Gina Dorso presents a 5-point guide to decolonising aid based on an essential and wide reaching report that will be of interest to educators, policymakers, journalists and everyone working in the overseas aid industry, published by Peace Direct earlier this year, Time to Decolonise Aid: Insights and Lessons from a Global Consultation.

Discussions about unequal power dynamics in the international aid system have entered the mainstream, local activists have become increasingly vocal about the ways in which power and resources in the system remain dominated by, and between, certain organisations and relationships largely based in the Global North. It states that, despite the commitments to address the inequities in the system, most notably announced at the World Humanitarian Summit in Istanbul in 2016, little progress has been made in many key areas, including in the funding for local organisations and the way that decisions, power and control is still held by a relatively small number of donors and INGOs.

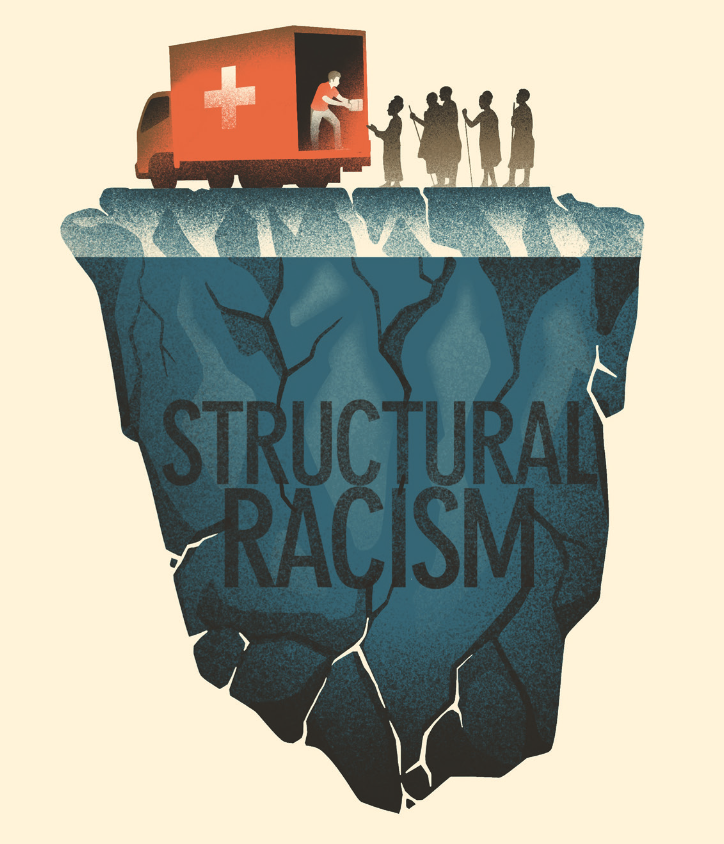

The report asserts that following the Black Lives Matter protests that evolved into a global movement in the summer of 2020, those working in the aid sector have been forced to confront the reality that their own work is steeped in structural racism, something which has been barely discussed or acknowledged until very recently.

Decolonising development, humanitarian aid and peacebuilding – the movement to address and dismantle racist and discriminatory structures and norms that are hidden in plain sight in the aid system – is emerging as an urgent, vital and long overdue discussion which adds greater weight to the existing calls to transform the system. If policymakers, donors, practitioners, academics and activists do not begin to address structural racism and what it means to decolonise aid, the system may never be able to transform itself in ways that truly shift power and resources to local actors.

This comprehensive 56-page report outlined the key findings from a global discussion on November 2020 that included over 150 activists, academics, journalists and peace and aid practitioners across six continents and 49 countries.

Here are some key takeaways from the report.

The report focused on a couple of key terms. Let’s start by unpacking those.

(Definitions taken from the report)

Structural Racism: (also known as systemic or institutional racism) a system of structures that have procedures or processes that disadvantage individuals or groups on the basis of their membership of a particular racial or ethnic group.

Decolonisation: Originally referred to the process of a state withdrawing from a former colony, leaving it independent.

White Gaze: a process where people and societies are viewed under the scope of white ethnocentrism, which assumes that whiteness is the only referent of progress.

White Saviour: refers to a complex where a white person provides help to non- white people in a self-serving manner.

The concept of “decolonising aid” has come up a lot in recent years. What does it mean and why is it seen as controversial?

People who are critical of the calls for ‘decolonising of aid’ say that they do not see aid as a colonial policy because it is often seen as doing something helpful, but the process of aid and the practices of colonialism are more similar than people might initially think. Participants said that the aid system, international NGOs, and academia often privilege White voices which reproduces the colonial practice of ‘White’ and ‘Western’ being seen as the most important and at the top of the social pyramid.

Why do people want to decolonise aid?

A criticism of the aid system is that more often than not, it perceives non-White, non-Western individuals as in need of its assistance. International NGOs and donors often set the project guidelines and determine what is worthy of funding. Some participants said that they would need to cater to their programs and ideas to receive necessary funds for their organisations. Decolonising aid calls for deconstructing colonial ideas regarding the superiority and privilege of Western thought and approaches. Participant Dany Tiwa said that

decolonising aid means that the focus should be on what people identify themselves as important. What we have noticed is issues that receive attention from aid donors are often more important for them than for the beneficiaries.

How do we decolonise aid? Recommendations for INGOs, donors and individuals

1. Acknowledge and Re-evaluate

According to the report, to decolonise aid, development, and peace-building, there is a lot of work to be done. But one of the first and most crucial steps is to acknowledge that these practices exist. Acknowledge that structural racism, unconscious bias, and stereotypes exist in your work. We all share the collective duty of acknowledging the problem so that it can be addressed properly.

Personal reflection is also very important. Reflect on why you wanted to get into this work and acknowledge the ways in which you are privileged by it.

2. Keep an Open Dialogue

Encourage a dialogue internally and externally that is open to critique, to ensure that different opinions and experiences are given space.

Encourage conversations about the power dynamics, hiring practices and transition. After acknowledging the structural racism that exists in your organisation, it is critical to take concrete steps to address and change. Keep an open dialogue with community and indigenous leaders. Participant Lorianna McAdams stated that:

To decolonise, donors, local partners and participating community agree on how the success of the project will be measured, what will be needed to demonstrate that, and allowing for that to change over time as the community learns and evolves.

3. Stop Certain Practices

Stop White Gaze Fundraising! It is time to end the practice of using images and language that diminishes the agency and dignity of communities that is aiming to serve in its fundraising materials. Organisations should be aware of practices of the ‘white savior’ complex in donors and in organisational leadership.

4. Shift of Power/Allowing for Change

Shift power to the local communities in which your work is aiming to help. Organisations should be adopting a transition mindset, which includes clear steps for the transfer of power. Rather than expanding reach INGOs should be looking at ways in which they can assist local organisations and remove their organisational ‘footprint’.

5. Have Courage

What this report highlights well is that breaking away from the status quo, especially a status quo that privileges you or privileges your organisation is difficult, but it is critical.

Have the courage to recruit and fund differently. Be willing to actively shift your power to non-White and non-Western local organisations. Have courage to actively create a space for change.

- Gina Dorso is a masters student in international peace studies in Trinity College Dublin, originally from New York.

- Illustrations credits: all illustrations were produced by Nash Weerasekera/The Jacky Winter Group, included in the Decolonising Aid report.

More blogs on developmenteducation.ie

From Nicaragua to Ireland: Fairtrade Coffee and Global Solidarity

Fátima Ismael of Soppexcca, Cathal Murphy from Bewley’s and Fairtrade practitioner Kieran Durnien discuss 20 years of Fairtrade coffee solidarity linking Nicaragua and Ireland.

Critical Thinking for Global Citizenship Education

Join Brighid Golden for the launch of her latest book, ‘Critical Thinking for Global Citizenship Education: A Conceptual Framework’

Your voice matters – 2026 user survey open

It’s January, its 2026, and we want to hear what you’d like us to feature or work on in 2026.

Calling Post Primary Teachers – Survey Participation Request

Your voice is vital in shaping the future of education for sustainable development in Ireland. Join a national survey for post primary teachers in October, led by DCU researcher Valerie Lewis

Webinar: Science for development on World Food Day

The webinar will feature YSTE projects, from Santa Sabina Dominican College (Dublin), Moate Community School (Westmeath) and CBS Thurles that focussed on nutrition and better food production, with Self Help Africa’s nutrition and gender specialist in Ethiopia, Sara Demissew.

Student & teacher webinar: Food, hunger and SDG 2

Join the World Food Day webinar for post primary school students and teachers which will explore SDG 2: Zero Hunger.