In these days of ‘crisis’ summit meetings, ‘floods’ of migrants ‘swarming’ at borders, ‘security’ forces ‘overwhelmed’ and Europe facing an ‘unprecedented’ crisis, words take on added significance as we search for a language that matches our feelings.

How we describe the situation, how we construct its meaning and contours, how we build its current and future geography, the signals and messages we offer others and how we contribute to public dialogue becomes hugely significant. Words evoke emotions, emotions generate responses, responses imply (in)action and all create consequences.

What is now happening in Europe is not happening in a vacuum; it is but the latest verse in a long story of history and geography; it is a verse that excavates the very meaning of the word ‘Europe’ and what it means to be ‘European’ in the contemporary world.

I go back to an important mentor, the brilliant John Berger (Ways of Seeing, A Seventh Man, Pig Earth etc.) who comments on the link between words and stories:

“When we read a story, we inhabit it. The covers of the book are like a roof and four walls. What is to happen next will take place within the four walls of the story. And this is possible because the story’s voice makes everything its own.”

– Keeping a Rendezvous (1990)

We are continually building, demolishing and re-building the European story and the parameters and ‘guts’ of that story; it will partly define us and the legacy we pass on to those immediately behind (for me, Dylan, Ruby and Donny).

For all of us, this is an intensely personal story and for those currently the ‘villains’ or ‘victims’ of that story, it could not be more personal.

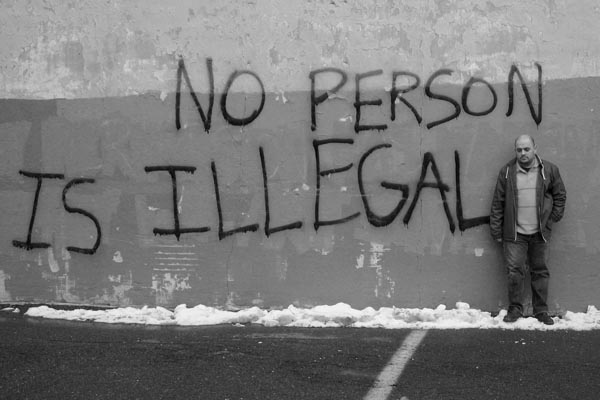

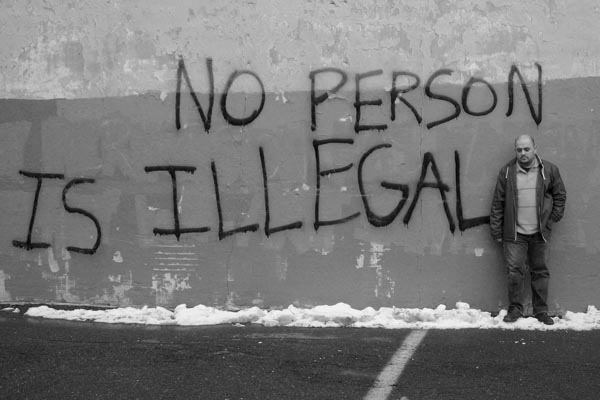

That word ‘illegal’: it points, suggests and accuses, simultaneously revealing and concealing so much.

The term ‘illegal’ itself: legally incorrect (being ‘undocumented’ is not a ‘crime’ but an administrative category; it is not an offence against persons, property or even ‘security’); it makes little sense as children are deemed ‘illegal’; it denies international law (designed precisely to prevent states designating anyone as less than a legal person).

And it violates; it violates a fundamental right – that of ‘due process’ without which we are all ‘guilty’. Fleeing is not in itself an offence either – waiting for ‘permission’ or ‘legal documentation’ a smug fiction for the safe and secure.

‘Illegal’ dehumanises, degrades and denies inherent dignity; it justifies punitive responses; it stimulates ‘policing’, ‘detention’ and ‘restrictions’; it ‘criminalises’ (even those who help) and thus separates out (‘they’).

It echoes evil chapters of Europe’s history.

‘Illegal’ inhibits debate, undermines ‘truth’, prejudices judgements, outcomes and basic humanity – ‘theirs’ and ours.

And, of course, it avoids reality – the realities that create and mould the context – poverty, oppression, rape, killing, discrimination as against safety, protection, life and hope.

‘Illegal’ denies human solidarity, encourages self-centredness and putative superiority; it eschews inclusion in favour of exclusion; it eats away at any deeper sense of humanity at immense costs to all. ‘Illegal’ fosters suspicion, mistrust, hostility and eventually violence (of many types). It erodes a fundamental value all need in creating a meaningful future – that of community and social cohesion.

‘Illegal’ is inappropriate, discriminatory, oppressive and harmful for all of us; if we do not challenge it, we are threatened with re-living a European history we vowed to leave behind.

As someone who believes strongly in the ‘European Project’, ‘illegal’ shames me. In the context of Turkey, Greece, Macedonia, Hungary….it should shame us all.

To finish, John Berger again:

“Everything in life, is a question of drawing a line, John, and you have to decide for yourself where to draw it. You can’t draw it for others. You can try, of course, but it doesn’t work. People obeying rules laid down my somebody else is not the same thing as respecting life. And if you want to respect life, you have to draw a line.”

– Here is Where We Meet: A Fiction

A note to readers: at the beginning of Keeping a Rendezvous – a collection of essays published in 1992, John Berger comments:

“I hope readers too will find themselves saying: I’ve been here…”