What The Fact?

Fact-checking Trump’s attacks on the World Health Organization

Trump’s Bout With COVID-19 Might Be Hurting His Reelection Chances. Graphic by Peter Stephens (adapted via Flickr under CC-BY 2.0 licence)

- Colm Regan

The Claim

Following his temporary ending of funding to the WHO, President Donald Trump sent a letter on May 18th 2020 to Dr Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, Director General of the World Health Organisation, in which he made a number of claims and used these to justify his administration’s decision to begin the withdrawal of funding.

In his letter sent to the WHO on May 18th 2020, Trump claimed:

- the WHO had argued that the new virus ‘was not communicable’ even though there was credible information that the virus could be transmitted human-to-human

- the WHO accepted China’s assurances about the coronavirus at face value and had praised China for its transparency

- the WHO had fought the US in its decision to impose travel restrictions on China and that that if it had not put such restrictions in place ‘probably hundreds of thousands more’ would have died.

Overall, Trump claimed that while largely funded by the US, the WHO was significantly ‘China centric’.

The Verdict

The claim is rated false (inaccurate based on the best evidence publicly available at this time), on a number of levels:

- The claims regarding the World Health Organization made by Donald Trump (and repeated by many others) are based on a highly selective set of bits of information and on selected timings.

- Donald Trump’s arguments about specific WHO statements and timings were translated into generalised claims about WHO failures and political leanings and into comments about the WHO agenda in general.

The Evidence

Trump made his major announcement on funding for the WHO at a White House coronavirus task force daily briefing on April 14, and accused the WHO of ‘severely mismanaging and covering up the spread of the coronavirus’.

While there is evidence that China was slow to report the virus outbreak, there is no evidence that the WHO covered up the spread of the coronavirus. The South China Morning Post reported that the first coronavirus case in China could be traced back to Nov. 17th but China did not report it to WHO as a novel disease to until Dec. 31.

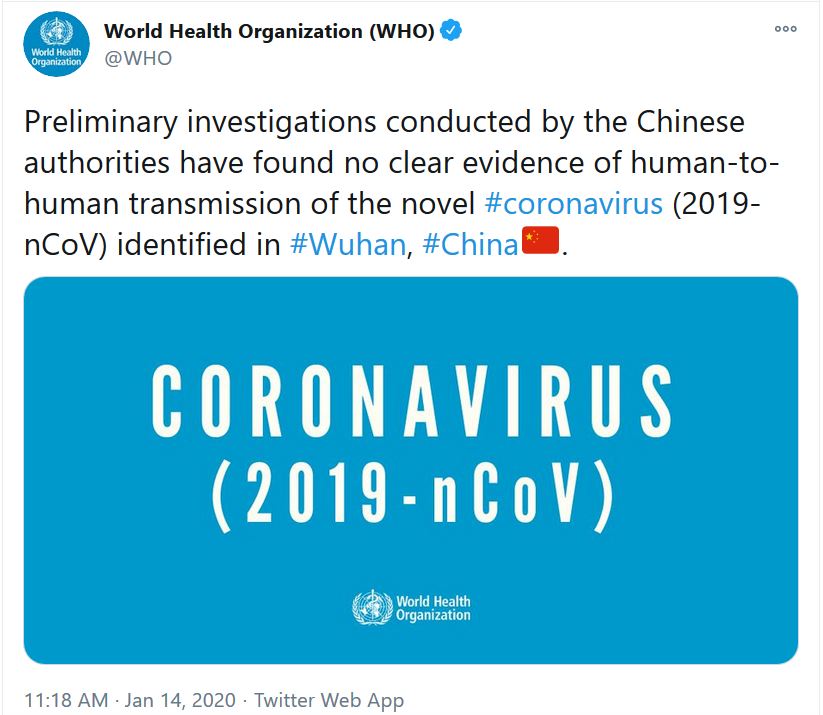

The President also claimed there was ‘credible information’ to suspect human-to-human transmission in December 2019, yet WHO wasn’t notified of an outbreak in Wuhan in China until Dec. 31st. In mid-January, the WHO had shared ‘preliminary’ information from China that ‘found no clear evidence’ of human-to-human transfer, but it continued to consider such transmission possible.

Trump’s claim is most likely based on an early morning Jan. 14 tweet from the WHO.

However, lack of evidence, especially in preliminary results, does not imply the WHO was saying the novel coronavirus could not be spread between people.

On that same day WHO cautioned that there might be some human-to-human transmission of the virus among family members in China.

‘From the information that we have it is possible that there is limited human-to-human transmission, potentially among families…But it is very clear right now that we have no sustained human-to-human transmission’

– Maria Van Kerkhove, the acting head of WHO’s emerging diseases unit in a Jan. 14 news briefing.

Trump argued that the WHO ‘took China’s assurances’ about the coronavirus ‘at face value … even praising China for its so-called transparency’. But earlier in the process Trump had thanked China for ‘their efforts and transparency’ and said he trusted that China would provide his government with all of the necessary information.

During a Jan. 22 interview, CNBC’s Joe Kernen asked Trump if he trusted the information coming from China and Trump said he did (and further reported by CNBC).

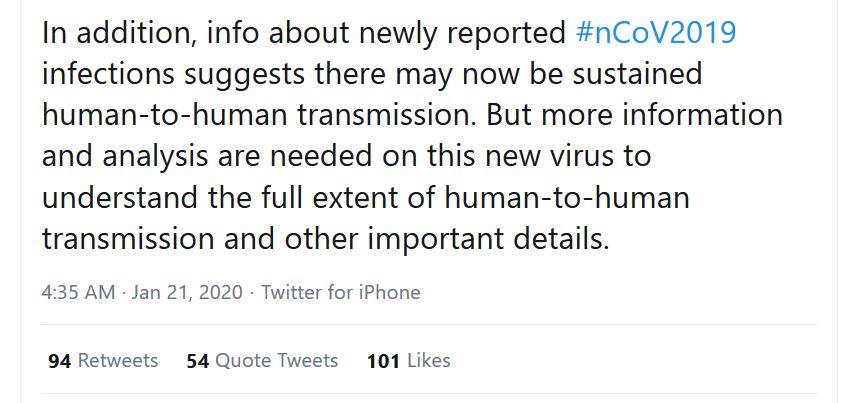

By January 20th, the WHO’s Western Pacific Region stated ‘It is now very clear from the latest information that there is at least some human-to-human transmission of #nCoV2019′ and in a tweet explained ‘Infections among health care workers strengthen the evidence for this’. A follow-up tweet also indicated the possibility of viral transmission that continues, rather than dying out in a small group of people.

Trump exaggerated when he insisted the WHO ‘actually fought’ the U.S. over his decision to impose travel restrictions on China. WHO leaders have never publicly criticised the U.S. for that decision, although they did advise countries not to enact travel restrictions in reaction to the spread of the coronavirus.

Research to date referred to by the WHO has shown that while travel restrictions can delay the exportation of viruses, they cannot contain the spread. Despite this, Trump repeated the claim without any evidence, that if he hadn’t put restrictions on travel from China ‘probably hundreds of thousands more’ would have died.

The US President’s announcement was criticised by health experts and organisations, including the American Medical Association, which called it a ‘dangerous step’ and ‘short sighted’ at a time when the pandemic worldwide has cost so many lives. (a view shared by the medical journal The Lancet via their 1-page statement following the publication of Trump’s letter).

With regards to the ‘China-centric’ point about the WHO, it is important to frame this comment within a wider pattern of commentary that has been shared by President Trump during his presidency and even prior to 2017. Washington analysts recently concluded that the White House sees China as a ‘strategic threat‘, as reported by ABC News. Illustrations of this include:

- US presidential candidate Trump stated that the concept of climate change “was created by and for the Chinese in order to make U.S. manufacturing non-competitive” in 2015.

- President Trumps’ continuous referencing of the virus as the ‘China virus’, despite calls from global health officials to avoid labels associating the disease with a particular nation or ethnic group, which raise concerns about stigmatizing Asian-Americans and Asians in general in 2020.

A note on WHO

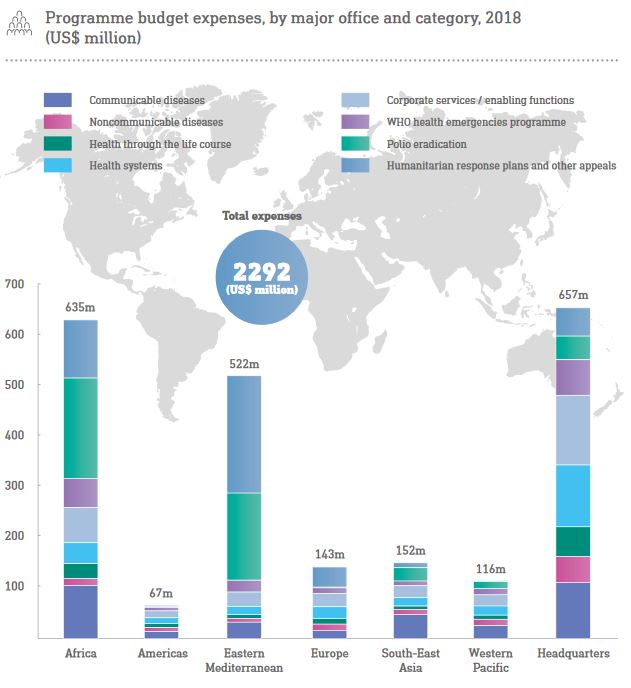

Based in Geneva, the World Health Organization was established in 1948 as part of the United Nations; it has a broad role in coordinating international health policy. Despite this mandate, the powers of WHO are significantly limited. The organisation is managed by the World Health Assembly, made up of representatives of the WHO’s 194 member nations. Its current director-general is Dr. Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, a former minister of foreign affairs and minister of health in Ethiopia; he was elected for a five-year term in 2017. The WHO has no direct authority over its 194 member states.

The WHO has achieved much over the years, for example its role in eradicating smallpox (1979) and also polio in Africa (2020) and its various vaccinations programmes which have transformed the lives of millions of children. However, the organisation was heavily criticised for its slow response to the 2014 Ebola outbreak.

The organisation describes its key functions to be (among other things)

‘shaping the research agenda…providing leadership on critical health issues …setting norms and standards…and monitoring and assessing health trends’.

One of its key roles stems from its exclusive authority to declare a public health emergency of international concern, a power it was given in 2007. Since then it has declared such an emergency six times, most recently during the current novel coronavirus pandemic. During such emergencies the WHO can issue guidelines on how countries should respond, including with travel and trade restrictions. But the guidelines are nonbinding and the organisation has no enforcement powers.

WHO staff have to work practically in order to conduct monitoring visits – they cannot compel a country to let them visit or enter. It is a diplomatic tightrope each and every time, so for practical reasons they have to negotiate and secure access on the ground to understand and assess viruses as they are emerge.

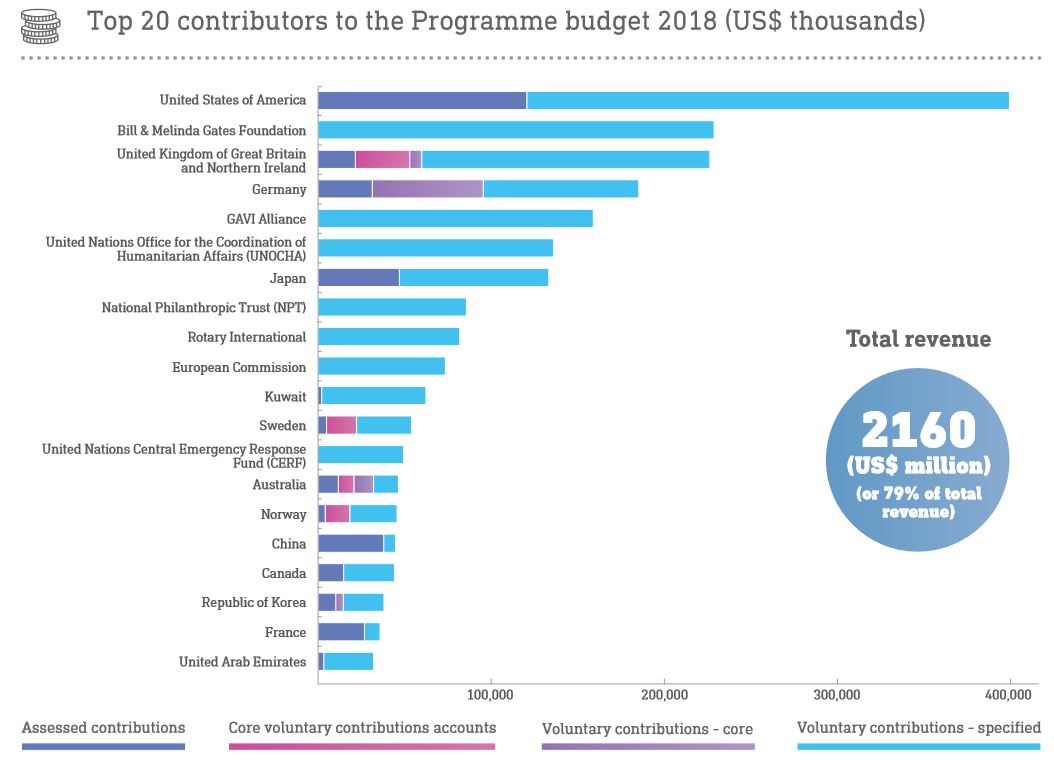

Approximately 20 percent of the WHO budget comes from mandatory dues paid by members; the rest is made up of voluntary donations from governments and private partners.

Unlike dues, voluntary contributions are often earmarked for specific initiatives, which can complicate the WHO’s ability to set its own course. The top voluntary contributors by volume include the United States, the United Kingdom, and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. But the funding situation looks very different when translated into per capita terms (as is the norm in international development measurement metrics). The Nordic countries of Norway, Sweden and Denmark top the table.

Over the years, the WHO has become increasingly dependent on voluntary contributions and this puts pressure on the ability of the organisation to set its own agenda and to align its goals with those of its donors. For instance, the Trump administration in the US reportedly threatened to cut U.S. contributions in 2018 if other member states proceeded with a resolution to encourage breastfeeding.

For more on this issue of funding and funders see the 2018 report by the US Brookings Institute, Who Funds the UN and other multilateral institutions? by John McArthur and Krista Rasmussen.

Conclusion

- The claims regarding the World Health Organization made by Donald Trump (and repeated by many others) are based on a highly selective set of bits of information and on selected timings.

- Donald Trump’s arguments about specific WHO statements and timings were translated into generalised claims about WHO failures and political leanings and into comments about the WHO agenda in general.

Verdict

Based on the What The Fact? scales guide, the claim is rated as False – the claim is inaccurate based on the best evidence publicly available at this time.

developmenteducation.ie’s What The Fact? supports the code of principles of the International Fact Checking Network. We check claims by influencers, from local to national to transnational that relate to human rights and international human development.

Transparent fact checking is a powerful instrument of accountability, and we need your help.

Send tips and ideas to facts@developmenteducation.ie

Join the conversation #whatDEfact on Twitter @DevEdIreland and Facebook @DevEdIreland

- Tagged as: China, Covid-19, Donald Trump, global health, health, virus, World Health Organisation

Deniers, Delayers and Regulators, Oh My! Who’s involved in greenwashing?

Who is responsible and who is to blame for practices that can only amount to being called greenwashing? A teachers’ guide by Rachel Elizabeth Kendrick

A teachers’ guide to Greenwashing

A guidebook to support teachers and students in learning about greenwashing as a barrier to sustainable development.

Youth Rising: India’s Vote, India’s Future

Trishla Haryani looks at the 2024 Indian election and the critical role of young people’s vote in shaping it’s political landscape.

Under the Gavel: Are International Courts and Bodies Working?

Daniel McWilliams looks at how the ICC and the ICJ function and any challenges and criticisms faced by them and other international bodies.

30 smeach chárta ar líne: Bia, cothú agus an domhan

‘Foods’ stands for diversity, nutrition, affordability, and safety. A greater diversity of nutritious foods should be available in our fields, in our markets, and on our tables, for the benefit of all.

Extra-curricular Opportunities at Post-Primary Level

Fancy organising a workshop? Many NGOs have members of staff who do outreach and education visits to schools as part of their education programmes.