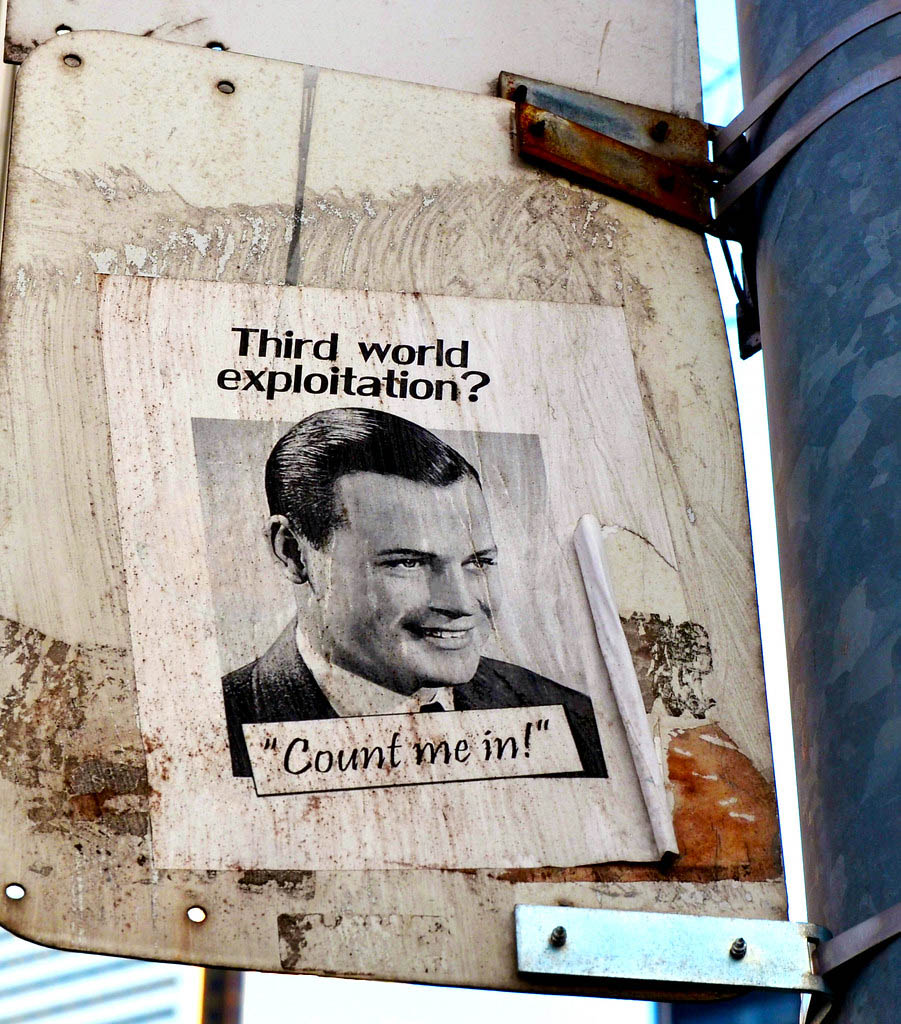

Photo: third world exploitation poster spotted in Toronto (Jan 26, 2013) by Mary Crandall. CC NC-ND 2.0 license via Flickr

Photo: third world exploitation poster spotted in Toronto (Jan 26, 2013) by Mary Crandall. CC NC-ND 2.0 license via Flickr

Recent years have witnessed many ongoing calls for a ‘definitive definition’ of development education (DE) and failing that for abandoning the term in favour of, inter alia, human rights education, education for sustainable development or global education etc.

The argument is often put forward that ‘development education’ remains ill-defined (this despite the fact that both concepts – development and education – remain hotly contested generally) and that the ‘public’ will understand our work better if it is re-labelled (usually little or no evidence is offered for this proposition) etc.

While personally I find this debate tiring and unproductive (and a distraction from the work itself), I feel it may be worth re-iterating the roots of our work and why the term development education is important and accurate and why abandoning it would weaken and dilute our agenda considerably (particularly from an NGO perspective). The debate may also become more immediate in light of the upcoming review of Irish Aid’s development education strategy where I suspect the term Development Education will once more be questioned.

While the history of development education requires a more detailed treatment than is possible here; its roots date back to the post WW2 era and have specific contexts and politics (unfortunately too many ‘histories’ of the subject date its origins much later in the 1970’s for example thus ignoring a very rich vein of history and pedigree).

There have been many twists and turns in its story as it gained leverage within the broader development cooperation agenda and, more broadly, in the educational agenda in Ireland as well as internationally. While this is a story for another day, it may be useful to briefly identify 3 core elements of DE that highlight its specificity and which contribute much to our attempts to understand (and, more importantly) to change the world.

These core components also highlight other challenges and tensions – those between civil society and the state on human development issues; those between the charity and justice perspectives within DE; those surrounding the debate on the political nature of DE and how it has to a significant degree been diluted in recent decades and the degree to which too many NGO have forsaken their role in DE as that of the state has increased.

Again, these are issues that will have to await another day.

For now (and to stimulate debate), 3 core components of DE (there are clearly many others):

- DE has a specific and unique pedigree rooted primarily but by no means exclusively in the lived experiences of aid and development workers and organisations (primarily missionary, NGO and (inter) governmental) overwhelmingly working amongst the poorest people and communities in Africa, Latin America and Asia (there is another rich strand emanating from those working with marginalised communities in the ‘developed world’). The need for DE grew directly from the lessons and experiences of those working in such contexts and the need to highlight the plight of the worlds excluded, oppressed, poor and hungry and to attempt to galvanise action internationally. As such DE ‘has field dirt under its fingernails’ – a dirt that gives it a legitimacy (speaking from a lived experience) and an immediacy (politics). In such a context DE, especially as promoted by many missionaries and NGOs is specifically political, something we are in danger of losing as DE becomes institutionalised.

- DE has always had a strong ‘Third Worldist’ view of human development and human rights; it approaches and engages with the issues through the eyes, mouths and hearts of those at the wrong end of colonialism, imperialism and more recently neo-liberalism. It poses the question as to how an issue is seen, experienced and spoken about by a poor female farmer in sub-Saharan Africa, a favela dweller in Sao Paolo; a dalit in India or a coffee plantation worker in Colombia. Its politics, philosophy and pedagogy are rooted firmly (if not exclusively) in Third Worldist analysis, writing and advocacy. Again, this is something we are in danger of losing to the detriment of our agenda.

- DE has an explicit focus on the worlds poorest – to coin a phrase from Catholic Social Teaching, it has a ‘preferential option for the poor’. It’s bread and butter issues include hunger, undernutrition and malnutrition, basic needs in education and health (especially for women), water and sanitation, the cost of staples, basic human security and human rights etc. (and there are many more etceteras…). DE insists that the needs of the poorest take precedence in international discussions and debates on human development and human rights and brings this dominant perspective to bear on current debates in sustainability, climate change, the SDGs, ethical trade and consumption etc.

DE’s principal ‘laboratory’ remains alongside the poor and excluded and not in universities, libraries, academic journals and certainly not within a language increasingly accessible to a very limited few. Many of DE’s key reference points are the analyses, arguments and worldviews of writers and activists such as Paulo Freire, Eduardo Galeano, Vandana Shiva, Arundathi Roy, Helder Camara, Wangari Maathai, Amartya Sen, Mahbub Ul Haq etc. as well as in radical educational debate and activism internationally.

As historically practised by many NGOs, DE has as its guiding principal a ‘justice perspective’ – it is not simply concerned with ‘learning’ about the wider world as such, it is about learning about the nature, character and consequences of our 80:20 world. DE is about educational activism; it is about stimulating public debate and discussion about key issues concerning all our futures.

In current debates, we would do well to reconsider some of our roots and histories and not be swept along, willy nilly by the latest theory or fashion – our roots are strong, specific and political – we lose them at our peril.

This blog is the first in a series of blogs reflecting on the history, ideas and practices of development education in Ireland.