Photo: © Sandra Jasmin Nieuwenhuijen/Photographers Without Borders/ Hands for Hope, October 2018

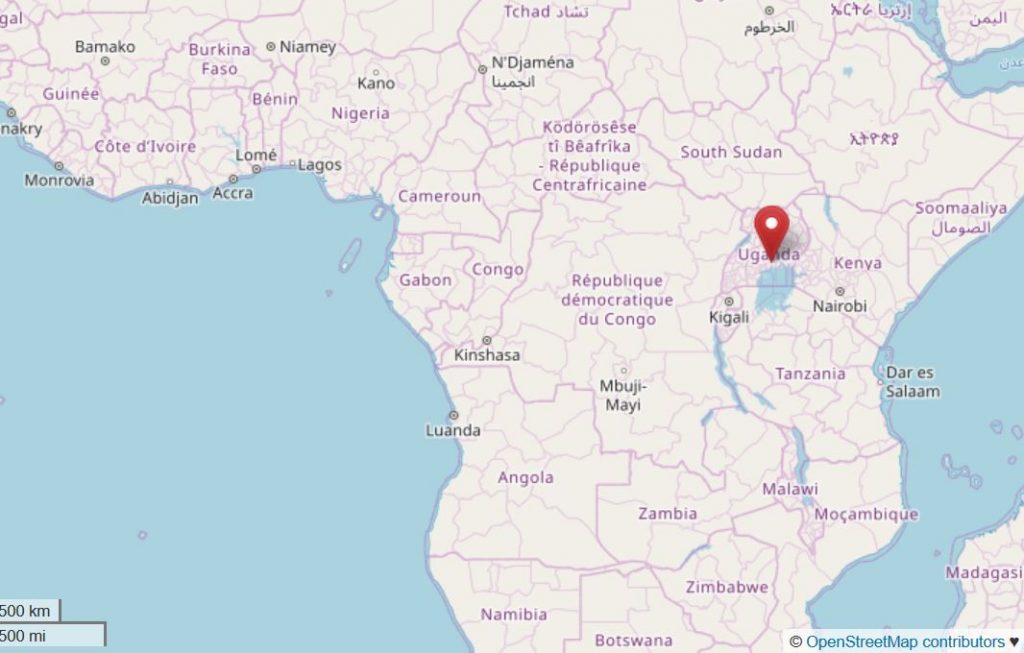

In the second part of the Living Between Trains and Drains series, we explore the daily struggles and global realities of informal settlement living, with a focus on life in Namuwongo ‘slum’ in the city of Kampala in Uganda.

Uganda, situated in East Africa, has a population of 42 million people as of 2018, according to the UNDP. Significant in this population statistic is Uganda’s age profile – nearly half (48.47 percent) of Uganda’s population is under 14 years of age.

In terms of its human development progress as it relates to poverty, the World Bank reports that:

Uganda surpassed the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) target 1a of halving poverty by 2015, and made significant progress in reducing the proportion of the population that suffers from hunger, as well as in promoting gender equality and empowering women” (Uganda country overview, WorldBank, updated March 25, 2019)

However, despite these gains and Uganda’s recovering economy since 2017, the realities of poverty remain volatile. According to the World Bank, more than a third of Uganda’s population is still living below the extreme poverty line of $1.90 per day and the country’s vulnerability to poverty remains heightened “…for every three Ugandans who get out of poverty, two fall back in”.

Some 23 percent of Uganda’s population are based in urban areas. This is expected to increase from nearly 6 million people (2013) to more than 20 million by 2040. The World Bank’s 5th Uganda Economic Update report published in 2015, “The Growth Challenge: Can Ugandan Cities get to Work?” focuses on some of the issues of urbanisation facing Uganda:

- Currently, 6.4 million Ugandans live in urban areas, with some 69 percent of the population located in small cities (500,000 people)

- At current future growth rates by 2040, more than 21 million people are expected to reside in urban areas

- Uganda’s capital city Kampala is home to 31 percent of Uganda’s urban population. There are 57 slum settlements in the city which are spread across the 5 divisions of Kampala – Central, Kawempe, Nakawa, Lubaga and Makindye. Central region has the highest number of people living in urban areas (54 percent)

- In the last decade, the number of people living in Uganda’s urban areas has been increasing by an average of 300,000 people per year. If current patterns of growth continue, Kampala will become a mega-city with a population of more than 10 million people within the next 20 years. Similarly, the population of other towns will increase exponentially

- 70 percent of non-agricultural GDP in Uganda is generated in urban areas

- As with other rural-migration patterns in developing countries, the anticipated opportunities for work, higher incomes, better living conditions, access to services, etc., in urban areas, particularly big cities continue to entice Ugandans from the rural areas

- Between 2000-2010, cities in Uganda accounted for 36 percent of overall job growth

- Yet, despite the perceptions of employment, there are high rates of urban unemployment and underemployment, with the rate of creation of productive jobs being lower than the rate of growth of the urban population. Many of the unemployed are the youth (18 to 30 years of age)

- With increasing urban migration and the slow pace of infrastructural planning and responses, the congestion and overcrowding in cities across Uganda restricts the movement of goods and people along with the supply and quality of housing, along with the challenges of social and environmental services. By 2013, some 38 percent of the urban population was connected to the electricity grid

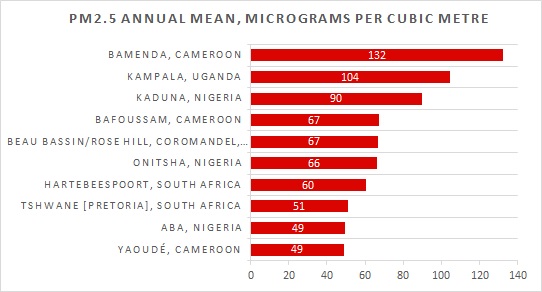

- Kampala is the second most polluted city in Africa (when taking into consideration PM2.5 – that’s the considered ‘dangerous’ fine particles of pollution such as dust for example). With a PM 2.5 of 140, Kampala is 21st on the global listing

- With walking still the main mode of transport in Kampala – 70 percent of the residents walk to work – the implications for the cities future environmental impact is enormous!

Ten Worst Polluted Cities in Africa

As noted previously, urban migration has necessary economic advantages. The rate of technological progression and the demand for labour in urban areas continues to fuel the push towards urban migration. With planning, logistical and infrastructural needs lagging behind the rate of urban expansion, the reality is that individuals and families who migrate to the cities in search of work are finding that the only available accommodation is located within the growing number of informal settlements scattered throughout the cities.

Namawongo ‘slum’ in Kampala, Uganda is one such experience. While policy makers, aid agencies and non-governmental organisations continue to highlight, bemoan and theorise the rapid rural-urban migration phenomenon in Uganda, along with attempts to address and plan for the wider associated infrastructural challenges, the day-to-day lives for the majority who reside in these communities continues.

Insight into Namuwongo ‘slum’

Makindye Division, one of the five administrative zones that comprise Kampala is situated on one of the 7 hills which make up the city of Kampala, referred to as the ‘Beverly Hills of Kampala.’ Namuwongo is located in Makindye district. Built on a swamp area, Namuwongo is 6 kilometres to the southeast of Kampala’s central business district and in close proximity to some of the more affluent residential areas such as Kololo and the upcoming Bugolobi.

Namuwongo has the 2nd largest ‘slum’ area in Kampala, with some 15,000 ‘official’ residents, although some estimate that this figure can be as high as 30,000.

Namuwongo’s rapidly expanding settlement has spread across to the railroad tracks and is home to what is locally known as ‘Soweto slum’ and is claimed to be the second largest slum in Uganda. While total population figures vary between 15-30,000 residents and higher if you consider unofficial figures, the increase in the number of ‘official’ structures built is an indication of the rate of growth of the settlement. In 1993 there were reportedly 451 ‘structures’, which increased to 2,554 by 2016.

Much of what you read about Namuwongo highlights the overcrowded and unsanitary living conditions that many ‘slum dwellers’ face, as described by Henry Lubega in his article in the Uganda newspaper, Daily Monitor:

Less than 10 metres from the railway line to Port Bell [a road in the industrial area] is a labyrinth of structures of mud and wattle, unbaked bricks and in some cases well-structured houses. Most of them a block of single rooms. These structures are sandwiched between the railway line and the channel that takes Kampala’s sewerage to Lake Victoria. The channel border line torments the residents of Soweto not just with the stench during the dry season but also with floods whenever it rains. Like many slums, the houses there are not planned and access is through a maze of footpaths between buildings less than a metre apart. Some of the paths also double as trenches and dumping areas. Unfortunately, they are also a children’s play area”.

As an informal settlement, Namuwongo residents are consistently at risk of removal and their homes demolished, as photographer Joel Ongwec outlines:

Namuwongo therefore became a temporary base for everyone who lived there: people not sure if they would be able to spend the next night in Namuwongo, even though most of the people work in the city including for the municipality, or on construction sites, road sweeping, restaurants, hotels, security, and so on. These positions might sound low or irrelevant but they are vital to the functioning of the city and without them there would be no urban development”.

(Africa at LSE exhibition – Namuwongo: Key to Kampala’s Present and Future Development)

Meeting basic needs without safety nets

Added to these uncertainties are the rising cost of rents in Namuwongo slum. A small single room made from mud and ‘wattle’ and without electricity could cost between 30-60,000 Ugandan Shillings (UGX) per month (€7-14). For those looking to rent rooms with electricity this significantly increases to between 90,000 UGX and 400,000 UGX (€20-90). However, while €6 or even €90 seems a good deal when compared to a city like Dublin where average rents are €1,875 per month, remember that many residents in Namuwongo earn much less than the World Bank estimate of $1.90 (€1.66) per day. Some residents don’t earn this amount in a week, as you’ll see from the two stories of Namuwongo residents Richard and Lizzie, outlined in the next section of this series.

Even those with jobs do not earn enough to meet their basic needs. For example, a police officer with the Uganda Police Force is claimed to earn UGX385,279 (€90) per month. A primary school teacher in a local government school in Uganda earns an average of UGX250,000 (€59) a month, and a secondary school teacher could earn up to 450,000 shillings a month (€105). Not all officers or teachers may receive the official salary amount and oftentimes their salary is delayed for months:

Daphine Mirembe, a teacher at one of the famous primary schools in Kampala gets Shs 300,000 [€70] in salary, with an increment of either Shs 20,000 or Shs 25,000 [€4.70-5.86] at the beginning of the year depending on either excellent work or sheer luck…’We have not received our salary for February and the worst month is January when salaries come in the middle of February” (The Observer, Uganda).

Employment opportunities for the majority of Namuwongo residents are limited. Some work as security guards for the private sector and can earn on average around 120,000 shillings per month (€30) for a 6-day, 12-hour shift. The majority, as you’ll see below, have unregulated and uncertain incomes. One woman for example, living in Namuwongo talked to developmenteducation.ie of earning 1,000 shillings (23 cent) a week by washing clothes.

These earnings are used to pay for rent, school fees/books/uniform, basic essentials such as food, energy (for cooking, light, etc.), clothing, medical care, etc.

There are no government safety nets.

Documentary: Powering Namuwongo

A documentary featured at the 2016 Uganda Documentary Film Festival produced by Joel Ongwech, while focusing on energy needs and consumption, demonstrates some of the difficulties that residents of Namuwongo face daily in their struggle to survive.

(Note €1=4,256.68 shillings).

What do the residents say? Findings from a household survey

Out of 10 ‘slums’ surveyed in Kampala in 2010 as part of the Kampala Basic Needs Basket survey conducted by the John Paul II Justice and Peace Centre, Namuwongo was reported to have the highest incidence of absolute poverty with 90 percent of the households interviewed found to be living below the absolute poverty line. The survey also found:

- Almost 40 percent lived on less than a dollar a day, with 98 percent of those being women. A large proportion of household heads in the Namuwongo community are women, with female-headed households comprising 21 percent of the families surveyed in 2010.

- All the female-headed households interviewed were well below the absolute poverty line. Women are especially vulnerable: of the more than 10 percent of people who have never had formal education, almost 95 percent were women.

- Additionally, 98.7 percent of the 38 percent of respondents who reported being unemployed were women. Women are traditionally more vulnerable to unemployment due to barriers to access, limitations on movement and lack of support for childcare during work hours.

Despite the widely documented challenges of everyday ‘slum’ living, life in Namuwongo is vibrant. It is a thriving settlement packed with a variety of business opportunities including carpentry, restaurants, bars, food stalls, retail shops, mechanics, butchers, etc. These enterprises flourish in the evenings as the population of workers return home or finish up their work.

In the next part of the Living Between Trains and Drains series, we explore the daily lives of two residents of Namuwongo ‘slum’. Richard and Lizzie share a rare exposure of the daily realities and struggles for those living in informal urban settlements with social workers in Kampala who are challenged to respond to these needs.

The Living Between Trains and Drains series explores the day-to-day realities of high density urban living with a focus on the city of Kampala, Uganda