TheModern Slaveryseries

Modern Slavery: Joining the dots in the classroom

A young boy carries a large bag of recyclables while working in a public dump in Bangladesh (2012). Photo: by Zoriah via Flickr.com. Used under CC BY-NC 2.0.

- by Caitríona Ní Cassaithe and Ben Mallon

Slavery in the world today is seen as a criminal justice and security issue that mainly involves individuals in the global South, decoupled from structural and wider societal issues it is connected to. Does tackling modern slavery even come close to engaging with historical slavery and its legacies?

The Modern Slavery series is a three-part series. In part three, Caitríona Ní Cassaithe and Ben Mallon introduce a teacher’s guide and methods for exploring modern slavery today and addressing complex issues such as inequality, power and exploitation.

- For more in the series, see part one Joining the dots of inequality, power and exploitation and part two on the Brazilian ‘flying squad’, Guaraní land reform and the Coalition of Immokalee Workers.

While history education is often used to provide a context to the legacies of slavery, the historical connection to contemporary slavery is frequently overlooked in classroom practice.

Based on a review of the literature of slavery education in history, we found that history lessons on the subject are often chronologically, geographically and thematically limited and predominantly focus on the factual aspects of the transatlantic slave trade.

This bounded focus can lead to the exclusion or omission of other time spans and locations and this kind of narrow coverage can also contribute to forming misconceptions about slavery.

Two of the biggest of these misconceptions are that slavery only occurred within the transatlantic triangle in the continents of Africa and North America and, perhaps more worryingly, a belief that slavery ended with the abolition of slavery centuries ago.

Historical enquiry, when framed through the lens of Critical Development Education (CDE), can help students make connections between past and present forms of slavery, as well as its ongoing global legacies.

Additionally, this framing also allows for connections to be made to the didactic, affective and active domains that we argue must be stimulated in the teaching of such issues.

Introducing a framework for Critical Development Education

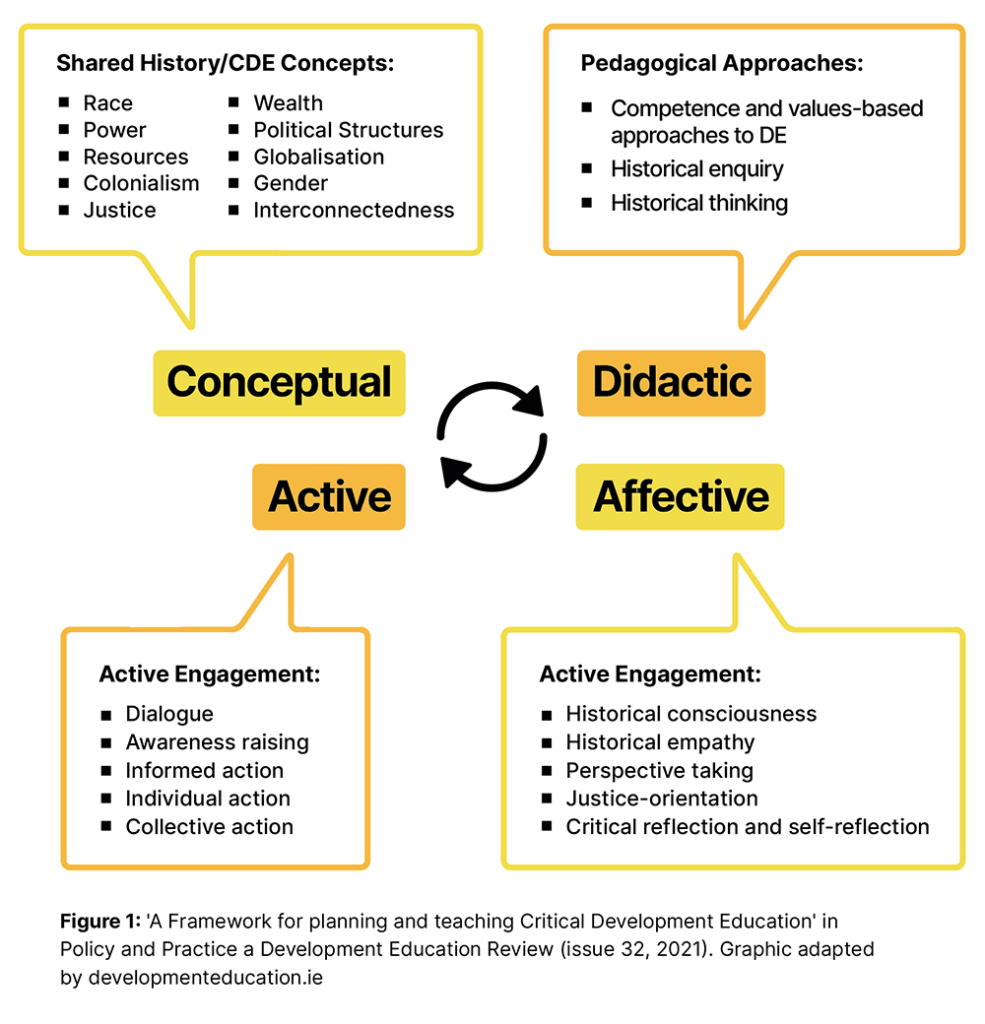

Comprised of four interrelated dimensions, the framework for Critical Development Education (CDE) identifies a series of key concepts to underpin an enquiry in this area.

These are the conceptual, didactic, affective and active dimensions (see the Figure 1: Framework below). In the following section, we explain each of these dimensions in further detail.

Conceptual

A number of studies show that students often have a weak understanding of the conceptual ideas they are dealing with.

While they may be familiar with examples of colonialism or racism in history, rarely are these concepts fully explored or understood, and they may still operate with weak definitions that have been learned off, poorly conceptualised or swiftly forgotten.

To address this, concepts must be carefully selected by the teacher and actively taught.

Affective

The affective aspect asks us to consider issues such as historical consciousness, which can be generally defined as the process by which people orient themselves in time; this orientation allows the individual to situate and direct themselves within a historical and temporal continuum in order to understand the past.

Understanding how the decisions people made in the past can impact on society today, and understanding that present actions will have implications for future generations is, as we argue, one of history education’s essential contributions to society.

Active

‘Active engagement’ requires teachers to think about the end product of the enquiry.

This may simply be providing space for dialogic discussions on the topic, or perhaps an awareness raising campaign or some sort of action, be that individual or collective.

Didactic

Similarly, the teacher needs to think about the pedagogical approaches that will be used to teach about these issues.

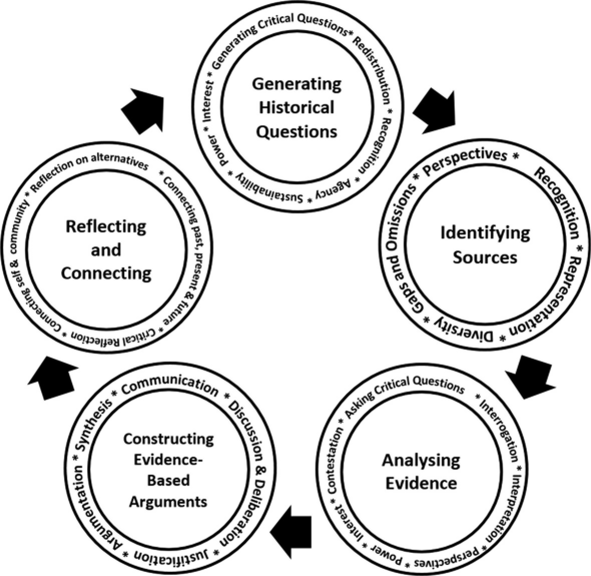

Rather than passive textbook exercises, students need active engagement. A key pedagogy in history education is historical enquiry.

Enquiry begins with asking a question, interrogating the evidence to answer that question, creating interpretations based on that interrogation, and connecting this interpretation to wider concerns (see figure 2 on historical inquiry for more).

Using the framework in the classroom

- The following section provides a brief exemplar of how the framework can be used in classrooms to explore the connections between contemporary and historic slavery.

- Suggested sources of evidence are highlighted and links to resources are provided (also available to download).

Background knowledge for educators

Bartolomé de las Casas’ life story is fascinating. He went to the Americas as a conqueror, had slaves and land, but gave them up because of what he saw; became an activist and even tried to form a nicer kind of colony in Venezuela, then entered the Dominican order and later was the driving force behind the limitation of the encomienda system that treated indigenous people as property.

So his life encompasses huge learnings and transformations, but also some missteps (for example, he called for indigenous slavery to be replaced by African slavery, a statement he later regretted and recanted, but worth considering in the exploration of the legacy of the man and slavery itself).

Students could use a pros and cons list throughout the series of lessons as they explore the evidence selected by the teacher to decide if de las Casas should be remembered (also developing historical interpretations and multiple perspectives).

1. Developing a concept map of slavery

What does slavery look like?

- In groups, students collect 5 images to represent slavery and explain why each image was chosen (note quietly if any student has selected modern slavery images)

- These are used to help students construct a concept map (Resource 2). Students then create their own personal working definition of the concept

2. Didactic

Main Enquiry Question: From Conquistador to Champion: Should we remember Bartolomé de las Casas?

Using an image of a statue of Bartolomé de las Casas as a stimulus (Resource 3), students create a list of questions which will form part of their enquiry into slavey. Teacher gathers evidence to help students answer these questions, for example:

- Reading extracts from his works – he wrote very influential accounts of the Conquests – students interrogate these whilst also developing historical thinking skills eg: creating a timeline of his life (time and chronology).

- Exploring accounts of the Conquests allows them to use historical evidence as a historian would. (read ebook A Brief Account of the Destruction of the Indies by Bartolomé de las Casas, 1552)

- Explore engravings of atrocities – multisensory explorations (imagine you are in this image, what can you see? Hear? Smell? Touch?) of the engravings (historical empathy). (some of these may be unsuitable for younger children).

- Reading selected accounts written by historians (historical interpretations) and using all these sources and their pro/cons list (Resource 4) to answer the original enquiry question and other questions they have generated.

- Considering broader questions of who is remembered and why? See the Zinn Education Project on ‘whose history matters?‘.

Resource 3: From Conquistador to Champion: Should we remember Bartolomé de las Casas?

Create a list of questions.

Resource 4:

From Conquistador to Champion: Should we remember Bartolomé de las Casas?

Make a list of:

| Pros | Cons |

|---|---|

3. Affective – making connections between past and present

Connecting statement: In one of his correspondences with the Emperor of Spain, De las Casas argued that laws alone would never be enough to end exploitation.

Students discuss this statement, what did he mean by this, why are laws not enough? What are the other issues that need to be addressed?

- Students are asked to consider whether slavery has ended or not.

- Students revisit Resource 2 and discuss the images they selected, paying particular attention to any modern images (if none are selected perhaps a good time for discussion about this).

4. Action

Enquiry Question: Are laws enough to end exploitation?

Although slavery has been legally abolished at international level as well as by almost all countries, how is it that an estimated 50 million people are considered to be in conditions of modern slavery today?

- Learners can investigate the 3 case studies on Brazilian ‘flying squad’, Guaraní land reform and the Coalition of Immokalee Workers (Resource 5) from the and discuss the above question to interrogate if and why modern slavery exists in these contexts.

- Learners could further explore these case studies using Geographic Information System (GIS) tools (e.g. Google Earth) to map related incidents, to make connections to other sources (e.g. newspaper articles or television reports) and add self-generated text video, and audio to visualise and explain the forms of action.

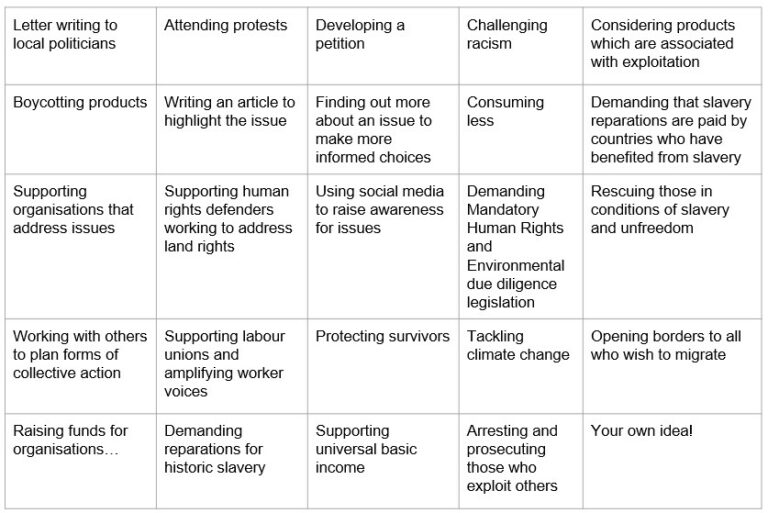

- Learners can also explore and discuss various forms of action that are taken to address slavery. This could take the form of a card sorting activity (see Resource 6 below) where learners discuss the pros and cons of different forms of action, which could include:

- individual actions, such as boycotting goods or services connected to exploitative working practices; letter writing to politicians

- collective actions, such as attending anti-slavery protests; working with organisations which seek to improve working rights;

- legal actions against modern slavery, such as arresting and prosecuting those who exploit others;

- global actions seeking to address the ongoing consequences of historical slavery, such as demanding that slavery reparations are paid by countries who have benefited from slavery.

- Students can add to their working definition of slavery incorporating new information about modern forms. This process can support learners to consider informed action(s) in response to the challenges they have defined and learned more about.

Resource 6: Card Sort

Download: access the modern slavery resources PPT presentation for onward use.

Note: This piece provides an overview of the methodology developed by the authors in collaboration with DCU colleagues, and published open access in the journal Policy and Practice: A Development Education Review in 2021, which considers how the issue of modern slavery and the concepts of inequality, power and exploitation can be explored in a classroom.

- Dr Caitríona Ní Cassaithe is an Assistant Professor in History Education in the School of STEM Education, Innovation & Global Studies in the Institute of Education, Dublin City University. Her research interests include: the learning and teaching of history at primary and post-primary level, initial teacher education, museum, heritage and place-based education, digital technologies, controversial/contested issues and disciplinary literacy.

- Dr Ben Mallon is Assistant Professor in Geography and Citizenship Education in the School of STEM Education, Innovation & Global Studies in the Institute of Education, Dublin City University. His research focuses on pedagogical approaches which address conflict, challenge violence and support the development of peaceful societies.

TheModern Slaveryseries

- Check out part one in the series on joining the dots of inequality, power and exploitation; and

- Part two introduces three stories from groups fighting back: Brazilian ‘flying squad’, Guaraní land reform and the Coalition of Immokalee Workers

The Method series features pedagogies and methods for the teacher & trainer’s toolbox.