GOAL and Bridge21 collaborated on a three-day workshop, held in Bridge21’s purpose-designed learning space in Trinity College, Dublin. The workshop utilised the Bridge21 learning model.

Learning in this model is team-based, technology-mediated, project-based and cross-curricular (see case study section for more detail on the model). The model was employed to explore the global issues of interest to the student participants, and overarching themes including poverty, inequality and interdependence. During the workshop students created digital artifacts (slideshows, videos, radio programmes) which were used to further the learning among the creators and their peers.

The three big ideas of the activity were:

- to examine global issues of interest to the students and conduct primary and secondary research in order to produce outputs (a slideshow, video and radio show)

- to develop critical thinking skills by considering issues from multiple perspectives and challenging stereotypes

- to relate new learning to overarching ideas such a inequality, poverty and interdependence

Participants

Participants that took part included 24 Transition Year students from a number of different Dublin schools: Drimnagh Castle, Moyle Park, Donabate Community College, Westland Row CBS, Coláiste Bríde, Mount Temple Comprehensive and Mercy Secondary School.

Timeframe

The workshop took place over three days (approx. 15 hrs in total) in March 2015.

Materials

Learning space

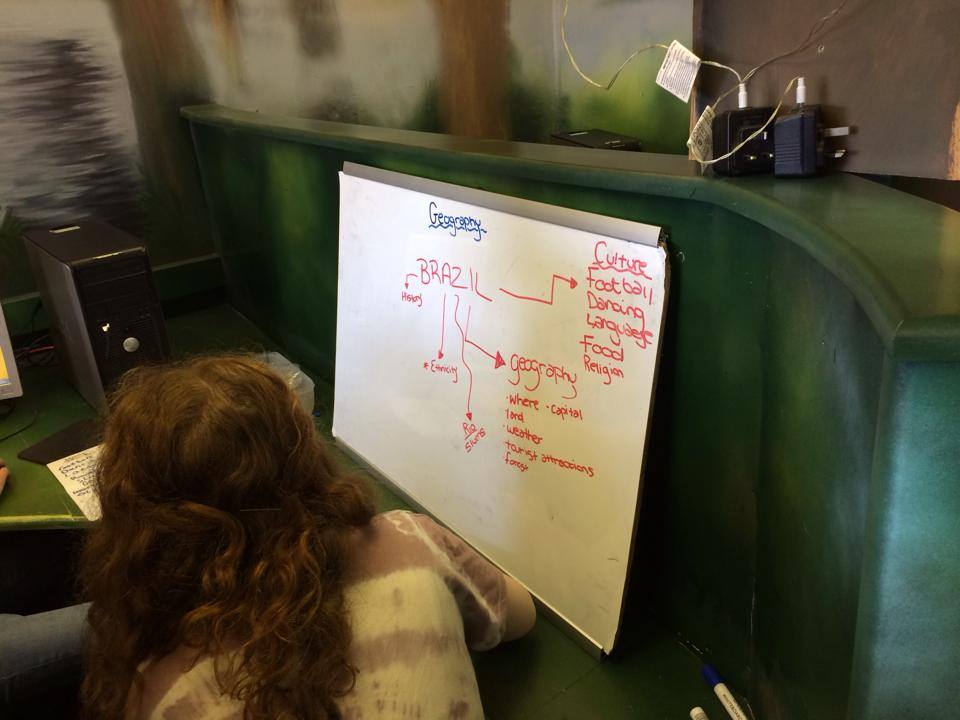

As team work was essential to the workshop, the space used was designed in pods where students could work collaboratively. Each pod contained two PCs. There was also a separate space where the whole group could be gathered for presentations, discussions and so on.

Technology

The PCs in the pods had basic software programmes installed. Groups used Google Slides to make presentations, Windows Movie Maker to make videos and Audacity to make their radio shows. Groups also made use of digital cameras (that allowed short video clips to be recorded) and audio recording devices.

Workshop materials

Other workshop materials included whiteboards, whiteboard markers, post its, pens and worksheets and materials related to specific tasks.

Work process

The learning experience was organised over a three-day period. The activities of each day are detailed below.

Day one

- Students explored the concept of the global south through games and fun activities, for example a global south guess who game, an A-Z countries listing activity and so on.

- In teams (of four), students picked a country from the global south that they had identified in an earlier activity. This became their focal point for the day to allow for deeper and more focused engagement. They did a comparison activity whereby key facts and statistics from their countries (e.g. median age, life expectancy, literacy rate, etc.) were compared with the countries selected by other groups. Students were expected to analyse the differences and a discussion teased out some key issues and themes – e.g. critical thinking about data.

- Students then created slideshows about their chosen country. The students were required to cite their sources of information (e.g. https://hdr.undp.org/en/countries) to get them used to looking up reliable sources of data. Each team presented and discussed their slideshow. Issues around stereotypes and images and messaging were particularly focused on at this time.

Day two

- Day two started with a global trade game. Teams were each given a different country and had to trade resources and tools to create wealth. The aim of the game was to generate as much wealth as possible within an unspecified amount of time. Complications and new opportunities to generate wealth were added during the course of the game. At the end of the game, there was a rich discussion about global inequality, trade, debt and so on.

- Students then drew on their work so far to brainstorm global issues. Each team selected an issue of interest to them and produced a video about that issue. The video needed to contain the following elements: a definition of the issue, contextual information, a quote, a graph and photographs. Each team presented and discussed their videos. Issues selected ranged from dysentery to fair trade to child soldiers.

Day three

- On day three, teams created a radio show on their chosen issue. Radio shows needed to contain original research done by the teams with the general public, e.g. vox pops or survey results. Students were also encouraged to link the issue to Ireland, or to a bigger agenda, e.g. overseas aid and development.

- A discussion was had following the team presentation of their radio shows and some concluding activities were engaged in.

Case study: Bridge21 – a new model for learning

The main elements of the Bridge21 model of learning added to the Development Education experience in interesting and in some cases, unexpected ways:

Team work supported by mentors – Bridge21 employs a structured team-based pedagogy influenced by the Patrol System learning methodology used by the World Organisation of the Scout Movement.

- As part of the team forming process, each team had to pick a name connected to the global south and appoint a team leader. They then worked together on the various tasks.

- Students reflected positively on the use of teams following the workshop. Their comments pertained to the idea of using their different skills and talents to work together to do something which otherwise wouldn’t have been possible, or as good in terms of what they took from it.

- The mentors assisted the teams, mainly around technology (using software such as Audacity, Windows Movie Maker, etc.). Additionally the mentors helped to challenge teams in their thinking and process but never led or interfered in the project outputs. The students work was their own at all times.

Technology-mediated learning – The Bridge21 model calls for a constructivist use of technology. Teams needed to use the technology to research and complete their assigned projects.

- As the internet was used for accessing information about the countries and issues the students selected to focus on, they needed to scan and filter content and decide themselves whether it was useful and reliable.

- The use of the internet as the primary source of information on topics was beneficial as it helped students get different perspectives on their topics. Had information been given out by the facilitators this opportunity may have been missed and the activities would likely have been more constrained.

Project-led – The tasks assigned to the groups to work on required action within a limited timeframe. They required the students to work together as a team in order to create a successful output. The projects also allowed for the development of skills (e.g. information retrieval/research, written and oral communication, technical skills, etc.) while simultaneously allowing students to acquire knowledge about issues of interest to them. Project outputs (the slideshow, video and radio show) and associated presentation of same provided useful hooks for fruitful discussions.

Cross-curricular – The cross curricular nature of the workshops meant that students could be creative, not constrained by one particular subject or lens. They were free to engage with and present content in creative ways, for example by integrating visual arts or drama, connecting with maths, geography and so on.

Project Learning

What worked well?

- The games used, especially the world trade game, allowed the students to have fun, while also learning about serious issues. They also provided a hook for interesting discussions.

- The use of whole class discussions after a shared learning experience was useful. Students said that they liked hearing the view of their peers.

- The sequencing of activities worked well. When planning a three-day workshop we were very conscious of not making it too difficult. The students needed to learn about serious issues in a fun and engaging way. Breaking up the activities the way we did seemed to create a nice balance.

- Giving students time to mingle informally worked well. Oftentimes their discussions naturally involved the issues they were looking at. For example, a group of students were overheard chatting at lunch about Fairtrade products and their own shopping habits.

Some challenges

- Given that there were lots of games, it was a challenge to keep the project outputs serious

- Some groups liked to include funny/jokey sections. That was permitted during day one (groups who chose to include something like that were not forced to remove it) but after the world trade game on day two we (the facilitators and mentors) tried to create a more serious atmosphere. The video task also had a lot to it which meant students were too busy to add extra jokey elements in.

- We were fortunate that we had the Bridge21 learning space, three full days, and the mentors on hand. It would be more difficult to do this in a school where timetabling issues may pose an issue.

Tips and pointers

- Give students a choice in what issues they look at. Students said they appreciated this and it made them take the tasks more seriously.

- Aim to have mixed ability groups, cognisant of the different skill sets required for the tasks you have planned.

- Don’t leave the tasks too open-ended as students may not know what is required. By getting them to include quotes, graphs, photographs, etc. in their videos the quality of the research students had to do was improved, as were the outputs. A previous pilot was more open-ended and the outputs weren’t as good.

- Don’t judge the quality of the learning by the outputs. It’s the process that’s important.

- Remember to be human – these are difficult topics. It’s ok not to know all the answers or not knowing what to say when students get upset by an issue.

Measuring Impact

According to a recent research report produced by DEEEP (2011), typical impacts arising from Development Education occur at three levels: personal transformation, education systems transformation and community/societal transformation. This workshop sought to measure transformations at the first two levels.

At the end of the three-day engagement, students were asked to do a written reflection on what would stick with them most. A focus group interview was also conducted. Data from these sources indicated that personal transformations had taken place with some students referring to a commitment to learn more, a commitment to take action on an issue of interest to them, having a sense of greater responsibility and so on.

Evidence that transformations related to learning was also found. Students reported enjoying the model of learning used where they were contributors to the learning and a respected part of the process. A desire to continue learning about global issues in a Bridge21 style was also reported by the students.

Incorporating learning

Following on from this engagement, GOAL would seek to incorporate the Bridge21 model of learning into other Development Education workshops and would encourage others to also explore the model. Using the Bridge21 model gave students opportunity to work in teams to create digital artefacts (slideshows, videos and radio shows) that enhance the learning and allow students to continue in the learning.

The use of technology allowed for great independence as students had to learn and create unaided by the teacher. Furthermore, working in a team empowered students – each student utilised their respective skills to the benefit of the team to create something greater than the sum of their parts.

The model of learning allowed students to break free of traditional classroom constraints. They become partners in learning with the teacher and were given responsibility for their own learning. The students were learners, researchers and creators and had the opportunity to shape their activities and outputs. Most importantly, their views mattered and their inputs and outputs were a valued part of the learning experience.