Marjorie Laville-Pain of 80:20 interviewed Fr. Michael J. Kelly in Zambia for www.developmenteducation.ie. During the interview Michael talks to her about what motivates him to continue his work in the area – the motivation and dignity of those infected and affected by the pandemic.

He discusses how he believes the pandemic should be tackled in Zambia and outlines the responsibility of the whole country in dealing with the issues, pointing particularly to the media and the church. In the interview, he talks about why HIV/AIDS in Zambia and other developing countries has become ‘feminised’ and the additional challenges and burdens that it places on women. He considers the impact of the current financial crisis in the world and how it could provide opportunities for Zambia.

Throughout the interview, Michael shows how the “ABC” approach can actually work and promotes the function of “education, education, education” in all spheres as the most important component to tackling the pandemic; and dealing with the pandemic should be based on 4 pillars: learn to know, learn to do, learn to live together and learn to be. He also points to the potentials for cross- learning between Ireland and Zambia in light of new statistics outlining the increases of HIV transmission in Ireland.

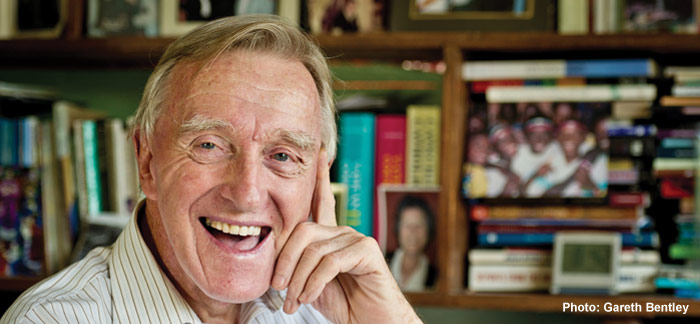

Michael Kelly was born in Tullamore, Ireland in 1929. After his ordination he moved to Zambia where he has lived and worked for more than 50 years and is a Zambian Citizen. Whilst in Zambia, he worked as a headmaster of Canisius College and completed his PhD studies in 1974 in the area of child and educational psychology. A year later, he became a senior lecturer and Dean of the School of Education in the University of Zambia (UNZA) and later became pro-vice- chancellor and deputy vice-chancellor of UNZA. In 1987, he became Professor of Education.

The emergence of HIV and AIDS in Africa, and the devastating impact of the virus on life in Africa and on close friends radically changed Michael’s life, directing him to dedicate his life to researching the impact of HIV/AIDS particularly the interconnection between HIV/AIDS and education. In 2001 he retired from UNZA to focus exclusively on his work in HIV/AIDS: “Observing the phenomenon, trying to reflect on and understand its significance and then act appropriately, has become a major preoccupation”.

He has been to the forefront of research in Zambia, other parts of Africa and the Caribbean, which has highlighted the critical role that education can play in the prevention of HIV/AIDS, and highlighted the many issues associated with the growing phenomenon of ‘AIDS Orphans’.

“What have I found that needs to be said about educating in an Africa afflicted with AIDS? My thoughts can be broadly placed under two rubrics. The first is that of understanding what education is called to be like in response to the pandemic. The second is to monitor how the pandemic has damaged the educational infrastructure of African societies and continues to do so”. (from the Introduction of Education: For an Africa without AIDS).

His research findings reveal that the availability and accessibility of education results in lower rates of HIV infection. Focusing on the situation of girls and women, Michael has publicised the term the “feminisation of HIV/AIDS,” revealing that women disproportionately suffer from the spread of the pandemic, not only by being infected themselves, but as having to also care for others who are infected in a variety of settings.

Fr. Michael has lectured and written extensively on the issues of HIV and AIDS throughout the world, he has been advisor to governments and international NGOs including Irish Aid, the Ministry of Education in Zambia and other African countries, the World Bank, UNESCO, UNICEF, DFID, OXFAM, etc. In 2006, Irish Aid initiated the first of the Professor Michael Kelly lecture series, which coincides each year with World AIDS Day.

- See https://fathermichaelkellyzambia.org for more information, podcasts of the lectures, powerpoint presentations.

The Interview

MLP: Fr. Michael, after 5 decades of working in Zambia, what inspires and motivates you to keep doing the work you do in relation to HIV and AIDS?

MJK: Good morning and thank you very much to yourself Marjorie and also to Toni and all the 80:20 people.

Two things keep me going all the time. First, is the wonder of the people who are infected or affected, especially the women. They are showing extraordinary courage in their remarkably dignified response to the epidemic. I know many people who have acknowledged that they are HIV-positive and each one of them, in different ways, inspires me through their patience, cheerfulness, absence of self-pity, and full acceptance of their condition. All of this is combined with a strong determination to do whatever is in their power to bring this epidemic to an end and to make it easier for others who also have to live with HIV. Seeing such courage, dignity and human concern, I feel that I too must share this determination to make whatever contribution I can to lowering the impacts of the epidemic and even to rolling it back altogether.

The second thing that keeps me going is a sense of urgency because of the size of this problem. One simple figure says it all for me. In Zambia in 2007, AIDS caused the deaths of approximately one person every five minutes of every day! You know, we don’t have much feeling for figures when we are told that 105,800 people died of AIDS-related causes in 2007. But if we turn this into smaller figures that we can cope with – the impact is different. The figure comes from the information that the Ministry of Health and the National AIDS Council in Zambia sent to the United Nations in January 2008 on Zambia’s progress in dealing with the epidemic: 105,800 people dying in 2007 means that there are 290 people dying every day…12 every hour (one child and eleven adults)…one every five minutes.

This is absolutely appalling and I don’t think our journalists, politicians or church leaders ever think of the epidemic in these terms. If these deaths occurred because of road accidents, we would all be up in arms. But because they are due to AIDS and are happening all the time in our families and communities, we just shrug our shoulders and accept that it is so. But I am sorry, I am just not able to accept that it is so. This is terribly wrong. This is not what God wants for us. And this can be stopped, but only if we work on it and do something about it. And that is what helps to keep me going, this sense of a terrible injustice being worked every day on our people and the need for all of us to do something urgently about it.

MLP: Are these figures coming from the report that came out recently from the Ministry of Health?

MJK: No, actually these figures, because I said they were from 2007, are based on what was presented by the Ministry of Health and the National AIDS Council to the UNGASS in January 2008. The recent report from the Ministry of Health is the Demographic and Health Survey, which does not cover the number of people dying.

MLP: What do you see as the three or four main priorities in relation to tackling this pandemic in Zambia?

MJK: Well the very first one I think we have touched on in some way – keeping it on top of the agenda. We can’t get complacent about it, we must all have a sense of urgency about it and I think that is one of our big priorities. The second priority is that while there are a big number of people dying, the number who die, will become less and less with the more widespread availability of antiretroviral therapy, and we are doing very well in Zambia in getting that to our people.

But of course the people must stay on it [ART], so the number of deaths I think will come down, but the number of people becoming infected remains almost the same as the number of people dying – just a tiny little bit lower. So we have to stop people becoming infected, therefore prevention must be a key priority, and with prevention I believe in the value and worth of the number of the interventions we are taking.

I think we are taking them [individuals who are HIV+] too late in the overall picture. What we are trying to do is to tell people to change their behaviour. We are not telling them to change the norms, attitudes and values that underline these behaviours – norms, values and attitudes that were laid down in childhood and that we have got to address and are not addressing, particularly the norms, values and attitudes relating to the status of women.

MLP: So, how would you suggest that we change this – through education? In what ways do you think we can actually begin to change these norms and behaviours?

MJK: Changing norms, values and attitudes is a long-term process, it’s not something that’s going to happen overnight. Yes, through education, but by education I don’t mean just school education in this context. I mean education at all levels; education through the media, particularly because they have a great deal of influence. The media should be portraying that in Zambia we will no longer accept sexual activity outside of marriage in a man – which is currently condoned in a man, but is condemned in a woman. Equal treatment for men and women – but that treatment requires them to remain faithful to one another. But we are not pushing on that, we are saying ‘Oh yes there should be greater fidelity’ but we are going back to that basic concept which says ‘ah well he is a man and you can understand it in a man’. We have got to root that one out and I think we can only do that through education: education in the family, education in the school, education through the media, education through the church. I do not think the church is doing enough to lead in this area.

MLP: I am glad that you have actually brought up the subject of the church, because I believe the church itself in Zambia has a very big influence. I think that through church a lot of messages could be passed to the people of Zambia?

MJK: Oh yes, I am absolutely certain of that. Many messages can be passed on and they have got to be passed on, the church leaders and the traditional leaders who form what we call the ‘gate keepers of society’ – the gate keepers to traditions, to beliefs and understandings of what is accepted. And they have got to be used to communicate these kinds of messages.

But now it’s no good for the church leaders to just say, ‘you should be abstinent’ or ‘you should remain faithful’. With this kind of messaging how does one bring this about if you have got norms and things in the society which are not supportive?

However, let me give you a certain amount of encouraging news.You mentioned the report from the Ministry of Health that was launched last Thursday, the Demographic and Health Survey, it is a heavy document but, with a great deal of information in it.Now there is one very encouraging piece more than one! encouraging piece of information in it – ‘young people who are not having sex aged 15-19’ – the portion who say that they have never had sex has gone up to 60%, it was 55% the last time this survey was done about four or five years ago. Now that’s a huge increase, it is a very, very large increase, because it takes time again to change that kind of an attitude.So young people are not having sex until much later or they are not having as much sex as they used to in the past, and that’s one way that we are going to be able to cope with this. But this is one of the changes you see which is coming slowly – slowly through education. One of my beliefs, but I won’t be alive to be able to confirm this, is the impact of education. I am talking even more than formal school education on this epidemic, that will not be felt so much by the kids who are going to school now, but through their children when these kids become parents themselves, they will communicate the messages, just as a girl who has been to school shows much better concern for the health of her children than a girl who has not been through school.

MLP: Now let’s get on to the current financial crisis in the world. How do you see the current financial crisis impacting on the fight against this pandemic?

MJK: Well, bad … and good! It’s easier to take the negative side first. There will continue to be anxiety about the continued availability of antiretroviral drugs. This has been a worry, even without the financial crisis. Who is going to pay for these drugs year after year, because a person who begins on these drugs must continue the treatment for a long time, so that is one aspect where there is reason for worry. More money has got to go into prevention activities – but will more money be available? We have had guarantees and assurances from the international community that they are going to protect this money, that they are going to reinvest it, that it will remain available, and we hope that they will be able to do so.

It’s a crisis, but every crisis has opportunity. So opportunities are here. One opportunity is for Zambia to put their own resources into dealing with this – we can’t be relying forever and ever on outside resources to deal with this problem – this is our problem and we must deal with it more and more. I hear increasing calls that there should be more Zambian resources going into this.

And I think we should bear in mind that when antiretroviral drugs became more universally available a couple of years ago, our first move to expand them was financed entirely by Zambian resources – without PEPFAR, without Global Fund money. Before these became available, before they flowed in, Zambian money was there, and Zambian money bought the drugs and made them available to the people. We had the resources then. Okay we are caught also in the financial crisis, but if the health of our people is what counts, then we should be giving more to health and maybe this would push us more into dedicating more of our resources to health and education.

There is another move that is going on at National AIDS Council, and a few other areas I think are collaborating in this, and this is to put aside local resources (and have a means of collecting local resources) to deal with this issue and to have a local trust fund to deal with this. Zimbabwe, despite all of its problems, over the years has had a tax – a fairly heavy tax – on petrol, and that was put by exclusively for HIV and AIDS and they did, in spite of their problems, use that money for that purpose. I think we can learn a great lesson from our sisters and brothers down there.

MLP: I know that you have said that the percentage of young people NOT having sex have risen according to that Demographic and Health Survey from 2002 to 2007. What do you have to say to young people in relation to this pandemic?

MJK: We hear a great deal about the “ABC” approach and some people say that’s unrealistic, but I say it’s not.

First of all “A”: I am not talking just about abstaining from sex, that’s just one of our problems – look at all the other problems we have. I say to young people Abstain from Corruption , Abstain from substance abuse , especially from drunkenness and alcohol that will lead you into activities which will encourage the transmission of HIV. Abstain from degrading the environment and protect our environment.So, to abstain should not be seen too narrowly as just abstaining from sex in order to prevent HIV.

Then the “B”: Be faithful. Yes, be faithful to yourself. As a person, be your own person, stand up for yourself, be responsible for yourself, be responsible in everything. That’s the second message that I would give to young people.

The third one “C”: would be to try and understand what is the meaning and the value in all sexual activity. That it is an issue of relationship and that there is no such thing as casual sex – that it is a wonderful thing, a wonderful gift that has been given to humanity and to individuals by God. It is so wonderful, that we have to protect it and we protect it by refusing to use it until we are in a stable union of marriage. And it’s meant to bring two of you together to keep you in union together and give you great happiness and joy during life and that it’s worth waiting a little bit for.

Is it unrealistic to say Abstain? Yes, it is a very high ideal. But remember, if you do not have high ideals you get nowhere. The great Martin Luther King had wonderfully high ideals, but he never had the ideal, I do not think he had, that one day one of his people would be the President of United States, and there it is now, because he had high ideals and put it before the people. And it takes time. Similarly, with Abstinence and Fidelity, these are high ideals, but they are really worthwhile and they will lead to really wonderful happiness and accomplishment and achievement.

MLP: Thank you. Since Irish Aid is here in Zambia and has been for a long time, what do you see as a potential role of the Irish people in relation to HIV and AIDS?

MJK: Yes, that’s a very difficult question. Maybe that Irish Aid should continue supporting some of the areas that it is supporting already; trying to alleviate the impact of the pandemic through its support to orphans and also that it is involved in joint committees. But Irish Aid along with the Netherlands is the lead agency [in Zambia] in education and through education, a great deal can be accomplished here. There is more and more proof coming out that actual formal education – school education for as long as possible is actually helping people. It did not in the past, but it is now. Things have changed in the last ten years and therefore it is a big help for Irish Aid and the Irish people to continue to support the development of education here. But then within education itself that there should be stronger or more organised focus on dealing with HIV/AIDS. But thinking of it the other ways also, twice in the last three weeks I have read about HIV increasing in Ireland. Only yesterday I read about increases in Kerry and in Cork, they are not huge numbers, nothing like the numbers we have here but still substantial numbers and everyone is an individual, lets never forget that and these are not immigrants, these are local people for the most part and for the most part apparently, it is through ordinary heterosexual transmission that its occurring. Ireland will be looking for assistance and support, so what can the Irish people learn form Zambia? Let this be a two way process that we are learning from one another and supporting one another in confronting and dealing with this issue.

MLP: I know we have been talking about education throughout this interview, but I have a question here that asks what the role of education is in all this. I am not sure whether you have actually answered it directly?

MJK: Well first of all, to go backwards a little bit and to something I said years ago, that I have heard other people saying…

When Tony Blair was going up for leading the Labour party in the English general election for the first time back in the mid-90s, he was asked what were his policies and he replied that he had three policies: the first one is Education, the second one is Education and the third one is Education – and that is the policy I believe for dealing with HIV and AIDS.

Education, Education, and Education. More and more it’s in schools that young people’s values and attitudes can be formed, its in schools that you can transform young people from the kind of predatory male attitude that we tend to have, into a much more equalising society. It is in school that you can learn a great deal about not having stigmatising attitudes, and stigma is very much at the root of this problem.

UNESCO back in 1996 published a document on education for the 21st century and it proposed that education for the 21st century should be based on 4 pillars – now these were not because of HIV and AIDS, these were in general, but I am applying them now to AIDS:

Learn to know. In the schools we must learn to know all the facts. It’s very shocking in Zambia that about only 33% I think, have good comprehensive knowledge [about HIV and AIDS], everybody has heard about HIV and AIDS, but about 33% knows ‘certain’ things, know some of the myths, know how to deal with people and know how to protect themselves against infections. So knowledge is still required, that is the first pillar – Learn to know.

The second pillar, Learn to do. We need certain skills and therefore in schools, we can learn certain skills: the skills of self assertion, the skills of making up your mind, the skill of being responsible, the skill of being able to walk away from a situation and not get involved – Learn to do.

Third, learn to live together: where boy and girl can live together; Bemba and Tonga can live together; HIV infected and non infected can live together. Remember, because of the availability of drugs, there will be more and more children in school who have HIV than there ever were in the past, so the third pillar – Learn to live together, and the education system can be built on that [pillar].

And the fourth one is Learn to Be: Be your own person, be responsible, stand on your own feet, learn to be independent – that independence is required in all areas of life, but in this area, it is also very, very important.

So that’s what I feel that education can do. The evidence we have coming out and I believe more of it is coming out in July of this year through UNESCO from the State University of Pennsylvania, is that education of younger people from the 15 to 24 age group are the ones who have had more education and are much less likely to have HIV – so, Education, Education and Education.

MLP: Thank you, very interesting. Fr. Kelly, you were here in Zambia before this pandemic started. Can you explain what it was like before? Have people’s attitudes changed? Because when it was happening, no one really knew what was going on? And then when there was a time when people were dying, how was it then compared to now? Do you feel that people have gotten used to this and are no longer caring? What do you think?

MJK: Oh yes, there was a lot of fear I think in the beginning and the fear was negative in this sense, it did not help people very strongly to change their behaviour. But it made them afraid of the people who were infected. And it also made them judgemental of the people who were infected. If you became infected, it was your own fault, you were foolish, and you behaved foolishly. And therefore, why should we be giving them certain treatment or understanding or whatever it may be, because it was their own responsibility.

We still say people are responsible ultimately for their actions, but we have a much better view now of the whole background and environmental situation of people, that they are not always able to take actions completely freely. There was a lot of stigma therefore attached to it in the beginning and a lot of fear about it and I do not think that that’s gone away entirely.

You say that the people were dying, yes they were dying in very large numbers, but as I pointed out at the beginning, they are still dying in very, very large numbers. But there was a sense of hopelessness in the beginning, it was a death sentence and therefore nobody wanted to mention it or anything like that. It’s no longer a death sentence, but some people still will not take the steps necessary to deal with it.

And one of the sad things is, and this relates to the status of women, that many pregnant women who are infected and who could get treatment that will protect them so that they would live and protect their unborn infant so that it won’t contract the disease, are not taking the medicines even if they know their status because they are afraid of the reactions of their partner. That their husband will beat them or will throw them out of the house or even in some cases, if they are on drugs, steal their drugs. He will refuse himself to go for a test, but maybe he is aware that he is HIV positive or could well be, so he will share his wife’s medications and therefore the problem remains – this is one I think that we have got to overcome.

There is almost no reason now why a child should be born with HIV or become HIV positive through breast-feeding if the children take the drugs and if the mother is also taking the drugs, but it is the attitudes of men that is tending still to stop that. Now some of that may be only in the women’s heads, that they are afraid and the men might not say it, but in many cases the men will say it and there is a lot of evidence that men are oppressing women in this kind of a way. That is something that is still there with us. So we still have the deaths and we could stop these through changes in our attitudes and our approaches to people but the stigma that began in the beginning is still with us very, very strongly and that is one that we have got to try to continue to overcome.

MLP: Thank you Father Kelly. As you can imagine I have loads and loads of questions, but of course time does not allow me to sit here with you and discuss all this. But women in Africa and women in Zambia are the pillars, as we all know, so how do HIV and AIDS directly affect women and what implication does this have for the future? This will be my last question I am afraid.

MJK: Well the situation with women is very, very tragic. We use the word ‘feminisation’ of HIV and AIDS – that it is becoming a woman’s disease, here in Africa, not so much in other parts of the world, but in Africa, because it is heterosexual [transmission]. In other parts of the world it’s through homosexual transmission or through drug injections and also heterosexual transmission, but here in Zambia and many other [developing] countries, for every 40 men there are 60 women infected or even a little higher that 60. It’s a women’s disease to that extent.

Looking at it from another perspective, that’s almost an advantage, because women go to the doctors much more easily than men go to doctors and so we have more women being treated than men – many more. So that’s a positive aspect, but of course a positive aspect to something that’s already very negative. But if women are infected and not getting the treatment, of course this means that these women will die at a much younger age than they should die and therefore children are being left orphaned or in the care of grandparents who find it very difficult to deal with them, that’s one of the negative aspects.

Another negative aspect for a woman who is infected is that she has to continue to look after a household, notwithstanding her infection, and she has to produce the crops, generate the income in order to be sure that she can put a meal on the table.This compromises her position very much, bearing in mind that most of the food in these subsistence households is produced by women and as they get weaker through having the virus they are not able to do as much work as they used to be able to do. Also, they are affected if it becomes known that have the virus and they are selling tomatoes or something at the side of the road, people won’t buy from her, people stop buying from anybody they think are infected. That’s a sign of stigma of course, people say they wouldn’t but they don’t like buying from them.

The women are also subject to violence, gender based violence of all forms, and the children also. And it is through violence that [the virus] is transmitted, violence not only outside marriage, but violence within marriage, and one of the things which is absolutely necessary I think in Zambia is to make violence within marriage a crime – a criminal offence. In Marital Rape -the possibility of women getting antiretroviral drugs very quickly, what we call Post Exposure of Prophylaxis – PEP – is difficult to access because these kinds of rape cases [tend to occur] at weekends when clinics are not open or not available. So what does a woman do who was raped on a Saturday or a Friday night? First, she has to go to the police then the police have to get her to a clinic – two big hassles there. Often it is the person who is the victim that is blamed – that is not new to Zambia, and it is not new in the world. There is a legal phrase from the 17th century about three hundred years back saying it is the victim who is on trial and not the assailant. So this is a long-standing human problem that we have to deal with.

Try to look at the positive side, it is terrible but it is forcing us to deal with these human problems, these long-standing human problem in that particular case, the long-standing human problem of the subordination of women that they are second class citizens, so we are being forced to deal with these because of HIV and AIDS.

So with women, first of all I think a tremendous tribute to them, the way they are standing up to this, because they are the ones that are dealing with it, they are the ones that are coping with it and the problem will be controlled, it will be conquered, but it will only because of women.

The men will follow the women, and the women will take this in charge. You mentioned the number dying and in some extent, this triggered a lot of community action in Uganda, the women said ‘We are tired seeing our children being buried, our friends, our relatives being buried, we are going to stop this disease’ and so they stop by refusing to have sex with their husbands. In Uganda they called this ‘Zero Grazing’ and is becoming more and more popular amongst communities. I believe we will have the same here.

MLP: Father Kelly, I would like to thank you very much for this interview.

MJK: Thank you very much Marjorie and I wish 80:20 every success in the great work that they are doing and continuing to do and may that work expand and bring about fruits not just in this area but everything that will make the life of young people much better.