What The Fact?

'Aid doesn't work'

Local women help unload humanitarian aid from a World Food Programme helicopter in Bebedo, Mozambique during humanitarian relief efforts in the Republic of Mozambique and surrounding areas following Cyclone Idai, (April 8, 2019). Photo: Thomas Grimes/USAFRICOM (via Flickr under CC-BY 2.0 licence)

- Colm Regan

The Claim

We have all heard it, time and time again – international aid just doesn’t work. It doesn’t achieve its objectives, it wastes money and it would be better spent here at home.

A representative example of the argument is offered by Tim Worstall, a Fellow at the Adam Smith Institute in London (the Institute publishes many similar arguments). He outlines his view in a piece published in Forbes Magazine in October 2015:

“Development aid doesn’t work then. Again, to emphasise, this is not about emergency aid, food to the starving, aid to those struggling after an earthquake. This is about the official development aid that governments hand out from our taxes.

And, as the finding above shows [Worstall is referring to a research report from 2015 economic growth] it doesn’t work. Not only doesn’t it work, the aid we give for political reasons works less well than that. We should, therefore, simply stop doing this. Which is as some of us have thought for a long time.”

Source: Forbes Magazine, 2015

The Verdict

The argument offered by Worstall on aid not working is false on three levels.

- The argument offered by Worstall (and others) is based on a highly selective set of readings

- It selectively comments on some types of aid arguing that it does not work and then applies this argument to all aid

- It does not acknowledge or admit that much aid (but not all aid) does in fact achieve its objectives and does impact positively on many of the world’s poor.

The Evidence

Worstall refers to the an article published on a website that promotes research-based policy analysis and commentary by “leading economists”, VoxEU.org, to support his claim, written by researchers Axel Dreher, Vera Eichenauer, Kai Gehring, Sarah Langlotz, Steffen Lohmann. However, far from stating that aid doesn’t work, the authors of the report cited argue in their introduction:

‘Despite a large number of academic articles, this literature has not reached a consensus’.

The authors of the study go on to conclude:

‘…there is no robust evidence that aid affects growth. Of course, this does not imply that aid is necessarily ineffective. Much of the aid is not given to affect growth in the first place. A large share is given as humanitarian aid following disasters. Parts of aid are given to fight terror, please political allies, or influence decisions in important international organisations. As we have discussed above, the motive can affect the outcome. Such aid thus cannot be expected to increase growth but should instead be evaluated with its own goals in mind.’

Moving from their conclusion to asserting that aid doesn’t work and therefore should be stopped (as Worstall does) is both misleading and false.

In contrast to the argument offered by Worstall and in the search for a broad range of research, evidence and findings on the debate, two sources offer a good starting point:

Research fellow at the Brookings Institute, Washington, Steve Radelet, concluded in his 2017 blog Once more into the breach: Does foreign aid work? that:

‘It is important not to overstate the impact of aid. Foreign aid has not been the major driver of development progress over the last 20 years, nor will it be in the future. Long-term development progress depends primarily on the economic and political institutions that are built over time in low-income countries, and the actions taken by those countries themselves. Aid programs (alongside diplomacy and other tools of international engagement) are not the driving force behind development, but they can help support development progress along the way.’

A second source with a broad remit in the debate is offered by Andy Sumner (2014) of the Centre for Global Development at Washington, DC, The $138.5 Billion Question: When Does Foreign Aid Work?. Based on his and his colleagues research, four conclusions emerge:

- Aid is more likely to work in the correct dosage but is ineffective if too high or too low

- Aid is more likely to work if the institutions are in place—for example, political stability and not too much decentralisation

- Aid is likely to be more effective in certain sectors and aid objectives and time horizons matter a lot

- Aid is likely to be more effective if it is not volatile and fragmented

Sumner concludes

’… shifting the debate from whether aid ‘works’ to when aid works and how it can work better would contribute to better aid policy decisions in the real world, move away from mostly theatrical claims and counterclaims, and might even serve to reinvigorate global support for aid.’

| Different Types of Aid | |

|---|---|

| Main aid mechanisms | Programme aid including overall recipient government budget support (general or sector specific e.g. education or health); project support to or via NGOs (local and international); support to or via public-private partnerships and technical assistance. |

| Main types of ‘flow’ | Grants, concessional loans, debt relief, equity purchase |

| Varied stated objectives of aid | Short-term human development results; capacity strengthening (institutional and human); policy change; economic growth and (income) poverty reduction; climate and other international public goods; research and technological advance and security concern |

| Four motivations of aid | Short-term human development results; capacity strengthening (institutional and human); policy change; economic growth and (income) poverty reduction; climate and other international public goods; research and technological advance and security concern |

| Aid supports different sectors (OECD categories) | Social services and infrastructure (education, health, water, government and civil society, peace and security); economic services and infrastructure (transport, communications, energy, banking); production (agriculture, industry, trade, tourism); commodities and general programme support (food, general budget support); debt relief, humanitarian and unspecified. |

Table source: The US$138.5 Billion Question: When Does Foreign Aid Work (and When Doesn’t It)? Jonathan Glennie and Andy Sumner, Center for Global Development Policy Paper 049, November 2014:15/16

Note from source authors: ‘… there will be plenty of overlap between the categories (in the diagram above) – they are meant primarily to illustrate the diversity of intervention which complicates the apparently simple question, does aid work? At one extreme, some interventions might be quite short term, local, and with empirically verifiable outcomes (such as an attempt to reduce the prevalence of malaria in a particular geographic location). At the other, some aid interventions may be intended to support long-term change nationally, making progress hard to measure (such as general budget support). There is no reason, a priori, why all types of intervention should or shouldn’t work in general.’

On the impact of aid

There is little disagreement internationally that overall human development worldwide has improved in all key dimensions over the past 30 years – in relation to poverty, health, basic education, access to core services such as water and sanitation and yet huge inequalities remain and are even growing. The improvement in human development cannot primarily be attributed to aid and its impact but there is little doubt that aid has been a part of the story.

In their detailed study completed in 2014, The $138.5 Billion Question: When Does Foreign Aid Work? (and when doesn’t it?), by the Washington-based Centre for Global Development, Andy Sumner and his colleague Jonathan Glennie concluded:

‘Broadly speaking … over the last decade, (studies) have been more positive on the role aid can play in these areas than previous generations which should, for now at least, give aid’s critics some pause for thought – the public debate, which often seems divided between the pro- and anti-aid camps, has some way to go to catch up with the balance of the evidence. However, we have also cast further doubt on the legitimacy of generalised ‘aid works’ and ‘aid doesn’t work’ claims … we propose a set of factors that determine when aid is most likely to work… (i) the country context, meaning the characteristics of the recipient country and national government policies; and (ii) aid management, meaning the characteristics of aid and donor policies and practices.’ (2014:43)

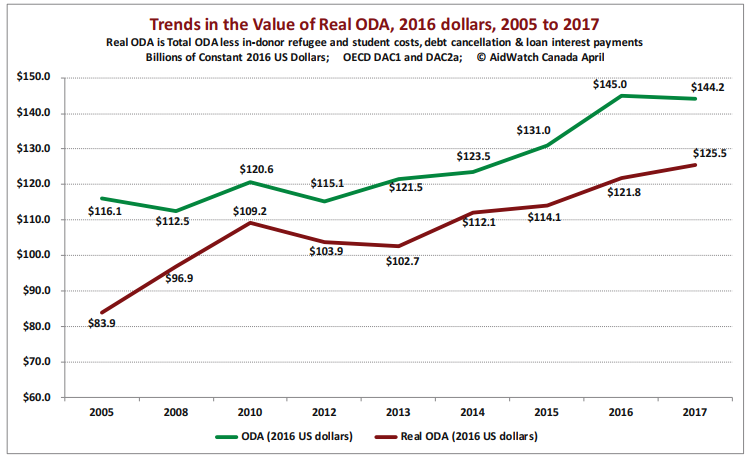

For an analysis and discussion of the serious shortcomings of aid in the most recent years, see The Reality of Aid Report 2018 especially chapter 4 on global aid trends.

Aid: A contributing factor

Worldwide, aid has also helped towards achieving remarkable successes. Dóchas, the Irish Association of Non-Governmental Development Organisations, in their Overseas Aid – Fiction or Fact leaflet in 2016, drew on official UN data to highlight, for example:

- Between 2000 and 2011, the number of children out of school declined by almost half — from 102 million to 57 million.

- The maternal mortality ratio declined by 47% since 1990.

- The mortality rate for children under five dropped by 41% between 1990 and 2011.

- The number of new HIV infections per 100 adults (aged 15 to 49) declined by 44% between 2001 and 2012.

Conclusion

Stating baldly that aid doesn’t work and citing some selected studies to ‘prove this’ is both disingenuous and false.

In arguing the issue, it is important not to overstate the importance and pact of aid. As the research suggests that while foreign aid has not been the major driver of development over the last 20 years, it equally will not be in the future. Long-term human development worldwide is a function of economic and political institutions built over time across all regions.

Aid agendas alongside other tools of international involvement such as diplomacy cannot and will not deliver development (nor are they designed to) but they can and do support human progress and well-being along the way.

Verdict

Based on the What The Fact? scales guide, the claim is rated as False – the claim is inaccurate based on the best evidence publicly available at this time.

Sources

- Proof That Government Development Aid Doesn’t Produce Economic Growth by Tim Worstall in Forbes Magazine, October 15, 2015

- Does foreign aid effect growth? by Axel Dreher, Vera Eichenauer, Kai Gehring, Sarah Langlotz, Steffen Lohmann on VOXEU.org, October 18, 2015

- Overseas Aid: Fiction & Fact – setting the record straight about Aid by Dóchas, 2016

- The $138.5 Billion Question: When Does Foreign Aid Work? by Andy Sumner on the Centre for Global Development blog, December 9, 2014

- The $138.5 Billion Question: When Does Foreign Aid Work (and When Doesn’t It)? by Jonathan Glennie and Andy Sumner in Centre for Global Development Policy Paper 049, November 19, 2014

- The Reality of Aid Report 2018 by the Reality of Aid Network, January 16, 2019

- Once more into the breach: Does foreign aid work? by Steve Radelet, Brookings Institute, May 8, 2017

_______________

developmenteducation.ie’s What The Fact? supports the code of principles of the International Fact Checking Network. We check claims by influencers, from local to national to transnational that relate to human rights and international human development.

Transparent fact checking is a powerful instrument of accountability, and we need your help.

Send tips and ideas to facts@developmenteducation.ie

Join the conversation #whatDEfact on Twitter @DevEdIreland and Facebook @DevEdIreland