitates a greater base of support and engagement for the overall agenda.

5. An additional criticism of the MDGs was that they essentially focused on Developing Countries with Developed Countries playing a supportive role. The SDGs now emphasise the universality of the agenda, one that requires all countries – both rich and poor alike – to act locally and internationally. Many dispute the expectation that the goals can actually be achieved but without the SDG vision and process, the world will remain divided in its many traditional and failed blocs and processes. Something new is long overdue and the SDGs represent a vital and urgent opportunity to collaborate and experiment in the context of a universal movement for sustainability.

6. The SDGs significantly move forward the development, environment and equality agenda not only in terms of the issues to be addressed but also in terms of the participants expected to play a key role in addressing them. But crucially, the SDGs represent a quantum leap in terms of how progress will be measured and assessed. By setting specific targets and by establishing timeframes, the SDGs have emphasised the need for more accurate and dependable data to underpin the assessment of progress or otherwise. This process inevitably increases the degree of accountability by which key institutions and structures as well as governments can be made more accountable.

7. Unlike the MDGs, the SDGs are intended to be rooted in human rights principles and standards – this is a clear step forward. To date, the bulk of mainstream development policy and practice has failed to give adequate emphasis to challenging systemic patterns of discrimination and disadvantage (which amount to violations of rights) that keep many people in poverty.

8. The SDGs are more inclusive than previous frameworks – for example, they specifically refer to persons with disabilities; an additional 6 targets refer to people in vulnerable situations, while 7 targets are universal and 2 refer to non-discrimination. This emphasis on the ‘excluded’ in terms of inequality is a real strength in the SDGs.

In summary, proponents of the goals, like Columbia University economist Jeffrey Sachs, the UN Secretary-General’s special advisor on the MDGs, argue that they serve to mobilise support and resources, create pressure for political leaders to end extreme poverty, and create informed groups which create a global movement.

Related Quotes

- ‘The SDGs represent a great advance on the MDGs. The MDGs were largely determined by OECD countries and international donor agencies. In 2015 the SDGs have been produced by detailed international negotiations that have involved middle income and low-income countries. The SDGs are universal – they apply to all countries and actors. The SDGs are holistic – they cover poverty reduction and inequality, sustainability and economic growth with job creation. The SDGs are ambitious– they aim at eradicating multidimensional poverty and tackling inequality at the international and national levels.’

– David Hulme, Director, Global Development Institute, Manchester, UK

- ‘The SDGs themselves will do little. Local and international actors—governments, civil society and private sector–coming together around some of these challenging issues will be the opportunity to drive concrete progress. I know that the SDGs don’t put all of the important issues on the table, but they have made some rhetorical progress in some areas. In the area I work, access to justice, the SDGs mark one of the first times that the UN has acknowledged the fundamental links between justice and development.’

– Peter Chapman, Open Society Justice Initiative during discussion on Guardian Newspaper Global Development Professionals Network, September 24th, 2015

9 Key Arguments criticising the SDG agenda

1. The SDGs do not exist in a vacuum but rather in a world heavily characterised by systemic inequality, conflict, trade and tax injustice, corporate power, illicit resource transfers, corruption and weak or bad governance. The SDGs fail to adequately address yet alone tackle such issues (the structures and mechanisms that produce and reproduce inequality and poverty). This is a fatal flaw in the agenda and is one that undermines many of its intentions and goals. The SDGs must be placed in the international context of power and powerlessness.

2. Another core criticism of the SDG agenda is – the main strategy offered by the SDGs for eradicating poverty is more of the same – a ‘business as usual’ model with yet more growth. All the available evidence suggests that increased growth is unsustainable as we have now exceeded the planet’s ecological limits. At current levels of average global consumption, we’re already overshooting our planet’s bio-capacity by more than 50% per year. The available evidence indicates that we are blowing planetary boundaries at breakneck speed due, mostly to overconsumption in rich countries. This reality undermines one of the key pillars of the SDGs – more growth – this is simply no longer an option.

A related criticism is that the ‘growth-driven model’ assumes some form of ‘trickle down’ where wealth eventually ‘trickles down’ to the poor and lifts them out of poverty. Evidence indicates this simply does not work – since 1980, the global economy has grown by 380%, but the number of people living in poverty (measured as those on less than $5 a day) has increased by more than 1.1 billion.

3. A third line of criticism is that instead of encouraging poorer countries to develop strategies and policies to ‘catch up’ with richer countries, the strategy should be to encourage the latter to ‘catch down’ to the former. Some commentators argue that we should be taking a lead from societies where people live long and happy lives at relatively low levels of income and consumption not as basket cases that need to be developed towards western models, but as examples s of efficient living. They argue that we need to reorient ourselves toward a positive future, a sustainable form of progress, one geared toward quality instead of quantity.

4. A common line of criticism of the SDGs is that they are far too broad, with too many goals and far too many targets; if everything is a priority, then nothing is a priority. In a similar vein, some critics argue that some of the absolute targets such as ending malnutrition, malaria, and tuberculosis, are implausible, overly optimistic and inefficient (by diluting effort). It would be better, they argue to invest in 19 of the most cost-effective targets instead of all 169, this would produce better results.

5. Similar in tone and focus are those critics who insist that the definition of poverty and the targets set out are both inadequate and significantly dishonest. Defining poverty as living on less than $1.25 a day is wholly inadequate if other very basic needs are added. For example, the UN Conference on Trade and Development argues that the target should be $5 per day. Critics argue that the framers of the SDGs already know this but stick with the $1.25 measure because it’s the only one that get anywhere near the goal of eradicating poverty by 2030. Keeping the definition impossibly low will allow governments and international bodies to declare success just as with the MDG target on poverty.

6. From an environment and climate change perspective, the SDGs come in for considerable criticism primarily because there are no concrete mandatory greenhouse gas emissions-reducing goals in SDG 13 – Climate Action. These are seen as voluntary as is also the case with the Paris UN Climate Agreement. Mandatory cuts are seen by such critics as vital if hugely negative consequences are to be avoided.

7. From a human rights point of view a number of problems and criticisms emerge. First, the SDGs cover only a subset of internationally recognised human rights that remain widely unrealized amongst the world’s poorest. Secondly, the SDGs fail to analyse the root causes of the widespread and systematic poverty-related rights deficit and they ignore the structural reforms urgently needed nationally and internationally. There are also significant concerns among human rights activists around the measurement and monitoring of progress or otherwise (this is an issue in the context of the goals in general).

8. Many commentators argue that there is very significant tension and even contradiction between presenting visions, ambitions and goals in the language of rights while presenting them in the language of (development) goals. The latter tends to focus on trends and consequently finds that things have become better than they were. Critics argue that such comparisons are completely out of place when a rights perspective is applied as rights are not time or trend dependent.

9. Many critics argue that the goals are deeply flawed for one fundamental reason – the SDGs effectively shield the world’s most powerful organisations from any concrete responsibility for achieving the new goals, especially in the context of their wealth, power and impact – a prime example being transnational corporations. For many critics, it is the rich and powerful who contribute so much to creating and sustaining poverty, climate change and inequality and they must be held to account in terms of their impact on agendas such as the SDGs. They argue that postponing the roll-back of inequality to 2029 (SDG 10.1), one of the most important creators of poverty clearly illustrates the weakness of the SDGs politically.

Related Quotes

– William Easterley

- ‘Has anybody else noticed the SDG emperor has a shortage of clothes? Well, the Economist called the SDGs “worse than useless.” Another commentator described them as “a high-school wish list on how to save the world,” which seems unfair to high schoolers. Even Pope Francis warned in his address to the SDG summit this past Friday against the risk to just “rest content” with a “bureaucratic exercise of drawing up long lists of good proposals.’

– William Easterley

- ‘The SDGs are shot through with grand calls for private sector participation in making up the multi-trillion-dollar funding gap. Many have rightfully pointed out that this is a clear indication that privatization is on the agenda, which is very worrying indeed. But that aside, I find it interesting that the SDGs include NOT A SINGLE MECHANISM for corporate accountability. If we are going to have corporations running a ballooning development industry, shouldn’t they at least have principles by which they must abide? The SDGs are phenomenally silent on this issue. To me, this is profoundly dangerous.’

– Jason Hickel, LSE

- ‘So the other question I have is that we’re told (the big story of poverty) is that rich countries of the global north, through foreign aid programs and by participating in projects like the SDGs, are helping the less wealthy countries of the global south develop. But is this true?

If that’s the case, why is that right now, for every $1 that is given in foreign aid to the global south, around $18 is taken out by other means. Money leaves the poorest countries through rigged trade deals that benefit the most powerful countries and corporations, debt repayment on debts already paid off many times over, and massive tax evasion and other forms of corruption committed by political and business elites north and south, and helped along by the large and growing web of tax havens. So who’s actually developing who?

The SDGs don’t really have a lot to say about this dynamic, and in fact play a lot on the basic idea that it’s rich countries that are the generous ones. They do acknowledge problems with illicit finance in the global system but they talk about it vaguely, stating the need to “enhance global macroeconomic stability” through “policy coordination”. There are no specific responsibilities for anyone, or any actual targets.’

– Comments section contributor ‘IDO42992’ during discussion on Guardian Newspaper Global Development Professionals Network, September 24th, 2015

10 resources focused on the SDGs

1. Sustainable Development Goals: changing the world in 17 steps – interactive / The Guardian / despite being made in 2015, this still remains one of the best and most accessible overviews of the SDGs with useful links and related stories included at the end.

1. Sustainable Development Goals: changing the world in 17 steps – interactive / The Guardian / despite being made in 2015, this still remains one of the best and most accessible overviews of the SDGs with useful links and related stories included at the end.

2. The official Sustainable Development Goals Report for 2016 / UN Stats / it can be downloaded free and used in a variety of ways for research, projects and debates. It neatly summarises each of the 17 Goals and provides underlying data on each. It will be published annually and is worth consulting routinely for updates etc.

3. SDGs in Action app / Project Everyone / an SDGs app developed by over 800 mobile phone operators worldwide to highlight the SDGs – the world’s ‘to-do list’ on poverty, inequality and climate change. It is developed in partnership with Project Everyone (a non-profit global campaign which originated many of the videos above, their site contains many very usable films), the app includes 3 action options also.

3. SDGs in Action app / Project Everyone / an SDGs app developed by over 800 mobile phone operators worldwide to highlight the SDGs – the world’s ‘to-do list’ on poverty, inequality and climate change. It is developed in partnership with Project Everyone (a non-profit global campaign which originated many of the videos above, their site contains many very usable films), the app includes 3 action options also.

4. Global Rights, Nobel Goals: Refugees, Migration, the Sustainable Development Goals and Youth / a 2016 National Youth Council of Ireland resource on migration and the SDGs / has a useful introductory section on the Goals per se and how they might be approached pedagogically. Also has a section on Ireland the 2030 agenda.

5. Stand for Global Justice: International Development Priorities for the 32nd Dáil Eireann / Trócaire / an Irish perspective on the Goals from Trócaire, focused primarily on what the Dail (Irish Parliament) needs to consider as regards the SDGs and on what Ireland’s priorities should be. Very useful to generate a discussion on what small countries like Ireland could do.

5. Stand for Global Justice: International Development Priorities for the 32nd Dáil Eireann / Trócaire / an Irish perspective on the Goals from Trócaire, focused primarily on what the Dail (Irish Parliament) needs to consider as regards the SDGs and on what Ireland’s priorities should be. Very useful to generate a discussion on what small countries like Ireland could do.

6. Global Citizenship Guides / Oxfam / a set of 7 Global Citizenship Guides from Oxfam exploring an SDG related range of issues from different school subject perspectives including Maths, History, Arts and Geography. Lots of ideas and suggestions that can also be used outside the schools context. Downloadable free.

7. Social Watch coverage of the SDGs / one of our favourite Developing World sites, it contains a huge range of articles on the SDGs from diverse perspectives, many of them critical in nature. A good place to go to get alternative ideas and analysis.

8. Action for Sustainable Development / a major source of information and ideas on the SDG maintained by 4 international NGO coalitions / hard to access but worth the effort, it also includes a guide on how to interact with the official structures on the SDGs (of key interest to campaigners). See in particular the Shadow Reports by civil society groups on their government’s strategy and practice on the SDGs and the individual country reports – excellent for accessing Developing World views and analyses.

9. SDG Index and Dashboards Report 2017: Global Responsibilities / interactive online / while this looks like an inaccessible and very technical report (it is), it is nonetheless very useful particularly as it ‘scores’ each country on an SDG Index and includes a two-page profile of performance for each country (Ireland in on pages 102-103). Also offers many excellent and useful tables and graphics – a must data-wise. It is published by the Bertelsmann Stiftung and the Sustainable Development Solutions Network and can be downloaded (in different sections) free.

9. SDG Index and Dashboards Report 2017: Global Responsibilities / interactive online / while this looks like an inaccessible and very technical report (it is), it is nonetheless very useful particularly as it ‘scores’ each country on an SDG Index and includes a two-page profile of performance for each country (Ireland in on pages 102-103). Also offers many excellent and useful tables and graphics – a must data-wise. It is published by the Bertelsmann Stiftung and the Sustainable Development Solutions Network and can be downloaded (in different sections) free.

POSTERS: SDG Icons / 17 pictogram posters designed by artist and graphics designer Padraig Birch.

VIDEOS: See the blog on 5 videos on the Sustainable Development Goals worth a view (and a very useful TED Talk) from the Global Goals campaign so far.