Ten years ago the UN Development Programme reported that population growth and economic development would lead to nearly one in two people in Africa living in countries facing water scarcity or what is known as ‘water stress’ within 25 years.

That Africans could be sitting on a huge fresh water reservoir is desperately needed good news for the many millions of people who have lived through the effects of climate change, prolonged drought and stark weather fronts over the past 20 years.

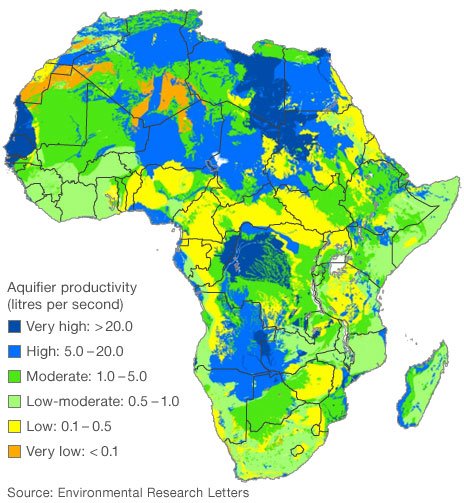

Scientists have for the first time been able to carry out a continent-wide analysis of the water that is hidden under the surface in aquifers. Researchers from the British Geological Survey and University College London (UCL) have mapped in detail the amount and potential yield of this groundwater resource across the continent.

Across Africa over 300 million people don’t have access to safe drinking water. The new findings show the volume of water available underground is 100 times the amount found on the surface – water which could be tapped to meet the need.

Large scale land acquisitions and commercial development projects have dominated the debate over ‘water wars’ and conflicts arising as a result of scarcity of resources. Transboundary water resources pose serious geopolitical problems. Water shortages contribute to conflicts of varying intensity and scale. Although these may appear localized, they have wider effects, such as displacement, mass migration, disruption of livelihoods, social breakdown and health risks, all of which leave their mark on the global community.

Millions of dispossessed famers and land workers have experienced the human dimension to this global problem for many years across Latin America, the Asia-Pacific and Africa as governments and corporations continue to ‘develop’ land and resources on a planet of scarcer resources:

Poorly regulated foreign investments in lands that could be otherwise used to feed local populations, could potentially have devastating consequences on the fragile state of food security at the national level.

UN World Water Development Report 4, p.216 (2012)

| Case Study: Water conflicts in Asia and the Pacific region

In the Asia-Pacific region water competition has led to increased water conflicts, particularly over the past two decades. Conflicts within countries have dominated since 1990, with more than 120,000 water-related disputes in China alone during this period. Water management efforts and resources in India often focus on ‘conflict management’ between different states. Direct conflict most commonly arises at the local level, and is often based on the construction of an ‘ill-thought-out’ dam, ambiguous water withdrawal rights or deteriorating water quality. The allocation of increasingly scarce water resources, however, is the principal cause of water conflicts, with the most important challenge in the region’s socioeconomic development being to balance different water uses and to manage their economic, social and environmental impacts. In water-stressed countries, there are competing demands for water for urban, industrial, agriculture and ecosystems upon which livelihoods depend. In addition, water disputes arise over inter-basin water transfers, which have environmental, social and financial challenges. Source: UN World Water Development Report 4, Volume 1. ‘Managing Water under Uncertainty and Risk’, p.194 (2012) |

While designed to be read on a regional or a continent-wide scale, the maps carry the caveat that they cannot be used for national planning, according to the report’s authors. As many aquifers are not being filled due to a lack of rain, the scientists have told BBC News that they are worried that large-scale borehole developments could rapidly deplete the resource.

Even if this is the case, the potential for fresh water reservoirs under the feet of most Africans is an incredible opportunity for the continent.

But important questions over the future and fallout of this new discovery will have real and lasting implications: Who will perform the extraction and how will it be managed? What methods will be used? Will they harm the local environment and local communities? What about beneficiaries – will they be local, regional or foreign? Will they mostly be large companies with the lions share of water being shipped out for sale on to foreign markets? What about environmental justice, distribution issues and the needs of Africans?

One has to wonder within the context of Africa’s recent history since the turn of the 20 century whether the abundance of maps, resources and foreign financiers have had a fair, even or positive long term impact for the peoples across its 56 countries (for example, see the Niger-Delta 1. & 2., Somalia and Sudan).

Will water become the new oil of Africa?

_______________________________________

Explore more…

- More information, debates and implications of these issues can be followed through our online module on Water & Sanitation.

- Who benefits from Africa’s oil? by Antony Goldman | BBC News | 9 March 2004

- Water: a fundamental human right or a commodity? by Shadrack Tjiramba | The Namibian | 07 August 2009

- Nigeria: subsidy report – A Looting Bazaar Uncovered by Edegbe Odemwingie | allAfrica | 21 April 2012