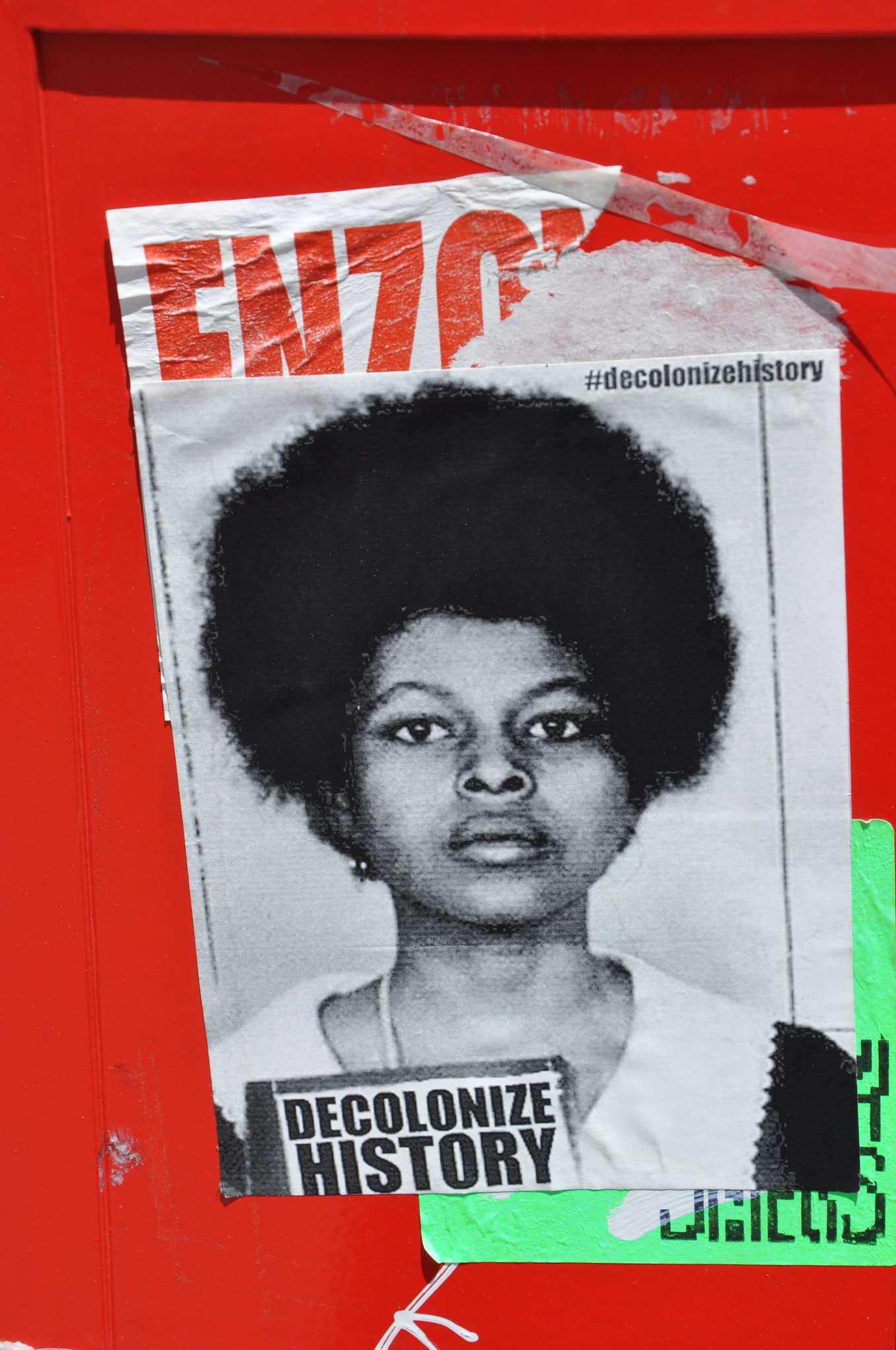

Decolonise History poster of US Black Liberation activist and Black Panther member Assata Shakur who was convicted of killing a police officer in 1977, only to escape prison two years later and become a political refugee in Cuba. Photo by wondercaty in 2014 via Flickr (CC-BY-2.0)

How might education practitioners begin journeys to decolonise how they teach and explore global issues? Niffy Olamiju reports on a workshop organised by the Irish Development Education Association in May 2022. (Update: part 2)

The ‘decolonising development education’ workshop is two-part workshop exercise organised for development education/global citizenship practitioners to explore new ways of approaching dev-ed from outside a Euro-centric lens in a three-way collaboration between IDEA (Irish Development Education Association), Comhlámh and Worldwise Global Schools. The sessions are led by experienced practitioners Sive Bresnihan (Comhlámh) and Lizzy Noone (WorldWise Global Schools).

Decolonising can be understood as the process of unravelling colonial practices. Within the education sector this looks like changing mindsets and taking a more intersectional approach to our teaching and learning.Part of this includes the seeking out and acceptance of knowledge from marginalised groups such those of the global south or indigenous educators.

The idea of ‘decolonising’ development education has been around for a while and has only become more pronounced following the pandemic as the structural inequities and injustices of our current system became more and more pronounced. I personally found the concept a bit complicated at first but decolonising simply refers to the process of undoing colonial ways of being, thinking and interacting with our world.

Decolonise vs Decoloniality… What’s the difference?

To be more specific when people speak of ‘decolonising’ they are more than often referring to ‘decoloniality’. which in the words of sociologist Aniba Quijano is “a perspective, stance and proposition of thought, analysis, sensing, making, doing, feeling and being that is actional, praxisitical and continuing’. (Simple isn’t it?)

Colonialism is the practice of one country having some form of political control and exploiting another country. Is it by nature an exploitative and cruel practice. Perfectly crafted to ensure that the mindsets and legacy of the practice (coloniality) extend far beyond independence days and continue to influence us all hundreds of years later.

Decoloniality aims to undo this influence and is an ongoing process of trying to challenge and see beyond our realities.

The workshops were aimed at challenging the colonial mindsets that guide our understanding of development education content and practice.

Employing different decolonial approaches such as deep reflection, silent creativity and reflective walks participants were able to gain a better idea of how they can also deliver a more transformative and impactful development education experience for learners.

Session notes

- Participants: Educators, facilitators and others involved in the development education sector

- Timeframe: 2 full workshops Tuesday 31 May and Tuesday 30 August, 2021

- In addition, there was also a separate at-home activity to be completed between workshops with a partner.

3 key takeaways

1. Reconnect with what drives you

Often we can get so caught up in work, life and all our other expectations and responsibilities that we forget how to see past what’s going on in our heads. As indigenous educators observe, our colonial mindsets have removed us from our surroundings. Ask yourself what sets the fire in your belly? What does transformative education look like to you?

2. The house that Modernity Built

Once we (as a society) began to modernise we first began by separating ourselves from the earth. This separation then made it easier to build a system which was based on exclusion, violence and inequity. The issue with this house is that it boxes us into its ideals and dulls our senses. We find it difficult to experience life outside of the rules and regulations set out by the house and instead seek temporary fixes or blissful ignorance.

3. Be open to diverse perspectives

Despite calls for decolonisation being around for a while, there is still a large gap in the field of information and methodology from non-western sources. This workshop relied heavily on teachings and concepts drawn from the Latin American Indigenous Community.

Memorable moments

The workshop started off with an invitation to leave our brains at the door and open our bodies and minds.

Starting the day by leaving all responsibilities behind us and underlying ‘agendas’ was a strong start because you immediately became more engaged in the workshop as an individual rather than as a member of an organisation, facilitator, parent or otherwise. I found this particularly helpful coming into the workshop because as an intern with little (or no) experience of the sector, imposter syndrome would definitely have left me silent out of fear of embarrassing myself due to a lack of knowledge.

Then we walked through the corn-on-the-cob metaphor.

If you closed your eyes and imagined a barn full of corn, what would it look like?

Most of us came back with pictures of long straight corn cobs with yellow husks all lined up neatly in rows.

In reality that’s only one variety of (genetically modified) corn. But in reality, Peruvian corn (where the crop originated from) comes in a variety of colours, shapes and sizes.

This exercise resonated with me the most because it shows how conditioned our thinking can become. We are so ingrained in our modern post-colonial mindsets that even as DevEd practitioners it was difficult to push past the desire to order the world and see past what we have been conditioned to believe is “right”.

The activity which brought the most complex feelings was the city walk.

Here, we were invited to calculate two numbers: the number of slaves (including modern slavery) as part of your own slavery footprint and the number of earths involved in maintaining our lives.

The number of slaves was particularly jarring because even despite my best efforts to live sustainably it was difficult to separate myself from a system which is built on violence, greed and exploitation.

While walking with our numbers we were encouraged to pay particular attention to our reactions. What emotions did we feel, how did our bodies react, any distractions, and so on? There were feelings of guilt, realisation, disgust, hopelessness and either the desire for a quick fix or a distraction.

Ultimately, we felt the gravity of the situation: how the world as we know it now has been strategically designed to benefit very few at the expense of the many.

We may feel that this fight is, at times, futile, but decolonizing our minds and education practices reminds us that just as these ideas were implemented they can be broken down. Rather than succumb to the present or lament the past we fuse the two to build a whole new future.

With new methodologies and approaches such as postitionality that overcome the challenges of modernity and allow us to move forward and learn in a manner which serves both people and planet.

“Positionality is the notion that personal values, views, and location in time and space influence how one understands the world. In this context, gender, race, class, and other aspects of identities are indicators of social and spatial positions and are not fixed, given qualities. Positions act on the knowledge a person has about things, both material and abstract.

Consequently, knowledge is the product of a specific position that reflects particular places and spaces.”

–Luis Sánchez, Positionality (entry in Encyclopedia of Geography)

- Update: check out the methods note on pedagogies of positionality and world travelling that is part 2 of this workshop report.

Niffy Olamiju is currently studying for her masters in International Relations at UCD and is an editorial intern at 80:20 Educating and Acting for a Better World.