TheModern Slaveryseries

Modern Slavery: Joining the dots of inequality, power and exploitation

Photo by Zoriah via Flickr.com. Used under CC BY-NC 2.0.

- by Chris O’Connell

Slavery in the world today is seen as a criminal justice and security issue that mainly involves individuals in the global South, decoupled from structural and wider societal issues it is connected to. Does tackling modern slavery even come close to engaging with historical slavery and its legacies?

The Modern Slavery series is a three-part series. In part one, Chris O’Connell explores how ‘modern slavery’ is mainly defined as a criminal justice issue yet instead should be read through power relations approaches and the inequalities they foster.

- For more in the series, see part 2 on the Brazilian ‘flying squad’, Guaraní land reform and the Coalition of Immokalee Workers and part 3 Joining the dots in the classroom.

Not long ago it was common to read headlines proclaiming that slavery “did not end with abolition”, or that it was “still with us”. No more. Tales of ‘modern slavery’ have become a regular staple of media exposés, some of them sensationalist. The variety of products and the range of locations involved attest to the global nature of highly exploitative labour practices: from prawns in Thailand to chocolate in the Ivory Coast; from cotton in Turkmenistan to gold in the Amazon; from cattle farming in Brazil to prison labour in the US, contemporary forms of slavery are both persistent and pervasive.

This includes Ireland, which has a poor record in this area, exemplified by revelations of chronic exploitation in the country’s €4 billion meat industry. Indeed, for two years to 2022 Ireland was the only Western European country placed on the ‘Tier 2 Watch List’ by the US State Department’s annual Trafficking in Persons (TiP) Report – indicating that the state had failed to meet the minimum standards and had not taken proportionate concrete action to address that failure. But this begs the question: what does effective action to combat exploitation and abuse look like?

While Ireland’s record is notably poor, much of what counts as ‘action’ under the TiP Report – or the more publicised but problematic Global Slavery Index – is highly questionable. In particular, the global tendency has been to conceive of trafficking and slavery as an individualised relationship between a ‘criminal slaveholder’ (in the parlance of influential scholar and activist, Kevin Bales) and victim, divorced from other contexts. Framed in this way, the problem suggests its own solution: prosecute the guilty and rescue the innocent.

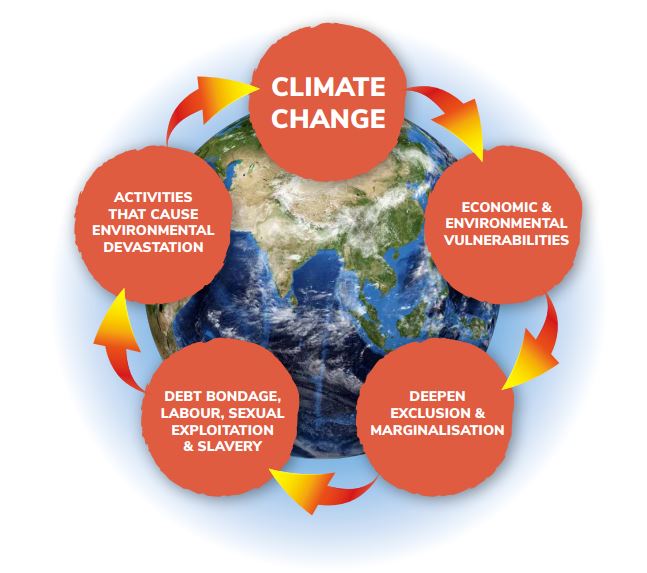

In reality, however, this approach to ‘modern slavery’ – even by its own limited criteria – is failing. Not only have global prosecution rates flatlined, but there is evidence that it has caused significant ‘collateral damage’ to victims. As this part one post in the series outlines, tackling ‘modern slavery’ requires a holistic, system-wide approach that recognises the fact that extreme forms of exploitation are rooted in unequal relations of power. This inequality assumes different, often mutually reinforcing, forms.

To achieve what social scientist Joel Quirk terms ‘effective emancipation’, it is necessary to go beyond the criminal justice approach to tackle unequal power relations.

Defining ‘Modern Slavery’: Everywhere and nowhere?

Extreme exploitation and abuse is an important global development issue. Under the guise of ‘modern slavery’, the issue has been incorporated into the UN Sustainable Development Goals (Target 8.7); championed by NGOS and states (particularly the UK); and used as an ‘umbrella’ term by the ILO to estimate that 50 million people are in conditions of forced labour, debt bondage, human trafficking and forced marriage worldwide.

Whilst the methodologies behind those figures have been questioned, in a two-part series on openDemocracy, there is little doubt that many people suffer degrading and exploitative conditions. Given the degree of human suffering, connections to broader development challenges, and links to global capitalism involved, this is an issue which educators should not ignore.

Nevertheless, it is a highly complex and contested one. Anti-Slavery International defines ‘modern slavery’ as ‘the severe exploitation of other people for personal or commercial gain’. While this definition may reflect commonly held intuition, it is difficult to operationalise in practice.

A complicating factor is that there is no internationally agreed definition of ‘modern slavery’. Instead, it acts as a catch-all term for different forms of human bondage already codified in international law – chattel slavery, forced labour, debt bondage, servitude, and servile marriage – along with human trafficking, which is viewed as a key route into exploitation. While all are defined international legal concepts, each one is open to interpretation.

Along with definitional issues, it is also worth considering the genesis of the current approach in the dual emergence of human trafficking, as set out in the 2000 Palermo Protocol (itself a product of concerns about migration and border control); and the ‘new’ slavery put forward by scholars like Kevin Bales in his book ‘Disposable People’. Both concepts understand exploitation as a relationship between individuals operating outside the global marketplace; as ‘anachronistic’ or ‘illicit’ practices.

Over time the ILO has followed suit: as legal scholar Prabha Kotiswaran notes, the ILO forced labour ‘indicators’ focus overwhelmingly on coercion by ‘force, threat and violence’. The result is a concept of ‘modern slavery’ that is expressly associated with ‘underdevelopment’ and criminality in the global South. It is this ‘cocooned’ or ‘sanitised’ approach that has found favour among national governments and international bodies.

This criminal justice approach has sparked a wealth of critical research and scholarship, however, drawing attention to problems with its framing and implementation. Among the critiques of this understanding of ‘modern slavery’ are that it:

- provides ‘cover’ for anti-feminist, anti-immigration and pro-business policies by states

- depoliticises the issue of labour exploitation, disempowers workers and lets business off the hook

- in spite of its invocation of the transatlantic slave trade, the modern slavery approach has been criticised as ahistorical. Particularly relevant is the critique that the dominant view fails to make links to global capitalism beyond vague references to a ‘dark underworld’.

Joining the Dots: Drivers of Vulnerability and Power

This oversight appears almost wilful: it is as if all the pieces of the puzzle are there, but there is hesitancy to assemble them. Or, to use another puzzle metaphor, there is no desire to join the dots. For example, Bales mentions the power of multinational corporations, but focuses his attention on individualised forms of oppression and solutions, like consumer power.

Similarly, a 2015 UN University report, Unshackling Development: Why we need a global partnership to end modern slavery, recognises that vulnerability is rooted in unequal power relations – ‘a form of extreme inequality, sustained by a range of vested interests’ – but frames these as aberrations, divorced from the normal functioning of a capitalist economy. The ILO does recognise that exploitation occurs along a continuum, but makes no serious attempt to place these ‘risk factors’ – poverty, gender, ethnicity, age, educational status – in any wider context.

By failing to engage with the social, economic, political and environmental drivers of vulnerability, the mainstream approach to ‘modern slavery’ serves to depoliticise what is, in the words of Kotiswaran and Sam Okyere, an ‘entirely political subject’. Other approaches, however, do exist – as the three stories featuring in part two next week will explore.

The key unifying factor of such alternatives is a challenge to the power structures that underpin vulnerability. However, for an issue to be a subject of political struggle, it must first be understood as such. The importance of this cognitive shift emphasises the role of education as a tool for liberation and contention.

In the remainder of this blog I suggest looking at key forms of power – economic, politico-legal, social and environmental – and their relevance to this issue.

Exploring 4 Types of Power Relations

Economic Power

Although typically framed as ‘poverty’, research reveals that what matters is not absolute but relative poverty and inequality. It is important to consider not only the assets available to an individual or household, but their ability to use them to subsist. Economic power speaks to the existence of dignified livelihood opportunities appropriate to the context.

Addressing imbalances could take the form of comprehensive social safety nets, land tenure, supply chain reform, or a system of ‘universal basic income’, for example. (Three stories illustrating the fight back against modern slavery are published in part 2 of The Modern Slavery series next Thursday).

Politico-Legal Power

Typically portrayed as the guarantor and enforcer of rights, in reality states are often involved in creating or worsening vulnerability to exploitation. This role can be active, such as forced labour in the cotton fields of Turkmenistan, or prison labour in the United States; or passive, such as failing to uphold labour rights, facilitate safe migration, or challenge corporate power. Migrant workers, for example, are frequently rendered vulnerable by their adverse incorporation into labour regimes.

In Ireland’s fishing industry, a Guardian exposé revealed trafficking and forced labour of migrants on trawlers.

In response, Ireland created a visa system that worsened their vulnerability, prompting an embarrassing rebuke from UN Special Rapporteurs and an ongoing legal challenge. Labour unions and other forms of collective power, such as social movements, have made inroads into addressing these imbalances (as part 2 in this series will illustrate).

Social Power

Within mainstream approaches to modern slavery, it is common to read that ‘anyone’ can be exploited (a recent Government of Ireland campaign is entitled ‘Anyone Trafficked’). This rhetoric obscures the role of social discrimination in casting some groups as ‘fit’ for exploitation. For example, in Brazil data gathered over many years reveals that most of the 54,000 people liberated by 2016 were black. Similarly, gender-based forms of discrimination underpin the systematic under-valuing of female work.

The obstacles erected to domestic worker organising to push through ILO Convention 189 illustrates the ongoing obstacles to equalising rights in that sector.

Environmental Power

A final consideration is environmental power. This relates to decisions about which areas and regions are considered fit to be ‘sacrificed’ in the name of national ‘development’. For the estimated two billion people connected to small farming, access to forests and water are key to their livelihoods and food security.

There is evidence that those impacted or displaced by environmental destruction and – increasingly – by the climate crisis, are vulnerable to exploitation and abuse. As the story of the Guaraní in Bolivia highlights, published in part two of this series next Thursday, indigenous demands for territorial control can reduce vulnerability to exploitation and protect the environment.

Modern slavery is an important issue for those interested in development education, but also a complex and contested one. In a recent issue of Policy and Practice: A Development Education journal, (issue 32 in Spring 2021) along with my colleagues Benjamin Mallon, Caitríona Ní Cassaithe and Maria Barry, we proposed a framework for teaching and learning about this issue. The framework seeks to persuade educators to focus on power relations and the inequalities they foster, which will be extended for part three in the last part of The Modern Slavery series.

As the Oxfam report Inequality Kills in Spring 2022 notes: “Extreme inequality is a form of ‘economic violence’”, that has its roots in legacies of racism, slavery and colonialism.

- Dr Chris O’Connell is a researcher at the School of Law and Government at Dublin City University and Project Officer at Comhlámh, the association of development workers and volunteers.

TheModern Slaveryseries

- Part two explores three stories that illustrate the fight back against slavery from the Brazilian anti-slavery system, the Guaraní in Bolivia and the Coalition of Immokalee Workers in Florida in the US in part two of The Modern Slavery series.

- Part three introduces a teacher’s guide and methods for exploring and addressing complexities in modern slavery today.