What The Fact?

'Environmental problems are easier to solve with fewer people'

A large crowd, taken just after a Muse concert in Paris, (June 23, 2007). Photo: James Cridland (via Flickr under CC-BY 2.0 license). Colours modified

- Toni Pyke

The Claim

“All our environmental problems become easier to solve with fewer people, and harder — and ultimately impossible — to solve with ever more people.”

Source: Sir David Attenborough, natural history broadcaster and patron of Population Matters

(quoted from Population Matters website)

The Verdict

The argument offered by Attenborough on overpopulation is misleading on four levels:

1. Future projections demonstrate a declining global population

2. Focusing on reducing global fertility will not have an immediate impact on the current global climate crisis

3. Responding to the challenges of our environment requires a serious multi-focused approach and action plan.

4. Endless economic growth that continues to demand and extract non-renewal energy sources (fossil fuels) and facilitates overconsumption is limiting the earth’s capacity to regenerate, rather than as a result of global population growth.

The Evidence

Advocates of ideas linked to overpopulation, such as campaigning charity Population Matter, claim that unsustainable increases in global population statistics are the root of “almost all of the major problems facing us today”, that is ‘multiple environmental threats… poverty, conflict, resource depletion and a poorer quality of life for many people”.

Population Matters states:

We have only one Earth. Today, the 7.7bn people on it are using more of its resources than it can provide. Every new person is a new consumer, adding to that demand. There are many steps we must take to make our consumption sustainable – adding fewer new consumers is one of them”.

The ‘fear’ of too many people eating from the same pot of resources gathers momentum through a perspective that to enjoy a ‘welfare state: a paradise on earth’ we are led to aspire to, our ‘quality of life comparable to that enjoyed in the European Union’ is limited to 3 billion people. This perspective, championed by the Netherlands-based Ten Million Club Foundation, sees ‘overpopulation as the common denominator of most social problems’. (for more, see articles by Paul Gerbrands on their website overpopulationawareness.org). Otherwise, some believe that without our current standard of consumption our quality of life will reduce to ‘that of a poor farmer who can scarcely provide sufficient food for himself and knows nothing of welfare’.

An area of ongoing concern for many campaigners of policies to control family planning, such as Population Matters, the Ten Million Club Foundation and Endangered Species Condoms, Paul and Anne Ehrlich’s book The Population Bomb (1968), Sir David Attenborough, Dr. Jane Goodall and many more) is that a rising global human population is consuming more resources than our planet can regenerate. Their central claim is that the resulting loss of biodiversity, climate change, pollution, deforestation, water and food shortages are intensified by increases in population size, and if we continue on this uncontrolled reproductive path, by the next 3 decades we would need 3 earths to sustain us.

(Over)population and hunger – 'Malthus’s Zombie'

The fear that links overpopulation and declining natural resources is not new. It dates back as early as 1798 when the Reverend Thomas Robert Malthus popularised the argument that if we don’t control global population levels then the earth has a ‘natural tendency’ to curb it for us – through famine – that is, ‘gigantic inevitable famine’ which, ‘with one mighty blow levels the population with the food of the world’.

David Attenborough, who has emphasised that he is not an economist, sociologist or politician, approaches questions relating to the link between human population growth and famine as an expert on animals and ecology:

“I am not an economist, nor a sociologist, nor a politician, and it is from their disciplines that answers must come. But I am a naturalist. Being one means that I know something of the factors that keep populations of different species of animals within bounds and what happens when they aren’t.

Because of our intelligence, and our ever-increasing skills and sophisticated technologies, we can avoid such brutalities. We have medicines that prevent our children from dying of disease. We have developed ways of growing increasing amounts of food. But we have removed the limiters that keep animal populations in check.”

Malthusian philosophy (mutated now as ‘neo’-Malthusian) continues to hold popular momentum today and is regularly resurrected ‘to terrify the living’, as famine research veteran and executive director of the World Peace Foundation Alex de Waal points out in his 2018 book Mass Starvation: The History and Future of Famine (See short videos by de Waal 1 & 2).

In his book, de Waal goes to great lengths to demystify the link between insufficient food supply and the (over)population debate. Disputing Attenborough as a long-standing advocate of “limiters” for population control on his comments about ‘all these famines in Ethiopia’ because there are too many people, de Waal reports that:

“Food production is not the constraining factor on humanity today nor in any foreseeable scenario in which we have political economies.”

An important point that de Waal makes in relation to the now over-exploited references and links to ‘Famine in Ethiopia’ and the need for population control, is to remind us that famines have since ‘disappeared’ in Ethiopia, despite a four-fold population increase.

People throughout the world, reports de Waal, go hungry because our global economic and political systems, which he calls the ‘political marketplace’, distribute it unfairly and in some cases, political strategies encourage it – such as the Third Reich ‘Hunger Plan’ during the 1940s where ‘hunger’ is used as a weapon of war, or rising food prices that encourage ‘food wars’ and indeed the Irish famine which was strategically ignored by the political elite. He continues that of the ‘famines’ experienced in modern history and those currently being experienced, only the famine in Somalia can directly be linked to climate change. The link, he argues, is “always political”.

The population ‘limiter’– a taboo debate?

In an interesting discussion on the negative impacts of ‘liberal capitalism’ (an enabler of high mass consumption), Dutch historian and executive director of the Ten Million Club Foundation, Paul J. Gerbrands, highlights that too many consumers are the primary issue for our environmental realities: ‘the truly important issue is kept out of the spotlight. Overpopulation, as a problem, is denied…’. In his article for the Ten Million Club Foundation website, ‘Why keeping quiet about overpopulation could trigger a global revolution,’ he refers to China as being the only country that considers the implications of (over)population and are ‘opting for fewer people, who will consume more in the future’.

Gerbrands is referring back to 1979 when the Chinese government effected family planning policies through aggressively enforcing a ‘one-child’ policy, which sought to reduce a rapidly growing population and seek to impinge on the anticipated social, economic and environmental problems. In 2015, after nearly 3 decades, the ‘one-child policy’ was lifted.

By 1979 China’s population was 969 million people. Today, China remains the world’s largest population in the world, at 1.38 billion people. The impact of this of the one-child policy on the country’s demographics reveals that:

- Fertility in China did reduce by some 400 million births over the 30 years

- However, the realities of the male preference bias resulted in female babies being aborted/abandoned and distorted China’s gender ratio. There are now more men than women in China

- There are now labour shortages– a larger ageing population unable to work and elderly populations with no-one to care for them. It is expected that the over 60s will comprise 39 per cent of China’s population by 2050. The number of women of childbearing age is expected to fall by more than 39 per cent over the next 10 years.

(Sources: The Guardian; South China Morning Post; Institute for Family Studies; The Straits Times; BBC News)

In illustrating the impact of too many of us wanting ‘paradise on earth’, Gerbrands draws on comparisons of his home country arguing that the population of the Netherlands, at 16 million people, equals the consumption and pollution levels of 200 million people in China. This suggests to him the necessity for Dutch government also to curb fertility levels – currently at 1.62 children per female as compared to China’s now 1.62 children per female.

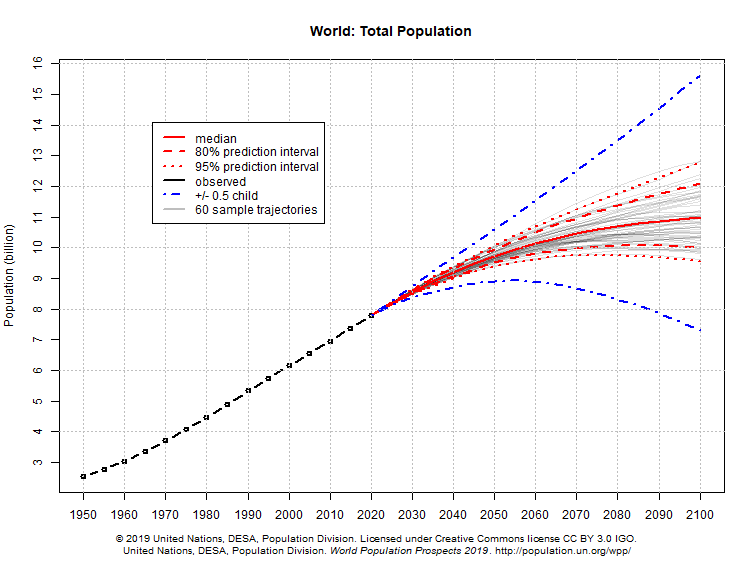

Of note is the United Nations World Population Prospects: The 2017 Revision, which confirms that in recent years fertility has declined in nearly all regions of the world, with expectations that the global population will plateau at 9 billion people by 2050.

The other side of the ‘over’populationist/antinatalist debate

In an interesting counter argument in 2018, Lyman Stone of US digital media company Vox Media News, wrote: “We can’t solve our climate-change problems by having fewer babies”. He argues that the ‘fear’ surrounding the issue of overpopulation is ‘overstated’. From an agricultural economist perspective, he finds that in terms of feeding an increasing population:

the world has plenty of potential for increased food production: more than enough to feed itself and provide imports for a more populous United States.”

Stone also approaches this issue through density comparisons challenging the migration/immigration debate. Using the EU density of 300 people per square mile (as compared to the US population of 110 people), he finds that the EU has a “roughly balanced or even slightly positive agricultural trade”, which as he says, suggest Europe can feed itself despite being 3 times as densely settled than the US.

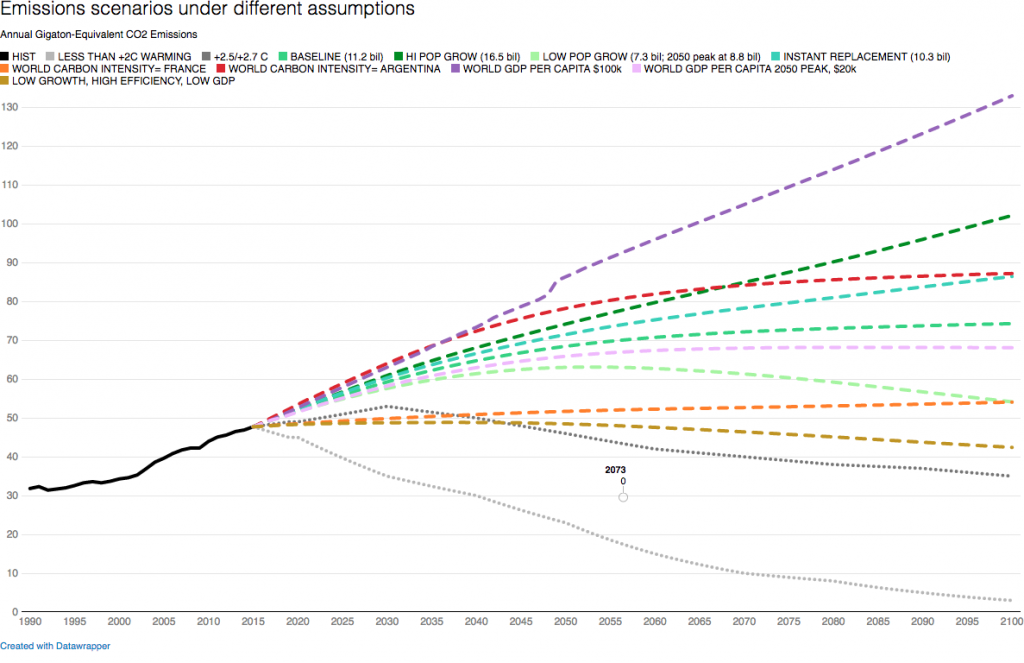

In terms of climate change, he calculates (through population forecasts, GDP per capita and emissions intensity per dollar by country) the emissions estimates that are needed to keep global warming manageable.

Exploring different population scenarios alongside global temperature changes, he shows that to reduce global temperature levels in line with the Paris climate agreement “[n]o amount of population control achieves those goals”, (Paris Agreement levels are agreed as “well below 2 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels and to pursue efforts to limit the temperature increase even further to 1.5 degrees Celsius” UNFCCC).

Another, less discussed challenge, is the ‘higher-intensity consumption by childless couples’. Stone finds that as fertility declines, couples/individuals may offset themselves by foregoing children and may increase their carbon footprint for example, by taking longer haul flights:

…burning extra fossil fuel for airfares and extra driving. … plane ticket alone to Peru would produce between 3 and 7 metric-ton equivalents of CO2. Add in the couple’s double consumption of housing (their home is vacant while they travel), their increase in driving (it’s a road trip), their increase in eating and other consumption (it’s vacation, after all), and that single vacation has about the same carbon impact as a baby in its first year (some 10 tons of carbon, let’s estimate)”.

Higher intensity consumption by childless couples, could increase short-run emissions, which have the largest impact on future temperatures – due to a time delay between carbon emissions and their climate impact.

For Lyman, achieving the necessary reduction in global temperatures is substantially dependent on a dramatic or ‘near total elimination’ of our dependence on fossil fuel in developed countries. This demands a “quantum leap breakthrough in carbon efficiency… fertility on its own won’t make a serious dent… There is only one way to effectively prevent, alleviate, or reverse dangerous climate change: technological, geographic, and social advancement. Population has little to do with it”.

Similarly, Chris Goodall, author of Sustainability: All That Matters, finds that:

“Population reduction would probably reduce carbon emissions but we have many other tools for getting global warming under control…Perhaps more importantly, cutting the number of people on the planet will take hundreds of years. Emissions reduction needs to start now.”

The Climate Mitigation Gap

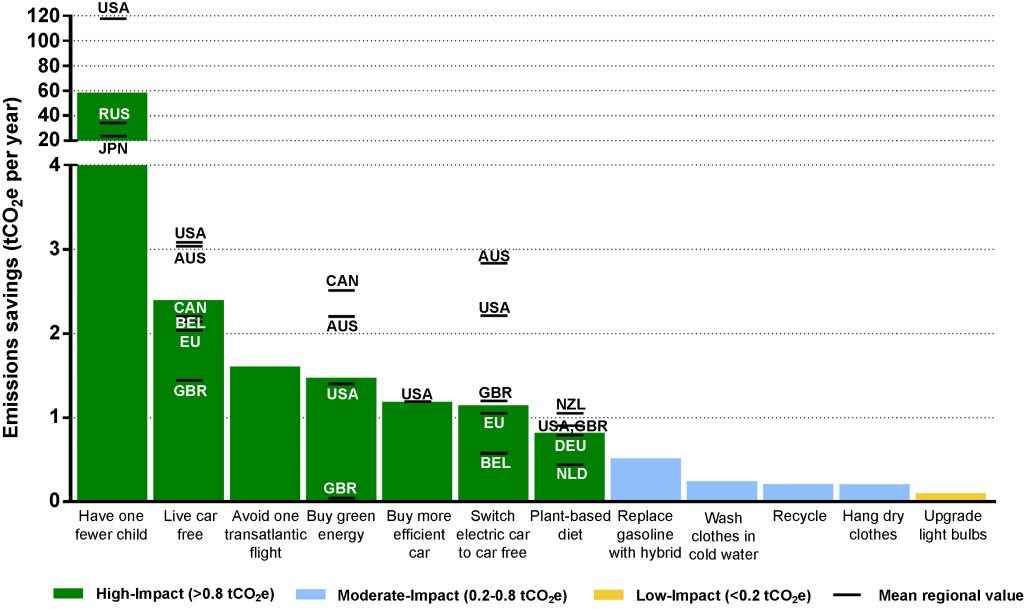

A widely circulated (and hotly debated) study published by Seth Wynes and Kimberly A. Nicholas of Lund University in the journal Environmental Research Letters in 2017 on ‘the climate mitigation gap’, finds that having no, or at least less, children is key to saving the planet – but so is selling your car, not taking long flights and eating a vegetarian diet, which are all necessary actions to reduce our individual footprint and impact on rising global temperatures (in terms of high carbon impact or low carbon impact actions).

Conclusion

Challenging rising global temperatures and environmental devastation is about reducing/eliminating unsustainable behaviour patterns that dictate an over-reliance on non-renewable energy sources.

The climate crisis is current – focusing on having less/no children is a distraction from the immediate, critical, required global responses and interventions.

Endless economic growth that continues to demand and extract non-renewal energy sources (fossil fuels) and facilitates overconsumption is limiting the earth’s capacity to regenerate, rather than as a result of global population growth.

Verdict

Based on the What The Fact? scales guide, the claim is rated as Misleading – elements of the claim are accurate but presented in a way that is misleading.

_______________

developmenteducation.ie’s What The Fact? supports the code of principles of the International Fact Checking Network. We check claims by influencers, from local to national to transnational that relate to human rights and international human development.

Transparent fact checking is a powerful instrument of accountability, and we need your help.

Send tips and ideas to facts@developmenteducation.ie

Join the conversation #whatDEfact on Twitter @DevEdIreland and Facebook @DevEdIreland