3 countries who used COVID-19 restrictions as a weapon against social justice

Kai Evans explores how governments used COVID-19 restrictions for the wrong reasons.

An initial reflection from Indian writer and activist Arundhati Roy:

‘Whatever it is, coronavirus has made the mighty kneel and brought the world to a halt like nothing else could. Our minds are still racing back and forth, longing for a return to “normality”, trying to stitch our future to our past and refusing to acknowledge the rupture. But the rupture exists. And in the midst of this terrible despair, it offers us a chance to rethink the doomsday machine we have built for ourselves. Nothing could be worse than a return to normality.’

The full article provides a searing overview of the realities of COVID-19 in one of the world’s largest democracies, a country Roy calls her ‘poor rich country’.

At the end of April 2020, the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) published two ‘data dashboards’ that highlight the huge inequalities that exist worldwide and the resulting disparities in the ability of poorer countries to respond to the pandemic.

For the UNDP and for most commentators, the pandemic is much more than a global health emergency. It is a systemic human development crisis, already affecting the economic and social dimensions of development in a huge variety of fundamental ways. The virus has added another deadly layer of vulnerability to the deep fault lines that have underpinned our dominant model of ‘development’ in recent decades.

For this author’s commentary of these fault lines, see this.

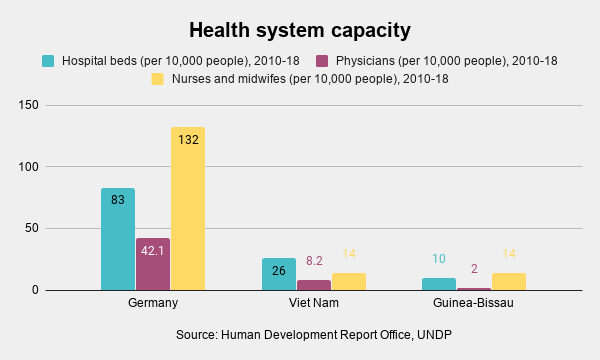

The first data set presented by the UNDP’s Dashboard on Preparedness offers statistics for 189 countries including level of development, inequalities, the capacity of healthcare systems and internet access to explore the existing capacity as well as preparedness to respond to crisis such as COVID-19. The dashboard is colour coded (high, medium and low levels of preparedness) and broken down by region which makes it easy to access and analyse. It graphically highlights the deep fault lines described above.

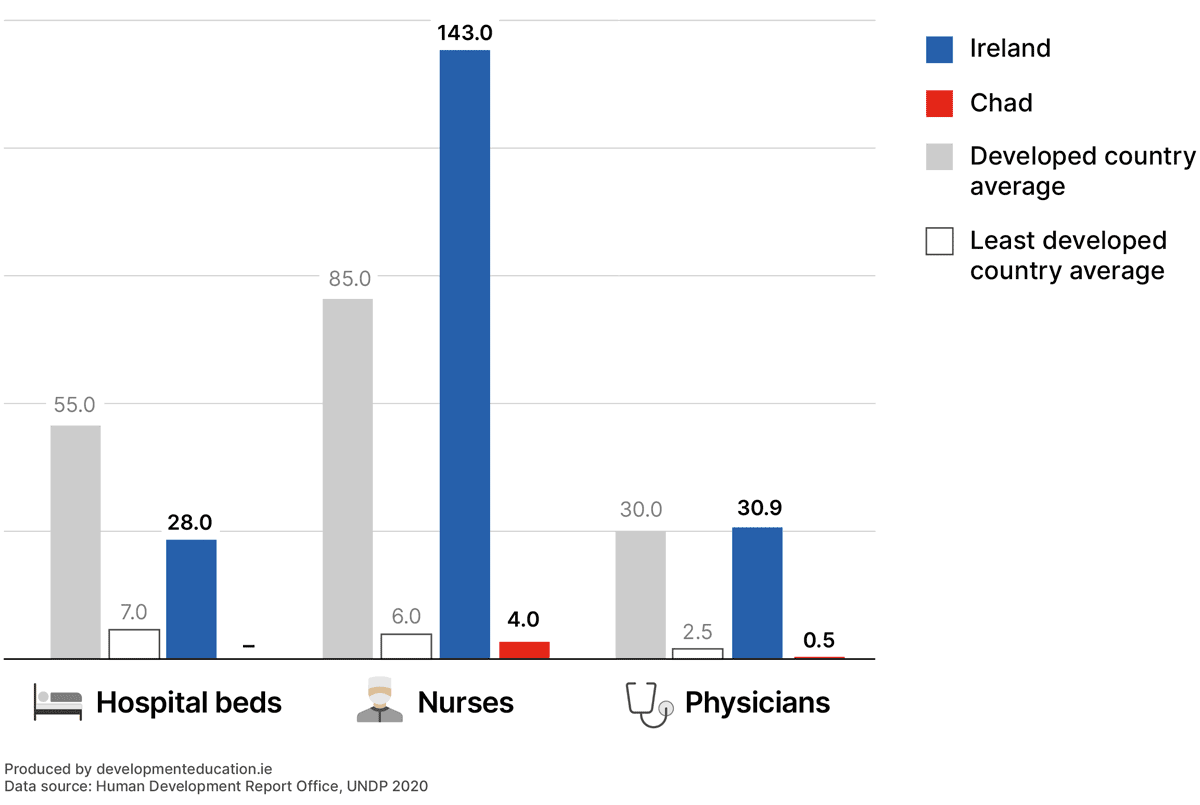

For example, the most developed countries – those in the very high human development category (this includes Ireland) have on average 55 hospital beds, over 30 physicians, and 81 nurses per 10,000 people, compared to 7 hospital beds, 2.5 physicians, and 6 nurses in a least developed country.

The digital divide revealed in the data is now more significant than ever – 6.5 billion people worldwide 85.5% of world population still don’t have access to reliable broadband internet, which limits their ability to work or to continue their education.

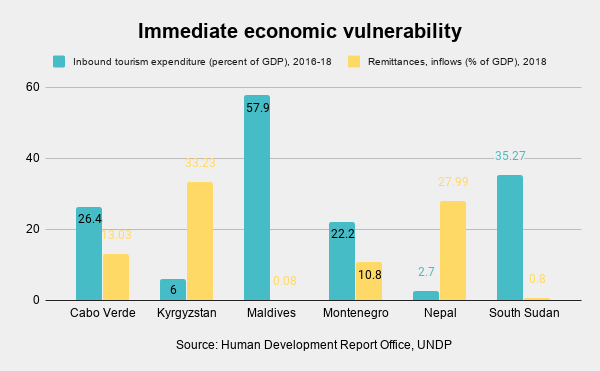

The second data set Dashboard 2 on Vulnerabilities present indicators that highlight the vulnerability levels of different countries. Predictably (based on what we previously know), those living in poverty are particularly at risk. Despite the recent progress on poverty reduction, about one in four people still live in multidimensional poverty or are vulnerable to it, and more than 40% of people worldwide do not have access to any social protection.

This second set of data is again colour coded (low, medium and high levels of vulnerability) and regionally recorded making it particularly relevant and immediately usable. For students and teachers exploring human development, this second dashboard is especially illuminating and helpful. The shocking reality of inequality is graphically illustrated in this dashboard when we compare the two 3’s – the country with the third highest level of human development worldwide – Ireland with the 3rd lowest level – Chad.

Average per 10,000 people – 2010-2018

The pandemic highlights how disruptions in one place become contagious, triggering problems elsewhere. For example, economic slowdown and recession in richer countries negatively impacts on poorer countries dependent on emigrant remittances. A slowdown or collapse in tourism worldwide has significant consequences for poorer countries dependent on that sector.

The two sets of data can be accessed and downloaded free from UNDP.

Cape Town community leader Khanyisa Msengana notes that that long queues form at the three water taps in her local area at weekends.

‘I wait for an hour in a queue before I get one bucket of water to do laundry, cook and drink at weekends…If I use the one bucket of water to do laundry then I remain without water to cook and wash hands.’

The majority of Kenya’s labour force … live from hand to mouth and depend on a daily wage. Those in salaried employment do not have full benefits as they operate on contracts. Almost all of them are not in unions… The directive to work from home and self-isolate is impractical because it forces workers to choose between earning their daily bread or staying at home and starving. The situation is even more dire for those in rural areas who rely on selling their produce to towns and cities. But the closure of markets means potentially millions will not have the bus fare to go to health care facilities for treatment or the money to buy hand sanitiser and soap.’

Out of Control: Crisis, Covid-19 and Capitalism in Africa, Femi Aborisade, March 26, 2020, Review of African Political Economy

Social distancing is a privilege. It means you live in a house large enough to practice it. Hand washing is a privileged to. It means you have access to running water. Hand sanitisers are a privilege. It means you have money to buy them. Lockdowns are a privilege. It means you can afford to be at home. Most of the ways to ward the Corona off are accessible only to the affluent. In essence a disease that was spread by the rich, as they flew around the globe, will now kill millions of the poor. All of us who are practising social distancing and have imposed a lockdown on ourselves must appreciate how privileged we are. Many Indians won’t be able to do any of this.’

The view of an unnamed Indian doctor quoted The Daily Maverick, March 24, 2020

Kai Evans explores how governments used COVID-19 restrictions for the wrong reasons.

COVID-19 vaccine inequality remains, despite many of us returning to a form of ‘normality.’ Kai Evans finds out why.

Kai Evans reviews lessons learned from the pandemic about protecting civil society space during a crisis.

Copyright © 1999-2025 DevelopmentEducation.ie

Except where otherwise noted, text-based content on this website may be used in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-SA 4.0) license. Except where otherwise noted, images on this site are © the attributed photographer/artist/illustrator or representative agency. For information please refer to our Content Policy