This developmenteducation.ie 4-part series argues that any understanding of development which disregards the role of faith is lacking a key dimension for a substantial proportion, perhaps a majority, of humanity. But can we identify precisely what that key dimension offers which might otherwise be missing?

In this first part of the series John Dornan and Suzanne Bunniss explore what the value of religion or faith might be in addressing the major issues, challenges and stories we face in the 21st century?

“It is not an easy time for the adherents of traditional faiths, and it is not an easy time for anyone in the tempest of global changes and the erosion of old nationalist and cultural borders. But this erosion also allows for a freedom from the past and an openness to new forms of sharing, learning, doing and being in a borderless world… In the global square, we may all stay encamped, waiting for the promise of a different kind of world, for some time to come.”

– God in the Tumult of the Global Square,

Religion in Global Society, Juergensmeyer, Griego and Soboslai, 2015

In 1970, at the first World Conference of the Religions for Peace in Kyoto, Japan, delegates agreed the following declaration which goes some way to describing that dimension:

“As we sat down together facing the overriding issues of peace we discovered that the things which unite us are more important than the things which divide us. We found that we share:

- A conviction of the fundamental unity of the human family, of the equality and dignity of all human beings;

- A sense if the sacredness of the individual person and his conscience;

- A sense of the value of the human community;

- A recognition that might is not right, that human power is not self-sufficient and absolute;

- A belief that love, compassion, unselfishness and the force of inner truthfulness and of the spirit have ultimately greater power than hate, enmity and self-interest;

- A sense of obligation to stand on the side of the poor and the oppressed as against the rich and the oppressors;

- A profound hope that good will finally prevail.”

– Hans Kung, Global Responsibility, In Search of a New World Ethic, 1991.

While it could be argued that the above list is overly idealistic and focuses too much on specifically religious concerns, it nonetheless offers a useful starting point for debate. We offer the following as further ideas and reflections on the contribution of faith to the human development and sustainability agenda:

- Sense of identity and solidarity

As economic globalisation has progressed, increased communication and mobility between people has become not only possible, but for many a necessity. Many people have looked to traditional sources of identity to provide some sense of stability. While not without difficulties, religions are developing new forms of expression both appropriate to the world today and for remaining in contact with their origins (Juergensmeyer, p.115).

- Integral human development

Grounded in the principles of Catholic Social Teaching, IHD promotes the dignity of the human person, equality between every person and the common good of all people in the community. Development cannot be limited to economic or material well-being alone, but should include political, social, moral and spiritual aspects to be authentic and holistic.

- Motivation for humanitarian action

Working from shared core values of justice, respect for dignity and inclusion, can provide individuals and faith-based organisations with the moral commitment and compass to address major concerns and challenges to vulnerable groups in the global family.

- Hope

Religious faith offers adherents a vision of a better world. Often in the most challenging circumstances, faith groups can be found working among the poorest communities or tackling seemingly insurmountable problems.

“The future belongs to those who give the next generation reason to hope.” – Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, Jesuit priest and philosopher

- Education

Faith-based organisations place great emphasis on the importance of education so that people can become authors of their own development. Learning from others and about different perspectives on mutual concerns is a fundamental requirement for the development of a global ethic and spirituality respecting and valuing all members of global society.

- Presence

Religious groups are often present in the most remote and marginalised communities on the planet, prepared to work among the most excluded, where official government agencies are reluctant or unable to act.

“We just have to get out of bed and do whatever good deeds are to be done that day.” – Fr Timothy Radcliffe, former Master of the Dominican Order, public lecture, Glasgow, March 2019

- Experience

Historically, many campaigns have been built on the beliefs of faith groups, from the Wilberforce campaign for the abolition of slavery in the 19th century, through to the anti-apartheid campaign in South Africa, to the leadership provided by the Brazilian Pastoral Land Commission in the struggle against military dictatorship in Brazil in late 20th century. Perhaps most significant was the role played by churches in organising at local level during the civil rights campaign in the United States:

“The music and the religion provided a contact between our logic and our feelings… and gave the logic of what we were doing emotional and human power to make us go forward.” – Jean Wheeler Smith, civil rights activist, I’ve Got The Light of Freedom, The Organizing Tradition and the Mississippi Freedom Struggle, Charles M. Payne, 2007

In this learning unit we explore the following question – what is the value of religion or faith in addressing the major issues, challenges and stories we face in the 21st century?

In doing so we begin from our own Christian perspective without wanting to in any way limit or deny the value of insights to be gained from all the major world faiths. Wherever possible we try to ensure that those different perspectives speak for themselves and not through our interpretation.

As Gandhi noted, “The essence of all religions is one. Only their approaches are different.” If we are to make sense of our one world, then we also have to learn and practise dialogue, respecting the right of others to think and believe differently, with the underlying caveat that none of us has the right to cause harm to others through the practice of our own beliefs.

Faith, culture and dialogue

Attempting to engage in a dialogue between different cultures can be difficult at the best of times. Participants have different starting points, frames of reference, very different experience and often speak a different language, or use the same language in very different ways. Exploring the role of faith in development and justice will look very different for those from primarily secular contexts and others whose experience and perspectives are formed in a religious framework. It is also very possible that both sides may have at best little comprehension of the other ‘side’, or at worst, have had a very negative encounter with different perspectives. All of us have to co-exist in a world where our personal standpoint may be held by a minority of one.

Terms such as right and wrong, good and evil, or truth have been debated for centuries. Humanity is still grappling with the complexities of living in societies with numerous competing standpoints for living and, somewhere in our own evolution as a species, we found it useful to treat signs of difference as potentially dangerous. We need to move on.

A wise person once said where we disagree, we have something to learn from each other. The content offered here is intended to open space for a debate where everyone should seek to do just that – learn. We cannot hope in the space of a few pages to settle every question between different faiths or systems of belief, but we can hope that others will start here and take their own search further in learning to respect our differences without feeling compelled to accept or reject them without further examination.

1. Identifying some key principles

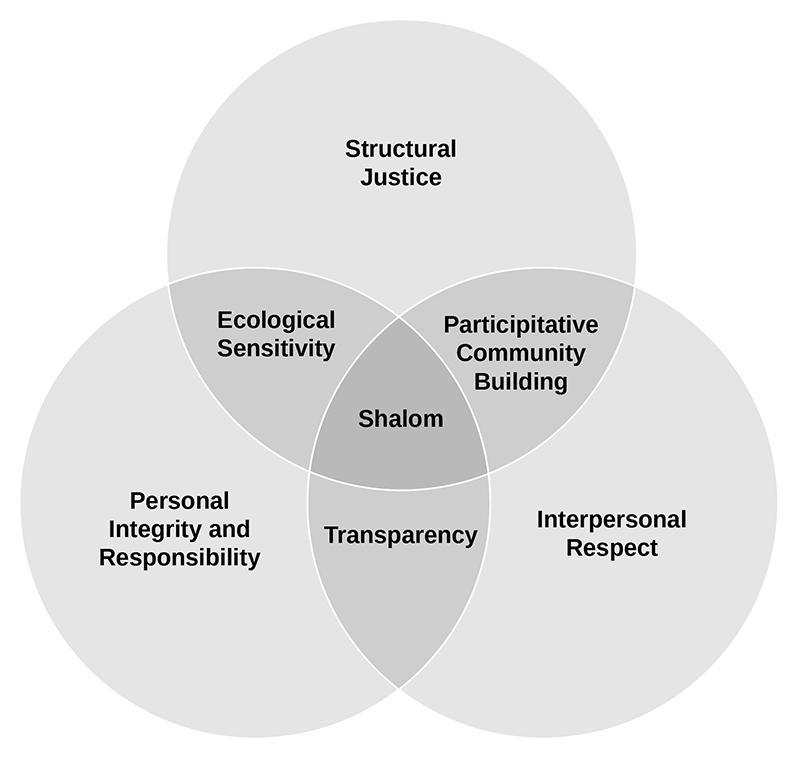

To help us in our exploration, we make use of a simple diagram used by Donal Dorr in his book, Integral Spirituality, Resources for Community, Justice, Peace and the Earth.

Dorr uses the overlapping circles to represent the different aspects to be considered when looking at any issue: the personal, the inter-personal and the public or structural. By taking into account the different aspects, we can try to see any issue holistically, recognising that there are different dimensions to achieve an effective outcome. What I do (or don’t do) has an effect on others; how we understand and respect alternative ways of looking at the issue; the context in which we make decisions and how this enhances or limits the effectiveness of our choices. Emphasising one area over others can reduce the impact of our actions and campaigns.

The areas of overlap also help us to identify where actions on different dimensions of the issue impact on the individual, others and wider society. The Biblical passage from the prophet Micah sums up the different aspects for consideration: “This is what Yahweh asks of you, only this: that you act justly, that you love tenderly, that you walk humbly with your God.” (Micah 6:8) The central area of overlap, Dorr designated to represent shalom, a Hebrew word signifying peace in every area of life.

Key principles for consideration can always be debated and those offered here can be added to or subtracted from in examining any specific issue and will frequently overlap, but are widely accepted as important:

- Dignity of the human person: in the social teaching of the Catholic Church, “it is not just a question of fighting wretched conditions, though this is an urgent and necessary task. It involves building a human community where all can live truly human lives, free from discrimination on account of race, religion or nationality, free from servitude to others or to natural forces which they cannot control satisfactorily.” (Pope Paul VI, 1967)

- Promotion of the common good: this refers to the sum total of all the conditions – economic, political and cultural – which make it possible for women and men to achieve their potential. It implies that every individual has a duty to share in promoting the welfare of the community as well as a right to benefit from that welfare.

- Global solidarity: recognising our common humanity irrespective of perceived differences of race, religion, gender, sexuality, political ideology or geographical location

- Promotion of peace: recognising that we must find more effective ways of resolving differences and conflicts without resorting to violence and use of weapons of indiscriminate and mass destruction of life.

- Stewardship: recognising that the resources of the earth are for the benefit of all people and to be used responsibly so as to ensure their continued enjoyment by future generations.

- Economic Justice: recognising that economic activity is the means by which we meet our needs and that workers take precedence over capital and technology, with the right to a just wage and to organise themselves.

- Political Participation: recognising that democratic participation is the best way to respect the dignity and liberty of all people.

- Option for the Poor: recognising that priority should be given to improving the situation of the poor, those who are economically disadvantaged by status, oppression and powerlessness.

- Link between religious and social dimensions of life: recognising that faith and justice are closely linked, that the social dimension of life is an integral part of a religious perspective and no aspect of life is excluded from faith.

- Link between love and justice: recognising that love of neighbour is a necessary element of promoting actions and structures which respect human dignity, protect human rights and enable human development.

When we look at any aspect of social and environmental justice or human rights, we are essentially faced with three questions:

- What is my personal responsibility in this?

- What is our responsibility to one another, especially to the most vulnerable?

- What needs to be put in place at local, national or global level to ensure the wellbeing of current and future generations?

In approaching issues of development, social justice and human rights from a faith perspective, the advice of Pope Paul VI, is worth consideration:

“… it belongs to the laity, without waiting passively for orders and directives, to take the initiative freely to infuse a Christian spirit into the mentality, customs, laws and structures of the community in which they live.”

On the Development of Peoples, 1967, §81

More recently, Pope Francis has also stated:

“I prefer a Church which is bruised, hurting and dirty because it has been out on the streets, rather than a Church which is unhealthy from being confined and from clinging to its own security. ”

The Joy of the Gospel, 2013, §49

And again:

While it is quite true that the essential vocation and mission of the lay faithful is to strive that earthly realities and all human activity may be transformed by the Gospel, none of us can think we are exempt from concern for the poor and for social justice…”

The Joy of the Gospel, 2013, §201

In each generation we need to find the motivation and inspiration to engage with the major challenges of our time. For many people, that motivation often comes from their religious faith.

About the series

This 4-part series explores three key issues – poverty and wealth, climate change and women’s rights – from an explicit faith perspective, and introduces a range of activities, links and resources for facilitating learning exercises and workshops.

The next part in the series asks, is wealth the problem? Take a look at other parts in the series: part 3. The Earth is our home; part 4. Women and development

- Suzanne Bunniss (PhD) is a social science researcher and charity director of FireCloud, based in Clydebank, Scotland.

- John Dornan has been a development education activist for over four decades and recently retired as project manager of global education at the Conforti Institute based in Coatbridge, Scotland.

- Note: this series has been developed with additional reporting, commentary and review by Colm Regan of developmenteducation.ie and Stephen Farley of Trócaire.