As part of our development debates series, Omar Grech investigates the facts, duties on states and the rising sensationalist language in Malta that is amplifying the most contentious public issue in recent years at the frontier of Europe’s borders: debating the rights of migrants and asylum seekers.

__________________________________________________________________

“We all came from refugees

Nobody simply just appeared,

Nobody’s here without a struggle,

And why should we live in fear

Of the weather or the troubles?

We all came here from somewhere.”

– We refugees by Benjamin Zephaniah (15 April, 1958)

“We can all be refugees” writes Benjamin Zephaniah, “Sometimes it only takes a day,…Sometimes it only takes a handshake…Or a paper that is signed.” Recently, the Prime Minister of the tiny Mediterranean island of Malta seems to have forgotten this simple fact. Malta is among the smallest member states of the European Union and the Council of Europe. . Malta has through its history seen successive waves of migrants from Phoenician traders through Roman warriors, Christian knights and British empire-builders. Malta has been built on both emigration and immigration. In the last few decades it has done well economically and prospered. But it has not always been so.

From the beginning of the 20th century until the 1970s Malta benefited from emigration mainly to Australia (over 1 million people claimed to be of Maltese descent in the 2001 census), Canada, the USA and the UK. Since the year 2002 Malta has started witnessing groups of sub-Saharan African persons seeking refuge in Malta either as asylum seekers or as economic migrants.

In the Maltese media the term illegal migrants and later irregular migrants started appearing ever more frequently. Xenophobic sentiments and downright racist comments started appearing with worrying and increasing regularity on social media and news websites. This was countered by a small group of NGOs who doggedly defended the rights of migrants, asylum-seekers and refugees.

In between these two positions, a majority of Maltese people seemed caught between worrying that Malta was too small to deal with an influx of migrants while at the same time understanding that these migrants and refugees were victims rather than criminals. The Maltese authorities have constantly appealed to the EU and EU member states to assist Malta in dealing with this issue. The response was slow and somewhat muted although a number of measures were undertaken to help Malta. Outside the EU, a number of states also assisted Malta. The USA in particular has accepted to give shelter to groups of refugees on a regular basis.

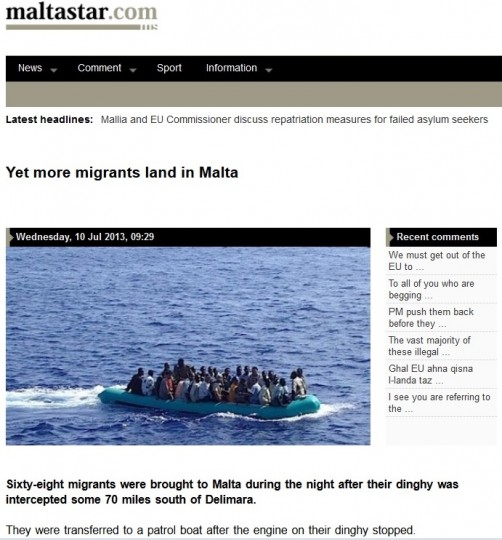

Sliding away the human rights of everyone for the “all options” imperative

In July 2013 the annual summer traffic of boats carrying migrants and asylum-seekers across the Mediterranean towards Europe resumed. The newly elected Maltese Prime Minister stated that he was unhappy with the lack of cooperation from the EU with regard to migrants and refugees and that he would be considering “all options” in dealing with this matter. When around a hundred migrants and asylum seekers landed in Malta on the 8th and 9th July the Prime Minister stated that he would be willing to forcibly return the migrants and asylum seekers to Libya. In the event, a group of Maltese NGOs filed an urgent application to the European Court of Human Rights which speedily issued an interim order prohibiting Malta from doing so. This event has pushed the issue of migration, refugees, racism and xenophobia to the forefront of Maltese public debate.

The debate in Malta over migrants and refugees has mainly revolved around misconceptions, dubious numbers and legitimate concerns. The major misconception concerns the definition of refugees.

The Maltese public has generally equated anyone arriving in Malta without a visa or required documentation with illegal migration. This is plainly wrong. A substantial number of those arriving in Malta have claimed the status of refugee. Someone claiming such a status upon entering Maltese territory may not be considered as having an illegal status. A person who claims asylum is, under the 1951 Refugee Convention (to which Malta is a party), entitled to be treated as an asylum-seeker until a competent tribunal finally decides on his/her status. If the competent tribunal determines that the asylum seeker qualifies as a refugee in terms of the Convention, then that person has a number of rights under international law. The Convention defines a refugee any person who is

“outside their country of origin and unable or unwilling to return there or to avail themselves of its protection, on account of a well-founded fear of persecution for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular group, or political opinion.”

This is an important definition. I am particularly struck by the word ‘persecution’. We should never lose sight of this essential fact. Refugees are fleeing from persecution: violence, torture, oppression, abuse and ill treatment.

Apart from defining who qualifies as a refugee, the Convention also establishes a key principle of international refugee law: the principle of ‘non-refoulement’. This simply means that it is illegal to send asylum-seekers back to the country they are escaping from. This principle includes three basic rules:

1. Not returning asylum seekers or refugees to a place where their life or liberty would be at risk;

2. Not preventing asylum seekers or refugees—even if they are being smuggled or trafficked—from seeking safety in a country, if there is a chance of them being returned to a country where their life or liberty would be at risk;

3. Not denying access to their territory to people fleeing persecution who have arrived at their border. (Here’s a 3 page reference sheet expanding on non-refoulement and protecting refugees from trafficking)

The European Court of Human Rights to which Malta is a party, together with all the other states who are members of the Council of Europe, has held that this principle can never be derogated from. Breaching such a rule is a breach of human rights. The fact that the Maltese Prime Minister was willing to countenance such a measure is a matter of great concern for two reasons.

Firstly, willingness to breach human rights by governments is, in itself, extremely worrying. The UN always characterises human rights as being universal, indivisible and inalienable. They belong to everyone equally and no one can be deprived of them. That a European government publicly expresses its intention to disregard them (for whatever reason) should concern everyone but especially the Maltese people first and foremost.

Secondly, rules of international law (including human rights rules) are of particular importance to small states. The USA with its military might and economic power has enough protection through self-help. Tiny states such as Malta have only the rules of international law to protect them. If Malta itself expresses a willingness to set aside rules which it finds inconvenient, it may live to regret it. Others may do so too in our regard.

Inflaming the numbers

A separate issue in Malta is that of numbers. Most Maltese people seem to think that there are many thousands of migrants and refugees in Malta.

The news media has played a significant role in creating this perception. Each arrival of a migrant boat is ‘greeted’ with headlines (usually on the front page) while when groups of migrants or refugees are relocated to a third country (such as the USA) the news is on page 6 next to the advert for air-conditioning.

UN estimates show that in February 2013 the number of arrivals still in Malta was around 5,000. In proportion to its size this is still a significant figure but certainly far from being a great emergency. The total immigrant population of migrants and refugees from sub-Saharan Africa that have stayed in Malta since 2003 thus amounts to slightly more than 1% of Malta’s population. Notions of ‘invasion’ used by some are utter nonsense.

This does not mean that the Maltese people have no legitimate concerns. Until very recently Malta was a generally homogenous society in terms of religion, culture and skin colour. The arrival of visible numbers of persons who look, talk and believe differently necessarily has an impact on Maltese people who were simply not used to it. This is especially the case for those communities where the migrants and refugees settle in comparatively larger numbers. Malta has a problem of space. By some accounts it is the second most densely populated country in Europe and one of the most densely populated in the world. Thus its capacity to absorb migrants and refugees is limited. Given the fact that Malta was not a country were migrants and refugees settled (at least since the 1900s) it was initially ill-equipped to deal with even comparatively modest inflows of asylum seekers and migrants.

A voluntary responsibility sharing scheme is currently in place where EU countries can voluntarily host protected refugees from Malta. Heated debates over the scheme’s success occur in arrangements of voluntary versus compulsory type schemes, with many in Malta calling for a move to the latter.

Having said all of this, the appropriate response to these and other legitimate concerns is not to fan the flames with populist patter. Condescendingly ignoring these concerns is equally inappropriate. A reasonable and reasoned discussion which dispels misconception, clarifies the issues and allows for the expression of legitimate concerns seems to me a more appropriate response. The Maltese government and the EU must also give the required assurances and responses to concerns that need to be addressed.

My concluding reflection concerns what this debate around migration and refugees says about us as Maltese in the 21st century. Malta has traditionally prided itself as being a welcoming, hospitable, warm-hearted country. The Maltese often quote with great pleasure an ancient instance of their kindness:

“When we had escaped, they learned that the island was called Malta. The natives showed us uncommon kindness; for they kindled a fire, and received us all, because of the present rain, and because of the cold.” (Acts 28:1-2)

Unsurprisingly this is a Biblical reference. Malta was, and to a large extent remains (at least formally), a staunchly Catholic country. And yet over the past decade the idea of Christian charity has not been at the forefront of the debate on migration and refugees. It seems that Christian charity and kindness only extend to those who share our same religious belief or skin colour or membership of the EU – as one example, see this recent article about Mata’s growing Swedish community in popular magazine Malta Inside Out). Pope Francis, who as the head of the Catholic Church should have some resonance with the vast majority of the Maltese population, a few weeks ago visited the island of Lampedusa to pray and reflect on the issue of migration, in particular praying for the many who die in the dangerous boat crossings. The Pope stated:

“These, our brothers and sisters seek to leave difficult situations in order to find a little serenity and peace, they seek a better place for themselves and for their families- but they found death… But God asks each one of us: “Where is the blood of your brother that cries out to me?” Today no one in the world feels responsible for this; we have lost the sense of fraternal responsibility.”

In Malta these questions have a special salience. What does it mean to be a Maltese today? Have we lost our sense of hospitality, kindness or charity? Or have we really never practiced these virtues beyond our immediate family, community or island?

Another question relates to the issue of our duties as Maltese citizens. Do we have any duties towards ‘others’ as citizens of a peaceful, prosperous European country that has succeeded through its own hard work but also through European assistance and through the benefits that accrued to us by being members of the international community? These are not questions that have been asked, debated or answered to any significant degree. The arrivals of “these our brothers and sisters” is an opportunity to start doing so.

In answering these questions consider again the words of Benjamin Zephaniah: we all came from refugees, didn’t we?