Coffee harvesting experience in Masaka as part of an Aidlink immersion visit, Uganda, with Lana from St. Joseph’s, Rush, and Angel Farmer from Caritas Maddo. Photo: Aidlink, June 2019.

Study visits have been a staple in educational interventions on international development issues and contexts for many decades here in Ireland and also in the UK and internationally. Colm Regan introduces the guide and explores many of the issues involved in such study visits; it offers practical suggestions and ideas for organising them as well as for reflecting on them. It is based on the experience and practice of a wide range of organisations and has emerged from a series of individual projects as well as broader discussions and debates over several years.

This study visits and immersions programmes guide has been developed in partnership with Irish NGO Aidlink (many thanks to Anne Cleary in this context). Special thanks are due to Scott Sinclair and TIDE~Global Learning for key parts of the guide. Thanks also to Gareth Conlon (Comhlámh), Dorothy Jacob (Self Help Africa) and Aishling McGrath (WorldWise Global Schools) for helpful comments and observations.

Why study visits and immersion programmes?

Here is my hunch. I think the most significant benefit is not in finding answers, but in asking questions, in the un-doing of old patterns, held truths, stale wisdoms…in having a different reference point, a different perspective.’

Varja Lipovsek of East African NGO Twaweza

All of me was learning, not just my mind, as is usually the case. The immersion allowed me to stop analysing people living in poverty as objects of development, but rather just to be with them and allow the learning to emerge.’

Taaka Awori, Liberian

…it still informs some of the decisions that I make’ or ‘it would be a more accurate description to say that the experience has provided me with a lasting sense of perspective, which in turn has had an influence on my decisions’

Participant on the Belvedere School Calcutta Exchange programme, 2010

The Indian NGO The Praxis Institute for Participatory Practices highlighted five key reasons why immersion programmes are important in the broader human development agenda. These are:

- Reality Check – they provide a context and an opportunity to check personal views and frameworks against complex and diverse realities

- Informal Judgment – a chance to better understand development issues from the perspective of other people and communities

- Personal Development – they assist in the development of a more wholistic understanding of diverse realities based on first-hand experience

- Highlights the gap – they offer a platform for internalising the routine ‘disconnect’ between reality and our received understandings of it

- Re-motivates and re-energises – they can promote and help sustain personal and professional motivation around human development agendas.

Chris Minch, author of a 2016 evaluation of Aidlink’s Immersion Programme found that immersions offer first hand experiences of a different way of life and they aim to increase awareness and understanding of the challenges facing those in extreme poverty. The idea behind such programmes is

- To introduce the complexity of inequality and underdevelopment in a context where the power dynamic is more equal than the standard rich-poor or donor-recipient relationship.

- To promote increased levels of knowledge, altered attitudes towards development issues,

- To cultivate a keener sense of global citizenship, and an increased desire to participate in movements towards increased social justice.

(See the discussion in Chris Minch’s evaluation report Aidlink’s Immersion Programme: Review of the Programme and the 2016 Pilot Evaluation Process, October 2016).

Study visits and ‘immersion’ programmes, what do we mean?

In the context of development or development education, study visits or immersion programmes are usually short overseas visits to another country (generally in the Developing World, but not necessarily so), community or location for the purposes of experiencing and studying a range of issues, ways of life and different cultures. Immersion programmes tend to involve staying in a local community, sometimes living in a host family or community (usually for a limited period of time) while experiencing daily life or specific events. On the other hand, study visits are structured learning opportunities often focused on a specific topic or with a particular outcome in mind (engaging in an international action campaign, developing a learning resource around an issue or focusing on a specific issue).

Study visits and immersion programmes (hereafter study visits) need to be distinguished from volunteering projects (or service learning programmes as developed in the US, Australia and elsewhere) which normally involve some form of ‘practical work’ or ‘service’ provision programme. Through combining formal, school or college-based learning with practical ‘in the community’ ‘real-life’ learning, ‘service’ learning promotes experiential learning and civic or community engagement, and sharpens their insights into themselves and their place in the community.

In the Irish context, study visits have been part of the development co-operation agenda since the 1960s (and even earlier in the case of Irish missionary activity). Some of the earliest structured visits included the following:

- Trade union organised visits as part of broader campaigns on Apartheid, Central America and the Philippines

- Church/parish/faith-based group visits focused on similar issues and campaigns or on topics such as liberation theology

- NGO study visits as part of broad constituency building around development issues

- Formal education sector study visits by teachers and students (sometimes in the context of school linking)

- Youth and adult education organisation study visits.

As such, study visits have had a very broad agenda ranging with specific and organised outcomes in mind (usually as part of a broader activist agenda) to more loosely structured ‘general’ learning agendas (usually as part of building a public movement on development and justice issues).

Study visits encompass a broad school; some remain firmly focused on aid agendas and on strengthening the ‘charity’ component of development cooperation while others are strongly political and activist in focus.

The short film Teaching about Nicaragua is based on a Trócaire organised study visit in 2015.

About This Section:

- Introduces study visits and their educational value

- Provides some practical, agenda setting and reflection ideas to help support such visits

- Presents the views and experiences of a range of visit participants

- Includes a number of detailed case studies (there are many more that could be added (we plan to do this from time to time)

- Offers a set of initial links and references for further research and reading.

The educational value of study visits – who benefits?

- They are often ‘life changing’ experiences in that they can regularly take us out of our ‘comfort zone’ and force us to think about our place in the (wider) world

- Often, they challenge us fundamentally; it is a routine response from those who have undertaken study visits that they felt challenged and confronted in many significant ways – not just about ‘over there’ but often about ‘back here’; not just about ‘them’ but, more importantly about ‘us’ and our role in the world

- They encourage us to build links and partnerships with others elsewhere (often overseas), perhaps for the first time and to integrate their thoughts, ideas and suggestions into our work

- They allow us to ‘see for ourselves’ – rather than getting information and reporting ‘second hand’, study visits provide a glimpse into the issues in a more immediate and ‘visceral’ way

- When planned and delivered well (including structured reflection post visit), they can encourage us to think more effectively about how we ‘feel’ about the issues; about how we relate to them personally (and emotionally) and about what our links and responsibilities might be. Ultimately study visits can and should challenge our perspectives

- They are a great source of ideas and resources for ‘teaching and learning’ in formal and non-formal settings – about places, issues and challenges; if planned and delivered well, a study visit will provide ‘rich pickings’ for educational agendas

- If shared effectively across families, peer groups, clubs, communities and schools, they can have a catalytic role in stimulating interest and involvement

- They often offer practical and effective ways to engage in the action agenda in human development at a variety of levels

Was it worth it? Yes, of course – without doubt. I lived in another country for a whole month and some of my preconceived notions were shattered – but for every pre-conceived notion shattered, ten questions raise their heads…’

Jean Sames, religious education teacher, Birmingham, following a study visit in 1977

9 initial questions to think about

Giving time, energy and discussion to some of these questions at the very outset, will deliver immense dividends later, as well as avoiding confusion and even conflict.

The 9 questions below are by no means exhaustive – they are offered to stimulate your initial thinking and planning.

1. Why are you planning a study visit? Are you clear why you are undertaking this project and the demands it places on you, your group and those elsewhere who may be implicated? What outcomes and/or outputs do you expect from the project?

2. Have you integrated the reasons into your planning and agenda for the project (not just the ‘trip’) so that you achieve your objectives?

3. Have you established effective communication and exchange with your partners ‘there’ and have you integrated their ideas and suggestions into your plan (this is often the least developed dimension of many study visits!)

4. Given the cost and energy required to deliver an effective study visit, have you identified the members of the group and have you thought about how they will deliver ‘value’ to the agenda in terms of their positions, capacity, agendas etc.?

5. Have you thought ‘hard’ about the location you are visiting and the possibilities it offers to support your learning objectives (have you outlined these)?

6. Have you considered the basic logistical, administrative and safety issues for not just your group but for others who will be involved in the overall project (the detail can follow later)?

7. In broad strokes, what is the scale and duration of, not just the visit but also the project overall (planning workshops, study visit per se, follow up workshops)?

8. How are you going to ensure your educational outcomes; do you need to involve others to ensure this?

9. Have you contacted others who have organised similar projects in order to share advice, ideas and experiences?

Drawing up a partnership agreement

Have you considered how you might design a ‘partnership agreement’ to underpin the experience and how would you ensure it includes everyone who should be included?

What elements should it include? (for example, roles, context of partnership, educational goals, guiding values and principles, quality, finances, relationships, monitoring and impact, safeguarding, sustainability, reporting, timelines, conflicts of interest resolving conflicts etc.)

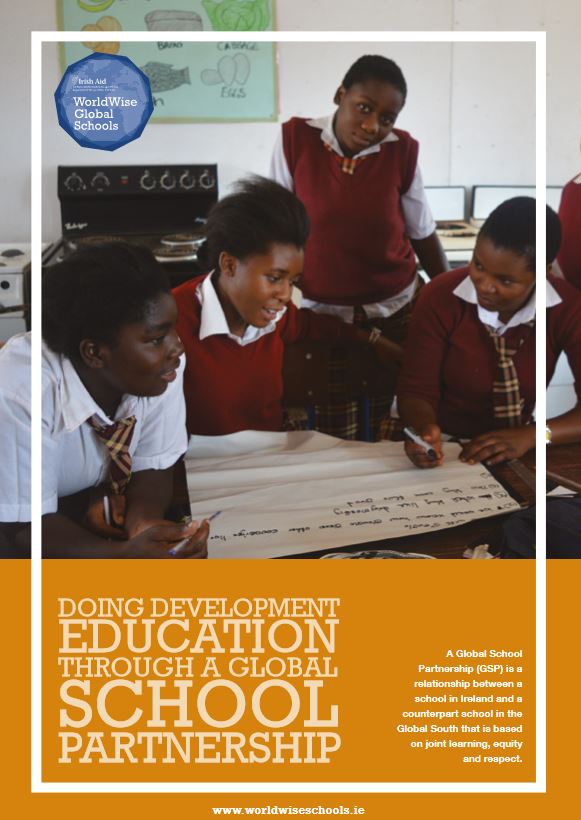

For more suggestions on developing partnership agreements, see Doing Development Education through a Global School Partnership, produced by WorldWise Global Schools.

‘Looking through other eyes’ – observations by Vanessa Andreotti presented at the first Irish Development Education Association (IDEA) conference in 2007 on the theme of Linking and Immersion Schemes.

‘Looking through other eyes’ – observations by Vanessa Andreotti presented at the first Irish Development Education Association (IDEA) conference in 2007 on the theme of Linking and Immersion Schemes.

In approaching any linking and immersion scheme, Vanessa indicated that it is critical that schools and other begin a process of ‘looking through others eyes’. This critically involves:

- Learning to unlearn – learning to perceive that what we consider ‘good and ideal’ is only one perspective. Our perspective is related to where we come from socially, historically, and culturally

- Learning to listen – learning to recognise the effects and limits of our perspective, and to be receptive to new understandings of the world

- Learning to learn from and with people – learning to receive new perspectives, to re-arrange and expand our own perspectives, and to deepen our understanding – thinking beyond our limits

- Learning to reach out – learning to apply this learning to our own contexts and in our relationships with others, continuing to reflect and explore new ways of being, thinking and doing, knowing and relating

Source: Conference report: Linking and Immersion Schemes with the Global South: Developing Good Practice, IDEA 2007

We went there just wanting to help…(but) the insight into culture, people and religion and indeed the ways of education that I gained from this trip was invaluable, it has left me not so much with any answers but with more questions, about the ways of the world, about development and even about myself’.

Ann Marie Reilly, Réalt Volunteer, Coláiste Mhuire, Marino Institute of Education 2008 in DICE Volunteering Charter, DICE Network 2009.

Agenda ideas for pre-visit workshops

Preparing well for a study visit is vital if you are to make the most of the opportunity and achieve your project outcomes and objectives.

Spending an appropriate amount of time in developing a sense of the participating group; addressing expectations and fears; building a common agenda and approach as well as discussing desired results and follow-through will pay handsome dividends and justify the time and expense involved.

Below, we offer some workshop ideas (based on previous study visit experiences) to support such workshops. We have made extensive use of a report prepared by a group of teachers supported by (then) Birmingham DEC (now TIDE ~ Global Learning) in 1979 but have also used materials developed by Aidlink (for its immersion programmes in East Africa), WorldWise Global Schools, Self Help Africa (in its African Development Education projects) and by Concern Worldwide and 80:20 Educating and Acting for a Better World in their DE advocacy work focused on the UN in New York and on Aboriginal Rights in Australia.

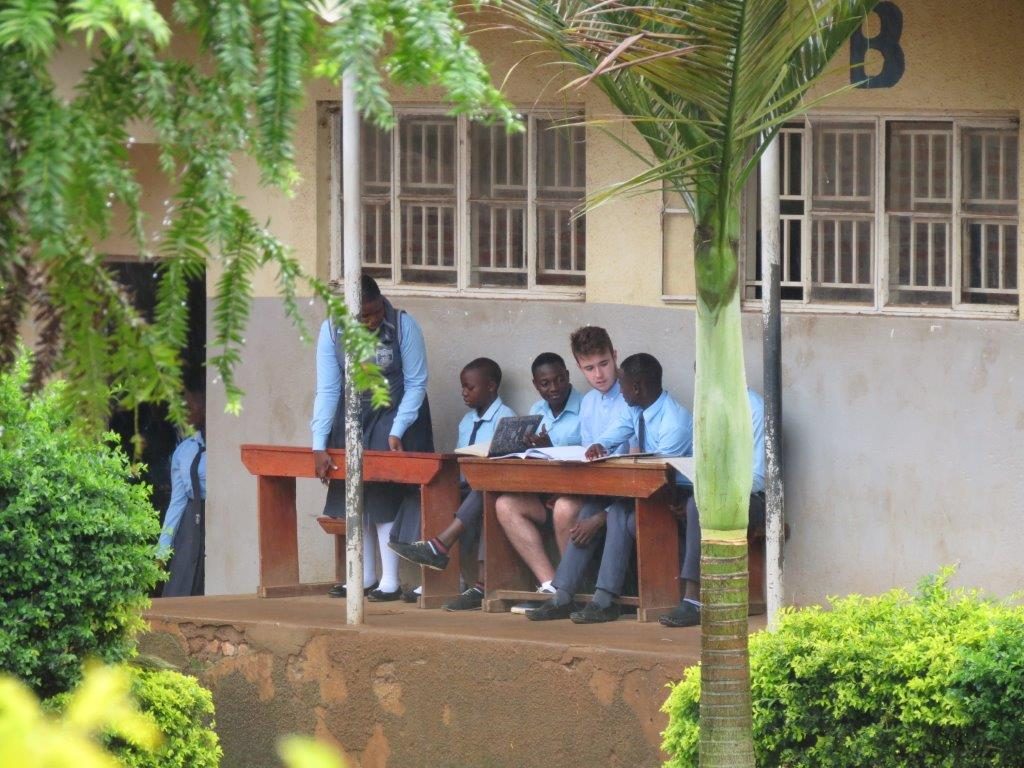

Diarmuid Curtin and Jack O’Connor, winners of the Science for Development Award at the BT Young Scientists 2017, field-tested their seed planter in rural Malawi as part of a study visit organised by Self Help Africa.

Source: SelfHelpAfricaTV, Apr 10, 2018.

For suggestions and ideas in a variety of different contexts see:

- Volunteering – to explore some of the principles and debates involved (in this case in a volunteering context), see: Comhlámh’s Code of Good Practice and the Volunteer Charter

- Schools-based linking – a guide with top tips and ideas for Doing Development Education through a Global School Partnership, produced by WorldWise Global Schools

- In a UK context, for info on school-based global partnerships to explore global issues, see: Connecting Classrooms by the British Council and the wide ranging research report School linking – where next? Partnership models between schools in Europe and Africa by Institute of Education (IoE), University of London

- Youthwork – Insight 7: Developing Global Links, YMCA Ireland reflective practice journal, 2005

- Millennium Development Goals Education Campaign by Michael Doorly and Patsy Toland; see in particular the youth-led advocacy document on the above, see, in particular the project advocacy and lobbying documents produced by the young lobbyists.

A simple but effective model for a study visit is offered by the Birmingham Development Education Centre (DEC) in its report on a 1977 visit to Ghana by a group of teachers.

The report identified 3 main phases (these can also be applied to various components and dimensions of the study visit itself):

- Climate: setting the climate for group learning and introducing the anticipated content and learning.

- Enquiry: exploring and discussing the specific content of the project.

- Synthesis: bringing together the project/visit experiences, discussing and debating their implications and developing future plans from them.

The report then usefully shares some key assumptions and perspectives of this model of learning – these are key to a successful outcome:

- As participants are going to work and travel together, it is important that they know each other especially as regards developing mutual respect and trust and recognising the diversity within the group

- The participants need to identify with and agree the objectives of the visit …and it should be amended appropriately to take their needs and suggestions into account. It is crucial that participants feel a strong sense of ‘ownership’ of the project if they are to stay engaged with the agenda post-visit.

- All participants are a ‘resource’ for the project and their experiences, skills and abilities need to be recognised, shared and ‘harnessed’ for the success of the project.

- The visit must be built on discussion, debate and respect as it is highly likely that disagreements and tensions will emerge and a mediation process will be needed to address this along the way.

- Given that all of us approach an issue (place) with preconceived ideas, pre-judgements and attitudes, participants need to be aware of this and to discuss it appropriately beforehand.

- It is useful to have an overview of the whole project before becoming ‘swamped’ in the detail and the specific agenda.

- Individual and group fears, expectations and plans need to be explored as part of the building process for a visit.

While it is important to have a checklist of educational aims, assumptions and desired outcomes in designing and delivering a study visit project, it is useful also to consider individuals’ needs: these might include:

‘…to feel at ease

… to feel that their viewpoints and experiences are taken seriously by others

… to feel stimulated and challenged by new ideas … to feel that they are achieving something valuable…’ (p.13)

A particularly important question to discuss, especially in the context of visiting a developing country, is the ‘mindset’ we bring. Is it an outlook where we already have both the questions that need to be addressed (as well as the answers to them) in advance or is it one where we travel in a spirit of enquiry with much to learn?

Getting started: a planning workshop

Typically, such a workshop might include a brief set of initial icebreaker activities.

Some initial activities should be designed to support the group in getting to know each other, begin to work together and to begin to discuss the visit etc.

Activities could include:

- Activity 1 – Getting participants to work in pairs to discuss their individual answers to the crunch question ‘why I want to take part in this visit and how I feel about it at the moment?’. Each individual should have the chance to speak without interruption for, say, 5 minutes and then generally discuss each other’s response. Each pair’s responses can then be fed back to the whole group and an initial whole group view can be collated and briefly discussed.

The results of this process can be used later in evaluating the visit.

- Activity 2 – could involve some visual stimulus such as a set of quotes of summary statistics/facts/infographics on the topics/place/people to be visited. Again, participants could work in pairs, responding to the stimulus materials, expressing viewpoints and reactions and later building further on the whole group agenda.

- Activity 3 – could revolve around a set of selected images of the broad study visit location (e.g. East Africa, New York, urban Brazil etc. – use online images, brochures, magazines, textbooks etc.). This time, working in fours, the groups could rank the images, label them etc. (for ideas on using photo-images see here).

Each group could then share its ranking, labelling etc. on a poster with the whole group thus building further on developing a sense of the group and its ideas.

‘I arrived on Friday evening with some apprehensions about the weekend, and the trip as a whole. The weekend programme and indeed the whole venture seemed vague. I had doubts about fitting into the group, and wasn’t sure what my contribution would be either to the trip, or in terms of teaching afterwards. I found the getting to know one another exercises surprisingly easy, and even fun. This got us off to a light-hearted start, although with a serious aim in mind.’

- Activity four – (and more challenging activity) could involve focusing on each individual participant by inviting them to sketch a chart of their life and career to date with particular reference to experiences or desires around the topics or place or people related to the visit (e.g. previous interest in aid and its impact, the situation of women, environment or books read or films seen on, say Africa or the Amazon etc.).

The idea here is to get participants to reflect on how the study visit might relate to or build on previous interests and ideas; it also allows for expanded discussion on the interests and ideas of the group members and should also offer ideas on structuring the visit.

- Activity 5 – a vital activity (which should be given all necessary time and energy as it will help sharpen your thinking and planning for the visit) supports the group in talking directly about the visit and their agendas and expectations.

Working initially in small groups, individuals should consider, record and discuss their responses to the key question ‘What do I hope to get out of this visit/project?’ It might be useful to get each group to record common responses on individual cards (one common response per card) – these can be displayed on a wall for all to see. The cards can then be sorted into categories around common themes and these themes can be further discussed.

The results of this activity should then inform the planning and structure of the study visit and its follow on in order to ensure it begins to address participant’s interests, questions and agendas. If done well, this will add considerable value and impact to the project as well as ensuring participant ownership of the agenda.

Discussing mindsets

In the context of this element it is important to discuss the mindsets we bring to the whole project.

- What is our understanding of the issues to be explored? Do different members of the group have different ideas about the issues? Might ‘our’ ideas be different from those individuals and groups we expect to meet during the visit?

- Do we have as much to learn about the issues and our role with respect to them?

- How do we avoid challenges such as the trap of ‘poverty tourism’ or of being the Western ‘expert’ (and what do these terms mean)?

- What other mind sets might be problematic?

Some typical responses that arise (based on previous visit preparation workshops) include:

“I’m a complete dunce on Africa so need reassurance from an ‘expert’ on even the simplest things. Comforting to find you are not the only one worrying about what to take and whether or not you need a mosquito net!”

“Once we get past our fears and into the work itself, I’m sure we will do a good job; so much talent in the group means that everyone should be in a position to contribute but am still both nervous and excited at the same time.”

“I am hugely excited but very nervous about how Aboriginal Australians will see us. It is different from travelling to an African country where so much of the discussion is about aid. This is different and very challenging.”

“I feel that others in the group are much more experienced and qualified than me but I am determined to make a positive contribution for my own sake as well as that of the group.”

Some debriefing and reflection questions

We do not learn from experiences; we learn from reflecting on our experiences’

John Dewey, 1933

Perhaps one of the weakest dimensions of study visits in recent years has been the process of reflection and evaluation – the trip is over, the excitement is no more, ‘normal’ life has resumed and it is difficult to generate the same level of enthusiasm and energy for such reflection.

And yet, this is one of the most important and significant dimensions of the whole process.

It need not be tortuous, especially if you have set time aside for assessment and review at the end of the visit ‘in country’. Some simple questions, discussion and debate can generate important thoughts and ideas which can be shared with others on the whole process and its outcomes.

The questions suggested below can be answered initially individually but much of the ‘added value learning’ arises from discussing them collectively.

Thinking about initial reflections

- What did I enjoy or not enjoy in the study visit and why?

- What were my feelings during the visit and what do I think about them now?

- In what ways has this experience affected me, influenced my values or beliefs?

- Did I encounter or recognise any cultural similarities and/or differences between my own situation, community, country and (Brazil, Ghana, Northern Ireland etc.)?

- What, if any cultural barriers did I encounter? Describe them

- What did I learn from them and how did I overcome them?

Thinking about connections and relationships

- What connections are there between my own situation/country and where we visited? Did any of these surprise me?

- How do I understand these similarities, differences and connections?

- What did I encounter that I had expected or not expected?

- In what ways has my relationship with the issues/places changed as a result of the visit?

- If I could start over, what could I/we do differently to make this exchange/study tour experience more rewarding? What could I/we have done better?

Thinking about the future

- What outcomes arise from the visit for me, our group, my work, my life etc.?

- What things/behaviours/attitudes might I try to change as a result of the visit?

- In what ways does the visit impact on my career, work etc.?

- What opportunities do I have as a result of the visit/immersion to work against injustice and greater respect for human rights, in my life, my community and more broadly?

Ndey Bakurin, Head of Communications and Education Sector, NEA. Address to teachers at NEA-Tide~ conference, February 2010 (quoted in Global Partnerships for Mutual Learning: teacher development through North-South study visits by Fran Martin in 2011):

This North-South partnership is very unique. It is not a matter of one part giving and the other receiving. It’s a give-give, receive-receive mutual exchange between organisations, individuals and agencies, and in a sense is a model for sustainable development and bridging North-South… All partners contribute equally as nations, organisations, individuals. We have learnt a lot at an educational level, an environmental level, even a cultural diversity level. It is very important and we would nurture it at any cost.’

School Immersion: Vacation or Education?

“One considerable issue is the limited reach of such programmes: relatively few Irish students have, and will, travel, and opportunities are curtailed by means and by school links to the developing world. The traditional classroom-based approach or public awareness campaigns have the advantage of wider exposure. The potential continued involvement after students return home to use their experience to drive change – albeit in the face of leaving certificate and university ‘distractions’ – will in the long term define the success of such programmes. As immersion programmes mature along with the students who travelled on the trips, only time will tell their long-term impact on development.

Past participants are enthusiastic and appreciative, finding their experience “real” and “meaningful”. However, the long term impact of this immersion programme is still emerging.”

School Immersion: Vacation or Education? by Fran Wallace, developmenteducation.ie, August 7, 2012

Key lessons learned...to date

Extract from There and Back Again: Report of a Zambia/Ireland Exchange Project by the National Youth Council of Ireland and 80:20 Educating and Acting for a Better World (2006):

- Preparation is crucial to success – being clear about why the visits are taking place, what each ‘side’ wants to get out of them, consider the size of the group travelling, the length of the visit and what the activities will deliver is crucial. The groups travelling should meet together beforehand – at least a couple of times!

- Build in reciprocity from the outset – having a genuine two way exchange increases the potential for learning and the longer-term impact of the exchange

- Activities to be delivered ‘in country’ need to be prepared in advance – organisations receiving visitors need to be prepared, agendas negotiated and outcomes discussed – activities need to be thought through. A clear, yet flexible agenda is important

- Everyone does not need to follow the same agenda ‘in country’ – breaking into different groups would be helpful and then coming back to share outcomes and experiences within the full group would maximise capacity and results

- Ensure interaction with young people directly – engaging directly, rather than simply via leaders, is important in getting a real feel for the possibilities

- Be realistic about how much can be achieved – having (or creating) expectations that cannot be achieved, especially those around follow through agendas, will damage the agenda and set groups up for failure

- Follow-up is fundamental – everyone who participates is responsible for ensuring that the minimum follow through is achieved – thank you letters, reports, email contact, workshops in your own youth setting, feedback to national structures, etc

- The value of the social agenda – it’s obvious, but it can easily be left to chance

- Sustainability – one of the key results of the exchange programme should be networked groups, we need to think more on the sustainability aspect. Otherwise, we might just be investing in individuals that end up doing little or nothing with their experience

- Monitoring and evaluation – we need to develop monitoring and evaluation tools to effectively measure the results that exchange programmes can yield, we don’t think reports alone are effective enough

- Also – the importance of not being narrow-minded, the effectiveness of exploring group dynamics and individual strengths, amalgamating ideas and experiences is the best way of developing effective practices

Reflection quotes - examples from practice

Quotes from teachers who took part in various study visits, as catalogued by researchers Mella Cusack and Aoife Rush in 2010 in their paper, ‘The authority of a lived experience’: An investigation of study visits as a professional development opportunity for post-primary development educators in the open access journal Policy and Practice: a Development Education Review:

“[I am] more aware of living in a self-sufficient way, something I have learned from Malawians who make everything they need. I have observed since my return how wasteful we are in our society. …I have reduced the amount of ‘stuff’ (mainly unnecessary) that I buy. If I don’t need it, I don’t buy it.”

“Being influenced by the strong sense of community, I have felt the urge to give something back to my own community. So from next week I will be volunteering at the homework club in the Immigrant Centre in [X] every Thursday.”

“When Trócaire told me that the [DE Programme] this year was focusing on climate change, I was disappointed as I really wasn’t very knowledgeable about this topic. I had heard about it many times on the news but didn’t pay much attention…now it’s not just a concept but a real issue for millions of people…”

“…the greatest challenge here was to communicate my experience in a way which reached my students. In the end it turned out to be far easier than I expected as the pictures, video and telling the story of our visit spoke for themselves.”

“…I can now teach from first-hand experience and my word carries the authority of a lived experience. This has proved to be invaluable. It is not just somewhere out there, but the country that [X] was in and brought us back photographs and stories.”

Jonny Byrne, John Topping and Duncan Morrow wrote in their 2015 evaluation, Future Generations Evaluation: Lessons from the six international study visits, Ulster University (page 15):

‘Visits abroad are ‘junkets’ when the trip is the purpose rather than the vehicle. In this case, the trip was the vehicle for building relationships and it is not clear that the burden of historic prejudice can be changed unless new relationships are given a new context in which to grow.

Future Generations suggests that study visits, if properly mentored, organised and monitored can play a critical role in changing relationships at home and are not confined to learning about situations abroad.’

Suggested sources (to get started!)

These suggested sources are in addition to the resources listed throughout the unit, including the videos, study visit reports and evaluations.

Doing Development Education through a Global School Partnership by WorldWise Global Schools, 2015.

- Linking between Ireland and the South: Good Practice Guidelines for North/South Linking by Cathal O’Keefe, Irish Aid, Dublin, 2006.

- Report of Conference on Linking and Immersion Schemes with the Global South – Developing Good Practice by the Irish Development Education Association, 2007.

- Aidlink’s Immersion Programme: Review of the Programme and the 2016 Pilot Evaluation Process, by Chris Minch, Aidlink, October 2016.

- There and Back Again: Report of a Zambia/Ireland Exchange Project by National Youth Council of Ireland and 80:20 Educating and Acting for a Better World, 2006.

- ‘The authority of a lived experience’: An investigation of study visits as a professional development opportunity for post-primary development educators, by Mella Cusack and Aoife Rush, Policy and Practice Issue 10, 2010.