Duncan Green’s How Change Happens (Oxford University Press 2016) is an excellent resource for a variety of conceptual and practical reasons. It is also a book of, and for, our times, not only for its perceptive analysis of the change process as perceived by activists but also as a potential agenda of ideas and suggestions for those of us involved generally but, for us, in educational activism in particular. And, unlike many other analyses of the subject, it is written in an engaged, accessible and readily ‘processed’ manner. Given Bill McKibben’s assertion (in the context of climate change) that ‘we are all activists now’, How Change Happens deserves the widest possible audience and debate. Additionally, from our perspective it also includes much food for thought (and debate) for development educators per se.

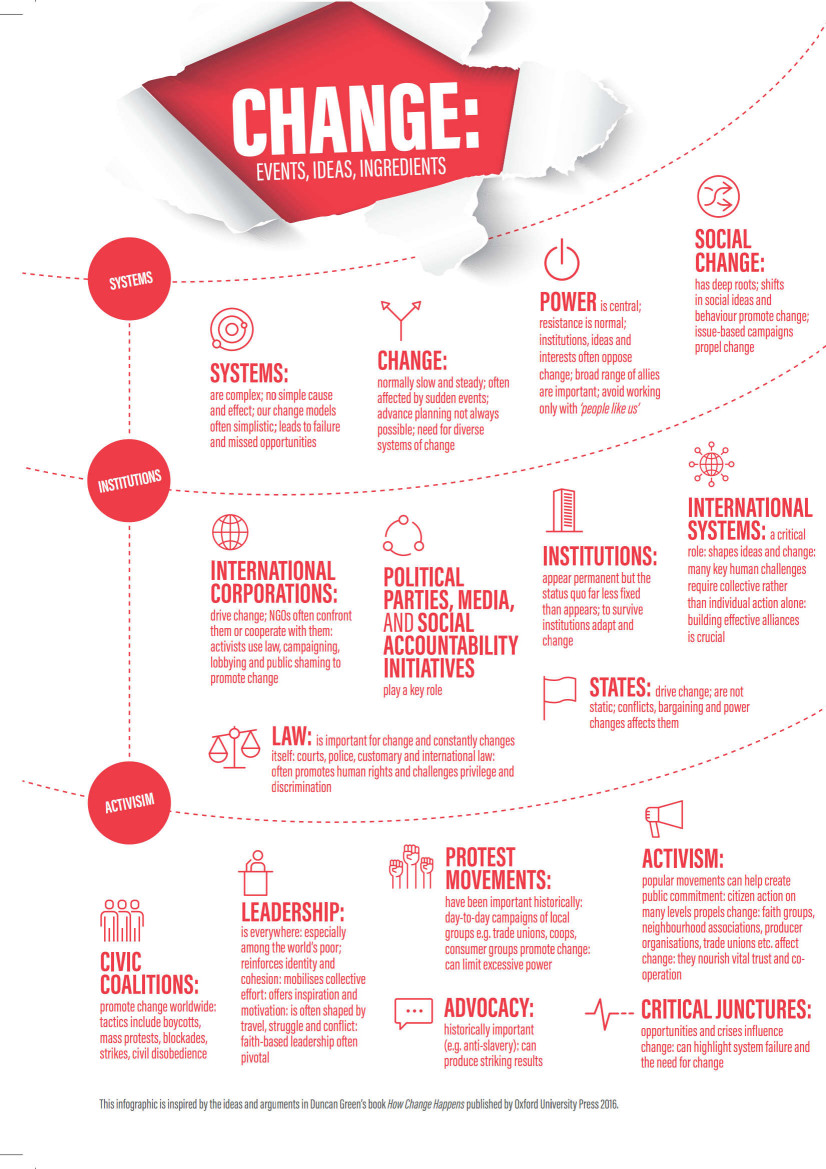

The book is in four parts and analyses what Green describes as a ‘power and systems approach’, with useful overviews in the first Part on power itself, on systems and on the shifting social norms that underpin change (including views on women and gender, the state, culture and faith etc.). Part 2 discusses a number of key contexts or sites, in which change happens – the state, the law, politics, the international system and transnational corporations. Part 3 debates what activists can and cannot do, including reference to citizens’ action, leadership and advocacy. The final part summarises the analysis together with a conclusion that highlights key challenges and possibilities for activists.

Green concludes, ‘Despite setbacks and the grim filter of the evening news, the story is overwhelmingly positive’ – a conclusion we would do well to remember in these particularly grim times. The book is rooted in a wide review of literature from many disciplines, Green’s own experiences, extensive quotation, anecdotes and case studies from Oxfam’s wide ranging work.

For those wanting a quick overview of the book, Green has included a two-page summary at the beginning of the book and we have provided a graphic summary:

Green offers those reading the book from an educational context a particularly useful and interesting one pager (page 8) relating to a ‘power and systems approach’ (PSA) as presented in the table below:

How we think/feel/work: 4 steps to help us dance with the system

The questions we ask (and keep asking):

Source: A Power and Systems Approach, p.8 from How Change Happens. |

From our vantage point, a number of propositions from the book are worth highlighting:

- Systems thinking implies complexity, there are no simple answers or solutions, therefore multiple strategies are needed and not just one.

- Links and alliances with a host of structures, organisations and institutions are vital, including those possible and appropriate with TNCs, multilateral institutions, churches etc.

- Activists need to be self-aware – aware of own prejudices and perspectives.

- Multiple perspectives are important in pursuing our agendas.

- Recognizing the central role of power – people’s own inner power ‘within’; power through organizing and joint action and institutional power across societies.

There are many interesting and useful sections for development education, for example:

- The world is complex – so what? (pages 19-22)

- Why change doesn’t happen (pages 41-44)

- Female Genital Mutilation campaign – how the movement framed the campaign as a human rights issue (pages 62-65)

- International law (pages 106-109)

- Hard and soft power (pages 140-145)

- Civil society and the state: opponents or collaborators? (pages 187 – 190)

- How advocacy works (pages 215 – 221)

In assessing Green’s book from a development education perspective, there are several significant omissions in our view.

Exploring the role of advancing ‘public conversations’

In discussing leaders and leadership (chapter 10) and citizen activism and civil society (chapter 11) there is little reference to literature and case studies on how public judgement is shaped and informed on key issues. While leadership is essential, developing a critical and engaged threshold of people involved in and/or supporting campaigns and public conversations is vital – it creates a key context in which leadership can operate. Whether initiated in schools, colleges, adult education, youth, professional, faith or business contexts debating and coming to judgement on ethical, political, economic, environmental, rights issues etc. the building up of public debate from diverse directions is fundamental.

Working through and debating issues is an essential ingredient in the change mix. Social norms have (as Green acknowledges) been changed through public information, awareness and moments of public judgement (shock moments or crisis events) present learning opportunities for working through many ‘emotional resistances’). The Northern Ireland peace process, for example, was advanced pivotally when the ‘public’ created the context in which politicians could deliver or were forced to deliver.

Human Rights traditions and approaches as a fundamental activist tool

The references to human rights traditions, procedures and architecture are significantly underdeveloped in How Change Happens. Green offers summative passages on developing a culture of human rights norms:

‘A study of how governments come to adopt and implement new human rights norms identified five stages: repression (of those promoting the norm); denial (refusal to acknowledge the issue); tactical concessions (just enough to keep critics quiet); prescriptive status (starting to adopt the spirit of the new norm by ratifying international treaties, changing domestic laws, or setting up new institutions); and rule-consistent behaviour (putting mechanisms in place to ensure the new norms are respected)’ – page 56, How Change Happens, 2016.

For us, contextualising how human rights ‘came to be’ – its global origins as expressed in the Preamble of the Universal Declaration for Human Rights and the host of subsequent international instruments, procedures and structures (and the movements that generated many of them) would, we feel, have strengthened the book. Without doubt, the principles and values embodied in the human rights movement are visible, but the connections from these to core underlying human rights contexts are a lot harder to find.

The role of learning processes as platforms for change

The PSA approach is rich tool for reflection, whether by an individual, a group of individuals working together or as part of strategic planning conversations in organisations. While education institutions (e.g. the role of the state in supporting public education on rights and values in citizen activism) and learning through training (through footnoted references to active citizenship projects and key takeaway lessons) are covered, the role of learning processes as amongst the broadest platforms for change are missing from the book.

The ingredients are certainly present as part of individual reflection exercises. For example, how South African dockworkers refused to unload an arms shipment from China headed for Zimbabwe and how the campaign promptly highlighted both the effectiveness of the action, and the human cost it prevented within the context of Arms Trade Treaty campaign in 2008 (see chapter 7) gives us a flavor of the public learning (and engagement / interest / exemplar activities) in such actions as part of a larger context.

The contribution of human rights education and development education to the ‘change mix’

Strangely development or human rights education is also missing from How Change Happens despite its key role historically in campaigns on, for example, ending Apartheid, Central America, Nestle, Fairtrade etc. Exploring the role of diverse groups of people in debating and acting on the Behind the Brands campaign or the broad Fairtrade agenda as examples of public conversations in building a groundswell of public pressure and engagement highlights the key role of education. As part of a broader discussion, it would be hugely interesting to review the role of education-based initiatives in building public awareness in, for example the discussion (in chapter 8) on transnational corporations as drivers of change through the actions (and inactions) and behaviour of consumers, investors/pension fund managers, industry peers and others. Certainly, in our view the role of education in building the Fairtrade movement and debate has been pivotal.

One of the key questions a book such as How Change Happens evokes is inevitably ‘what can I do?’ and DE has historically offered a platform for discussing action ideas, particular roles and responsibilities as well as opportunities.

Student activism and the distinctive contributions of young people to change agendas

The role of young activists and the challenges they routinely pose to adults are largely overlooked. While Green appreciates that JK Rowling and JRR Tolkien are among some of the most powerful influences on the next generation, student and youth activism and examples of the challenges they offer to the speed, direction and tactics of change are absent from How Change Happens. Whether exploring the ‘Umbrella Revolution’ in Hong Kong in 2014, the challenge to universities and education through the 2015 Rhodes Must Fall protests initiated in South Africa or the college campus ban of Coke Cola products in University College Dublin in 2003, young people offer countless examples in the change mix as natural adopters of ‘positive deviance’ approaches often ahead of mainstream activist responses.

The book (and the conversations it has generated) would benefit from additional ‘cooking’ in this context; many of the ingredients for such work, drawn from the book, are clearly identified:

- The ‘learning by doing’ approach as presented in theories of change in chapter 12 critiques strategies and ideas for moving beyond ‘command and control’ approaches to challenge the straitjackets of working to ‘logframes on steroids’ (performance frameworks on steroids?)

- Considering more the choices available in adopting an ‘insider’ or ‘outsider’ activist approach with those in power and the kinds of tactics for raising public awareness because of those decisions.

- Adopting ‘positive deviance’ approaches: embracing outliers and behavioural change that occurs from within a given community as ‘for any given problem, someone in the community will have already identified a solution’ (chapter 1).

- History and learning from the past (p76).

Duncan’s book (and more importantly the conversations it has and will provoke) are fundamental to our whole agenda whether in policy, advocacy, campaigning or education contexts. It deserves to be read thoroughly.

- This blog was prepared as part of the event How Change Happens: The Role of Politics, the Media and Civil Society co-organised by Dóchas, Oxfam and 80:20 Educating and Acting for a Better World that took place on 15th February 2017 in Dublin.

- The event coincided with the release of the 7th edition of 80-20 Development in an Unequal World edited by Tony Daly, Ciara Regan and Colm Regan, and Duncan Green’s newest publication How Change Happens.