Scott Sinclair has been involved with Birmingham Development Education Centre and Tide~ Global Learning since it started and is a Tide~ trustee. Scott and his colleagues have planned and delivered numerous study visits locally in Birmingham, the UK and internationally over the past 40 years. As part of a three-part series of reflections to compliment our new guide to study visits and immersion programmes, we asked Scott to reflect on these experiences and to offer some advice to others planning such visits.

Study visits had a key role in the early strategy of the network that later became Tide~. [Teachers in development education] It is a complex matter driven by the need to learn from and about ‘the south’, understand development better and work on appropriate learning approaches. Study visits for teachers and other education practitioners also contributed to professional development and capacity building initiatives within the local education system. Tide~ also saw study visits as an opportunity to support others in taking a lead role in facilitating group learning. This we saw as a way of offering a higher-level professional development opportunity.

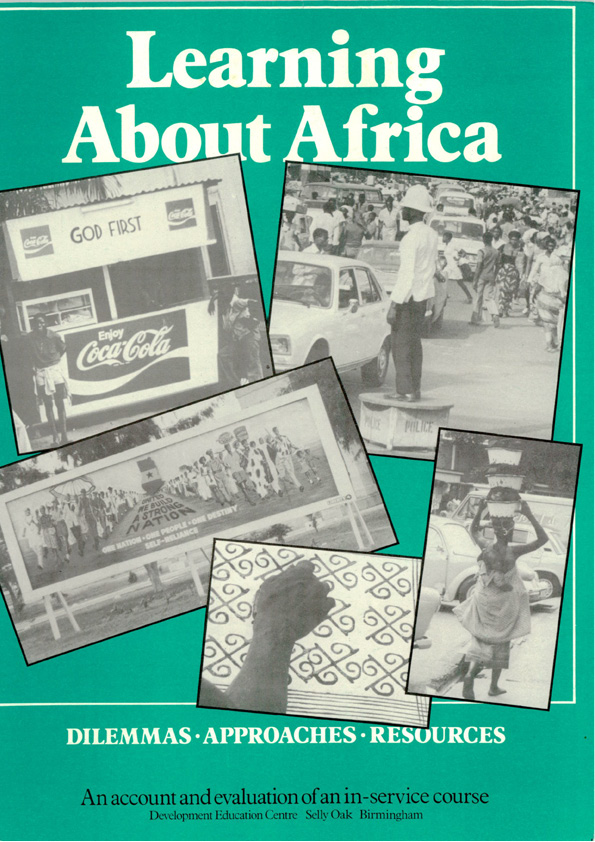

Study visits were not driven by an ‘education-aid’ mentality, in fact there was concern over the continued dominance of British perspectives on education (in, for example, Ghana); this was a key ‘development issue’ and one that we did not want to add to. Early work was also driven by the need to develop a pedagogy appropriate to an emerging concept of ‘development education’. A study visit to Ghana in 1977 produced an account of the visit and an evaluation of it as an ‘in-service course’. The resource Learning About Africa ~ dilemmas – approaches – resources offered a three-part model for the study visit that set the pattern for future work. This like other publications I mention can be viewed online or downloaded.

Study visits were not driven by an ‘education-aid’ mentality, in fact there was concern over the continued dominance of British perspectives on education (in, for example, Ghana); this was a key ‘development issue’ and one that we did not want to add to. Early work was also driven by the need to develop a pedagogy appropriate to an emerging concept of ‘development education’. A study visit to Ghana in 1977 produced an account of the visit and an evaluation of it as an ‘in-service course’. The resource Learning About Africa ~ dilemmas – approaches – resources offered a three-part model for the study visit that set the pattern for future work. This like other publications I mention can be viewed online or downloaded.

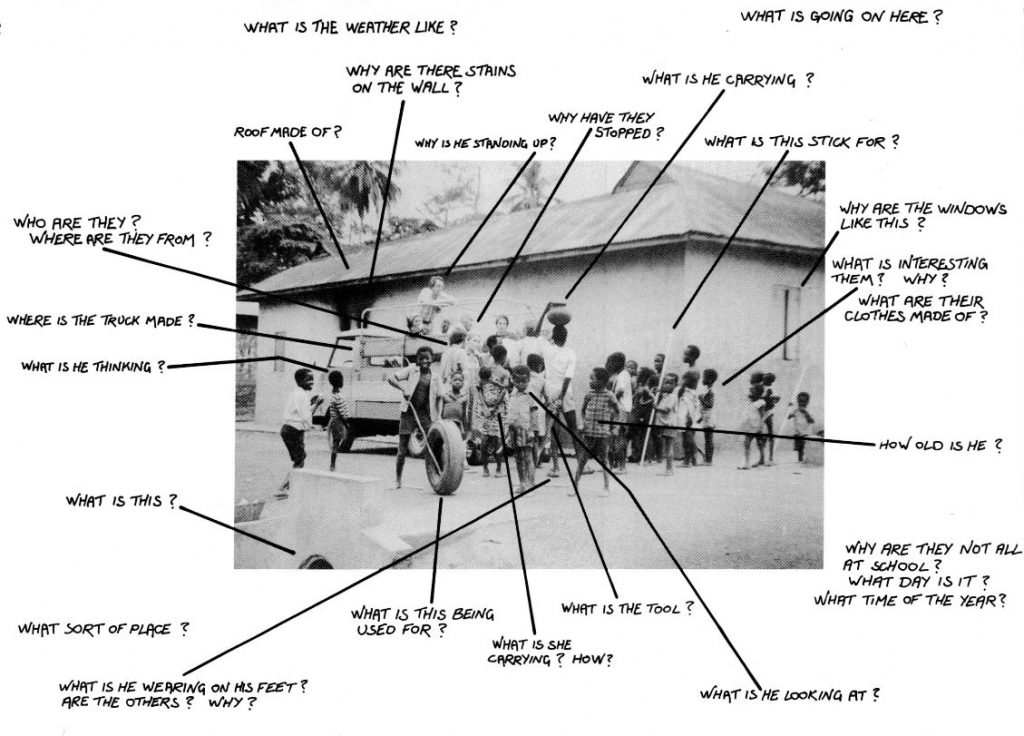

Preparation was seen as vital and included building skills for group learning, a focus on development themes in our own place (locally) and the need to think afresh about how our own learning through first-hand experience could shape our teaching ideas. Learning about Africa starts by highlighting challenges, for example:

- Could we identify the barriers to our own understanding of another country, its culture and its development?

- Would we be able to relate the way we cross those barriers through first-hand experience to methods we could use in our teaching, to enable our pupils to cross similar barriers?

Robin Richardson, who was then with the World Studies Trust, facilitated a preparation weekend that he wrote up in Learning about Africa. Follow up to the visit was also important for a wide range of reasons including network building and to enable creative thinking about the application of what had been learnt to work in the classroom.

Following this, Dorit Braun and myself wrote up the ‘model’ in the 1979 publication ‘Birmingham & the wider world ~ an in-service course, including a study visit, for Birmingham teachers’ [1979]. This featured a full course that involved work on Birmingham (a study visit to our own place) and then parallel visits to Columbia, Ghana and India. The follow up work produced a number of formative publications including Priorities for development ~a teachers handbook for development education’ (1981, second edition 1982) and the photo pack focused on development issues in Birmingham ‘The World in Birmingham ~ development as a local case study’. Birmingham (like any other ‘local’ place) offers the opportunity to encounter development and explore complex issues in their international context. This approach remains something that has not reached its potential in terms of the political literacy at the heart of development education and global learning.

Ireland also offered us a significant international partnership over the years (firstly through Trócaire and subsequently 80:20 Educating and Acting for a Better World). This partnership produced one of the first development education resources looking at the relationship between Ireland and the UK in 1986, titled: Half the lies are true – Ireland/Britain: a microcosm of international misunderstanding?. The resource highlighted the importance of images, perceptions, and identity in the development story. It now seems difficult (post the peace process) to realise just how much the public in both Ireland and England were able to ignore or set aside the fact that we had a major conflict/war going on locally. This work set the scene for a variety of creative work bringing teachers together from Ireland and England, sometimes focusing on local understanding, sometimes on joint work for example in Brazil. (See Fala Favela: photographs and activities on Shantytown life in Brazil by Trócaire, 1991).

Tide~ ideas about study visits evolved through partnerships involving Brazil, Columbia, Egypt, Ethiopia, Gambia, Ghana, Greece, India, Ireland, Japan, Kenya, Tanzania, South Africa, Taiwan, Uganda and Zambia. There was work of significance relating to each but some involved more than one initiative, others have had cumulative work over several years. All involved practitioners from Birmingham and the West Midlands in creative challenges about their own learning and appropriate teaching strategies. Many led to publications that both focused the group’s work and shared their ideas and experiences.

Three examples include:

- Whose development? – geographical issues in West Africa – from The Gambia and Senegal resulted from a study visit in 1986. A partnership with the National Environment Agency in Gambia and which led to a series of study visits over 30 years. This also included joint work with teachers in The Gambia for example the development of the publication Education for Sustainability.

- Work that included a partnership with Ghana’s Geographical Association. It involved 21 teachers from different parts of Ghana in a joint residential workshop and local fieldwork in Kumasi with Birmingham teachers. It led to the publication, Planning to teach about development issues ~ ideas from the Kumasi geography teachers’ workshop, 1995.

- South Africa provided the focus for several projects as the Tide~ network developed not least those linked to the two week visit to Birmingham by Desmond Tutu (see ‘Tutu ~ Preparation for Debate’ (1989). More recently Tide~ hosted 45 head-teachers from the Cape Town area for a two week study visit in Birmingham in 2005. Exploring Ubuntu: education and development was one of the outcomes of what we called the Ubuntu projects that included a study visit to South Africa for those involved in teacher education.

The study visit approach was demanding but proved to be an effective stimulus to more in depth teacher motivated professional development. It helped build professional networks and also enabled substantive partnership with teachers in other parts of the world — and often some joint work. Now there are more schemes for teachers to travel there seems to be more focus on schools. This can easily default to an aid model of the ‘expert visitor’ rather than the joint learning demanded by a study visit model.

The process is about supporting a group to work together in the context of another place, to enable them to meet people and engage with their ideas and concerns … and to think through the implications for both what they teach and, most significantly, how they do it in a way that enables students to experience similar quality learning. Offering ‘space’ for such teacher creativity is, I would argue, even more important today but it is in conflict with the more prescriptive approaches that have, for now, taken hold.

The projects were mostly very productive but the open ended nature of this study visit approach is risky. But providing ‘space’ for the creativity involved is not a luxury. It is vital if we are to really engage with the international issues that we face.

Finally, three key reflections:

- The first is about preparation. It is key to approaching the visit with an open mind and to building a ‘learning group’ that has purpose in terms of outcome but firstly makes the most of collective enquiry and the need to learn from the experience. Preparation is not just about knowing the issues and place before we go.

- The second is about process and the value of working with and/or learning from people in other places, seeking out different perspectives and engaging with the complexity and contradictions of development. A process that continues after the visit and reflects on similar complexity in our own place … and on the need to enable students to develop skills to explore such realities for themselves.

- The third is about synthesis and output. The value of the publications that were produced from Tide~ study visits was about sharing with others and offering useful resources. However the greater value was the focus this gave to group thinking, trialling ideas with learners and taking stock of what had been learnt.

Selected publications

- Learning about Africa ~ dilemmas, approaches, resources. An account and evaluation of an in-service course. DEC 1979. Birmingham & the wider world ~ An in-service course, including a study visit, for Birmingham teachers, 1979. DEC 1980 *

- Priorities for development ~a teacher’s handbook for development education, DEC 1981, Second Edition 1982.

- The world in Birmingham ~ development as a local case study. DEC 1982

- Half the Lies are True – Ireland/Britain: a microcosm of international misunderstanding? Trócaire & DEC 1986 *

- Fala Favela ~ photographs and activities on shantytown life in Brazil. Trocaire & DEC 1990

- Whose development? Geographical issues in West Africa- from The Gambia and Senegal. DEC in partnership with GA Ghana 1987 *

- Educating for sustainability ~ A resource for teachers of children aged 7-14 years. Tide~ and National Environment Agency Gambia 2002 *

- Planning to teach about development issues ~ ideas from the Kumasi geography teachers’ workshop DEC 1995 *

- Exploring Ubuntu – education and development: theories and debates. Tide~ 2005 *

* These publications can be reviewed or downloaded at tidegloballearning.net

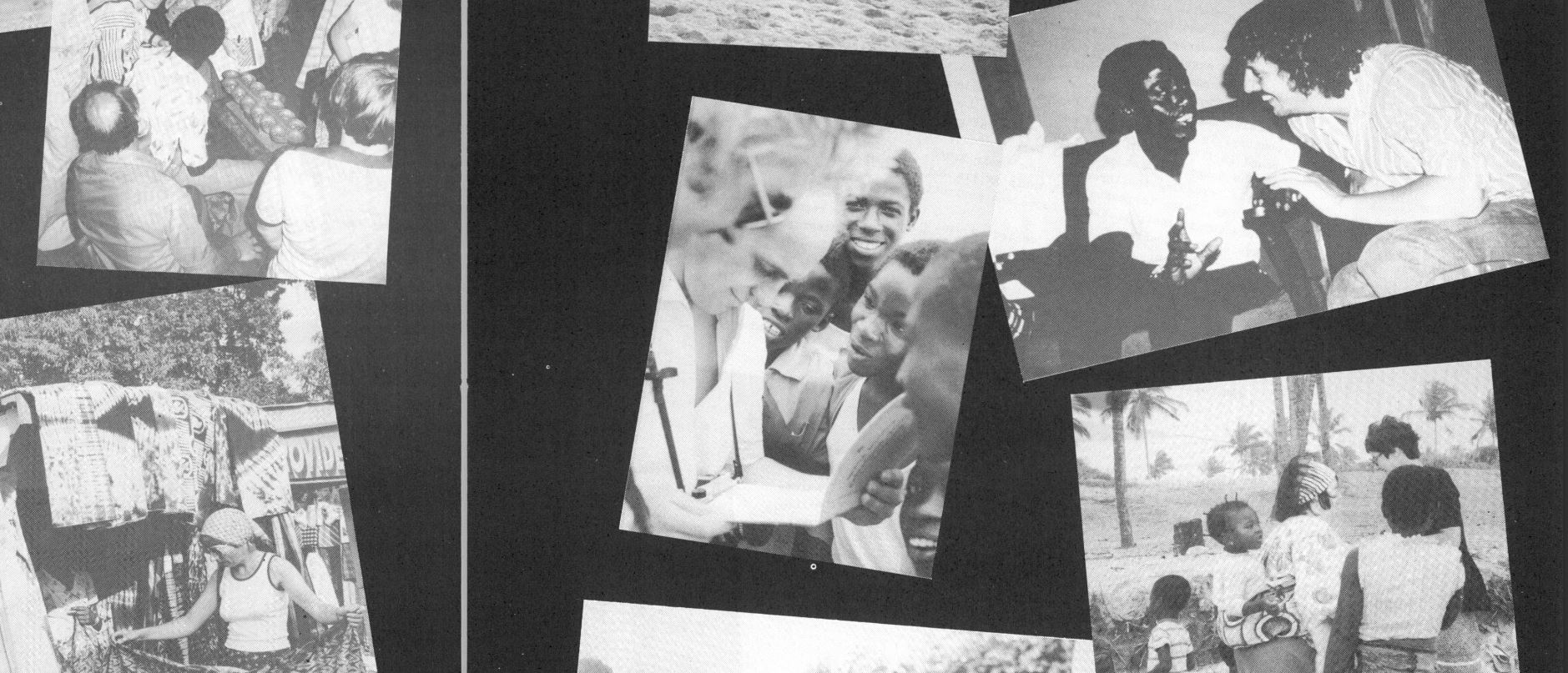

Featured image: photo collage of study visits programme to Ghana. Source: Learning from Africa by the Development Education Centre (DEC) Birmingham, 1977. (Pages 7 and 8)