ICC. Photo by Anemoontjes via Flickr (CC BY-ND 2.0)

This feature has been developed as a guide for Politics and Society and CSPE teachers and students to explore the International court system.

This teaching unit is recommended for teachers of the following post-primary subjects:

- Politics and Society (LC): Strand Three – Rights and Responsibilities

- CSPE (JC): Learning Outcomes 1.5, 1.7, 1.9 and 1.10

In May 2024, the International Criminal Court (ICC) issued an arrest warrant for Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu for alleged war crimes in Gaza. Shortly after the announcement, the Israeli government and media, along with prominent figures such as U.S. Senator Lindsey Graham (Rep.) and the German government, quickly condemned the ICC and denied the allegations, despite Netanyahu facing charges for war crimes and crimes against humanity. The most serious among these charges is the charge of genocide. In light of this case, an important question arises:

Are international courts and bodies working?

To explore this question, we must first examine the purpose and powers of the United Nations (UN) and the ICC. It is also necessary to consider what reforms or improvements could help these institutions work more effectively. Finally, it is also important to understand Ireland’s role within these international bodies.

The United Nations

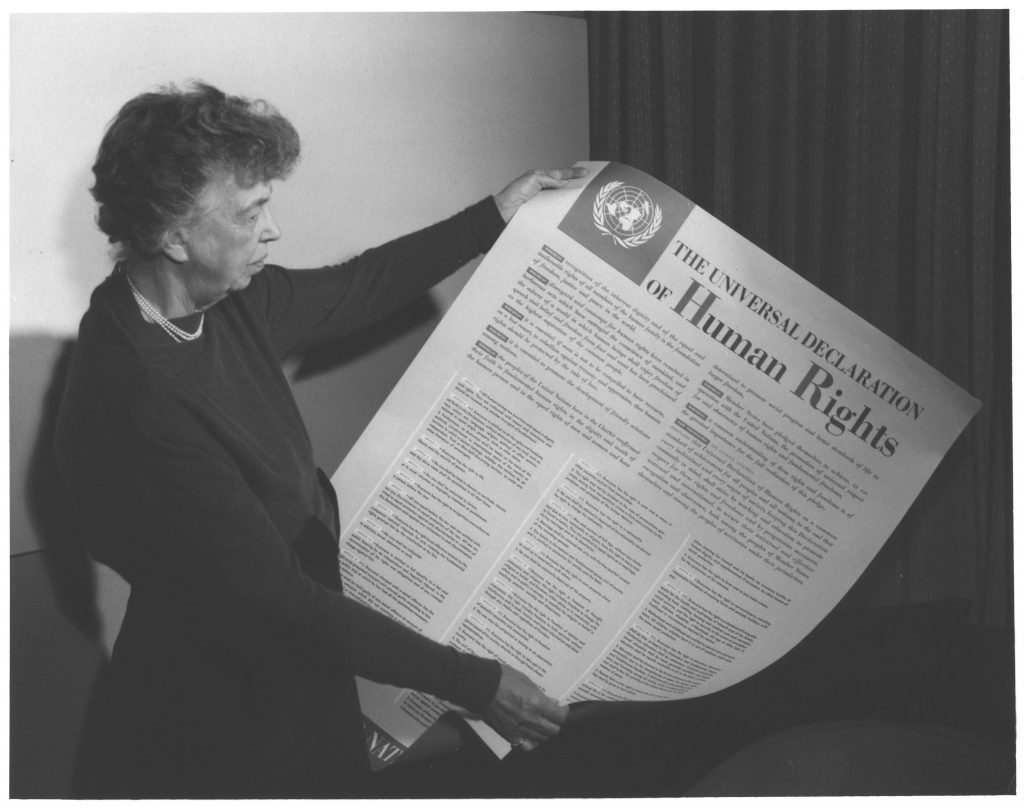

Eleanor Roosevelt holding up the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in 1948. Photo: UN

“WE THE PEOPLES OF THE UNITED NATIONS [ARE] DETERMINED to save succeeding generations from the scourge of war… and to reaffirm faith in fundamental human rights, in the dignity and worth of the human person, in the equal rights of men and women and of nations large and small, and to establish conditions under which justice and respect for the obligations arising from treaties and other sources of international law can be maintained, and to promote social progress and better standards of life…

The United Nations (UN) was created in the aftermath of World War II to prevent such horrors from happening again. It emerged in response to the systematic mass murder of millions of European Jews and other political and social enemies of the Nazi regime. To achieve this goal, the UN provides a forum for international cooperation and a platform to resolve global disputes without resorting to military action.

One of the UN’s core institutions is the International Court of Justice (ICJ). Established under the UN Charter in 1945, the ICJ serves as the organisation’s highest legal authority. In contrast, the International Criminal Court (ICC) is a more recent body. Founded in 1998 by the Rome Statute, the ICC operates independently of the UN, though it often collaborates with it.

While the ICJ and ICC share some common goals, they serve different purposes. This article focuses specifically on the role and effectiveness of the ICC.

[For more information on the ICJ vs. the ICC see the Explainer below.]

United Nations, United Nations General Assembly. Photo by Paul VanDerWerf via Flickr (CC BY 2.0)

The International Criminal Court

“The… [ICC] investigates and… tries individuals charged with the gravest crimes of concern to the international community: genocide, war crimes, crimes against humanity and the crime of aggression.”

Most people would agree that these are good aims. After all, who doesn’t think, publicly at least, that “the gravest crimes” should go unpunished on the international stage?

It is important to understand that most international state and non-state actors—states, groups and individuals—whether prime ministers, politicians, combatants or private citizens, do not question the fact that crimes against humanity are wrong and that those who enable or commit them should be punished.

However, questions of legitimacy for these bodies may arise when applying the definition of a “war crime” in different international contexts. For example, it is sometimes claimed that one person’s war crime is another person’s act of self-defence.

The ICJ v the ICC

ICJ | ICC | |

Founded | 1945 (UN Charter) | 1998 (Rome Statute) |

Location | The Hague, Netherlands | The Hague, Netherlands |

Responsibilities | Settle legal disputes between states in accordance with international law Provide advisory opinions on legal questions referred to it by authorized UN bodies and specialized agencies | Prosecute individuals responsible for serious crimes of international concern e.g. genocide, war crimes, crimes against humanity, and the crime of aggression. |

Jurisdiction | Countries that accept its jurisdiction or are UN members. | Individuals whose countries are parties to the Rome Statute or who commit crimes in those states. |

Remit | Inter-state disputes (e.g., border disputes, treaty violations). | Criminal cases against individuals. |

Relation to UN | Main judicial body of the UN. | Independent from the UN, though it may collaborate. |

Judges | 15 judges elected by the UN General Assembly and Security Council. | 18 judges elected by the Assembly of States Parties to the Rome Statute. |

Enforcement | Relies on member states or the UN Security Council to enforce its decisions. | Relies on member states to execute arrest warrants, for example. |

Example case | Nicaragua v. United States (1986): The ICJ ruled that the U.S. violated international law by supporting Contra rebels in Nicaragua against the democratically elected government. | Prosecutor v. Thomas Lubanga Dyilo (2012): The ICC convicted Lubanga, a Congolese warlord, for conscripting child soldiers. |

Three main Challenges

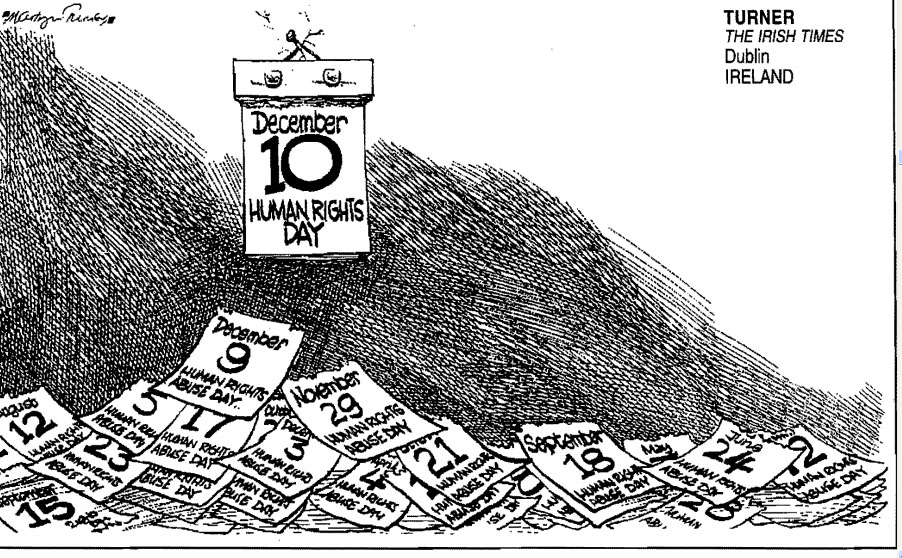

The UN and the ICC, along with other related international courts and bodies, face three major challenges in fulfilling their roles. These roles include supporting human rights, promoting international justice, and facilitating diplomacy. The three main challenges are:

questions of legitimacy

political interference

resource constraints

1. The Challenge of Legitimacy

Despite the terrible body count of its offensive (45,000+ killed, 70% of whom are women and children) Israel maintains that it is only defending itself against Hamas after the October 7th attacks by seeking the total destruction of Hamas in the Gaza Strip. Israeli leadership was quick to respond to the ICC’s arrest warrant for Netanyahu by alleging that the ICC is antisemitic and biased against Israel (Israel is not a member of the ICC) and therefore illegitimate.

These accusations were then repeated by powerful actors in the global community allied to Israel. In this example, by questioning the neutrality of the Court, Israel, supported by the US and others, hampers its work and calls into question its legitimacy to rule. This sets a dangerous precedent in the exercise of international justice by the ICC. That is that, states can pick and choose which judgements of the Court to follow according to their respective government and politics. The ICC simply cannot function in such an environment where international law doesn’t apply equally to everyone everywhere.

2. The Challenge of Political Interference

As well as the well-documented political interference from Israel against the UN and ICC happening currently, another example is the frequent political interference in the form of accusations of geographical and racial bias that the ICC has faced from many African governments. The African Union has criticised the ICC in recent years for focussing too much on the alleged crimes of African leaders while ignoring alleged cases in other parts of the world. This is illustrated by the fact that more than half of the cases opened by the ICC focus on the African continent.

The legitimacy of the UN is also often called into question by political interference which can take the form of tit-for-tat voting on UN Resolutions, especially on the UN Security Council. Often, groups of allied countries will vote for Resolutions which complement their government and politics and vote against Resolutions which do not. This political interference is clearly against the spirit of cooperation expressed in the Charter.

The reality of the related challenges of questions of legitimacy and political interference in the work of the UN and the ICC for Ireland as a member of these institutions was demonstrated recently by the Israeli Foreign Minister making more baseless accusations of antisemitism against Taoiseach Simon Harris and Ireland as a whole. Israel is displeased with Ireland’s consistency in calling out alleged Israeli war crimes in contrast to the silence of many Western nations. Therefore, in what Uachtarán na hÉireann, the President of Ireland, Michael D. Higgins called “gross slander and defamation” the Israeli government seeks to delegitmise Ireland and the ICC by way of political interference. This exchange followed Israel’s closing of its embassy in Dublin in December 2024 for the reasons outlined above.

3. The Challenge of Resource Constraints

Like many international courts and bodies, the ICC and the UN is funded mainly through contributions from member states. This means that arguments sometimes happen between member states about who is paying above the odds, who should pull their weight more in terms of funding and whether or not countries are getting value for money (as they see it) for the funding they provide.

This makes the ICC and the UN even more vulnerable to the related challenges of questions of legitimacy and political interference as detailed above and this challenge was highlighted by the UN itself in February 2024 when it declared that “A cash crunch… threaten[s] to hinder… human rights investigations”. Recent direct appeals for cash from the ICC also illustrate the reality of this challenge.

Permanent Premises of the International Criminal Court. Photo by Rick Bajornas/UN Photo via Flickr (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

It is important to consider some examples of when the UN and the ICC works as intended to help inform our understanding of these institutions. Firstly, the UN’s success in eradicating smallpox in 1980 is rightfully held up as a good example of the UN working as intended. This marked the first time in human history that a disease had been successfully eradicated by humans thanks to international cooperation. Also, despite some recent criticisms of the UN’s peacekeeping missions in the Central African Republic, for example, the UN peacekeeping mission in Namibia which finished in 1990, is lauded as “the first major success” for the UN working effectively to support human rights and enable democracy through deploying peacekeepers.

Similarly, another success of the ICC which should be a template for present and future actions is the successful prosecution of Congolese warlord Bosco Ntaganda for war crimes, in 2019.

Where does Ireland feature?

Ireland has been an active member of the modern international community for decades. It joined the UN in 1955 and has consistently contributed to achieving the aims of the Charter through its advocacy for human rights, UN Security Council membership and through its contribution to UN peacekeeping forces, most notably in Congo and Lebanon.

The Irish peacekeeping detachment in Katanga, Congo are depicted in the film The Siege of Jadotville and Ireland’s dedication to the UN peacekeeping mission in Lebanon (UNIFIL) has been in the news recently given Israel’s invasion of southern Lebanon where Irish peacekeepers are stationed.

The country is also a strong supporter of the ICC and was among the first countries to sign the Rome Statute in 1998. Ireland has consistently contributed to the aims of the ICC since its foundation by vocally supporting international justice and providing generous financial contributions to the Court. Ireland has never had a case brought against it in the ICJ or ICC and this reflects Ireland’s status as an essential advocate and a trusted partner in working for international diplomacy and human rights.

In addition, several respected Irish experts represent the country within the UN as Special Rapporteurs (SRs). One of them is Prof. Siobhán Mullally, appointed in 2020. She currently serves as the UN Special Rapporteur on Trafficking in Persons, especially Women and Children.

UNIFIL 33 Flag Party. Photo by Óglaigh na hÉireann via Flicker (CC BY 2.0)

In her role, she addresses issues related to human trafficking, advocating for the rights and protection of vulnerable populations.

At the time of writing, Ireland is currently represented at the ICJ by Blinne Ní Ghrálaigh KC who has spoken in Court in support of cases against Israel.

What do we want from International Courts and Bodies?

“The UN should be the spearhead on creating a new, sustainable, green, inclusive, and fair world.”

Here, Pablo Galindo, the UN General Secretary’s Envoy on Youth, is expressing what he thinks the UN should be. Therefore, we can suppose that currently the UN and other bodies aren’t living up to their intended purpose. The definition of spearhead is “an individual or group chosen to lead an attack movement.”

So, what Mr. Galindo and many others in the global community want, is for the UN to be proactive in upholding human rights, delivering sustainable development and prosperity, and facilitating diplomacy. In other words, rather than waiting for crises to come to a head the UN should act first to prevent them. Being proactive may help avoid the worst effects of the three challenges mentioned above facing international Courts and bodies such as the UN.

However, this aspiration is not a blueprint and it is for international leaders and citizens to decide how they want to be served by these international Courts and bodies. There is not one easy answer to the many more questions this raises: What might a more proactive UN look like? How might the UN and related bodies such as the ICJ and ICC reform their processes in order to be more proactive and less reactive? Do we want to see these bodies clean up after the fact or do we want to see more direct intervention through war crimes tribunals, peace and reconciliation work and conflict resolution for example?

What is clear however is that international courts and bodies are most effective when their member states cooperate. The ICC or the UN as organisations can’t fix these problems. Their member states must be able and willing to make changes. The three interlinked problems of legitimacy, political interference and resource constraints can only be addressed by the member states of international Courts and bodies acting in good faith within these institutions to help them work properly.

In politically charged times such as these, given the suffering from the Russian war in Ukraine and the Israeli war in Gaza, for example, it is important that cooperation prevails so that the international Courts and bodies can work more effectively to achieve their aims for the good of humanity. One concrete method through which this enhanced cooperation may be achieved is if the media and informed private citizens are more vocal in calling out hypocrisy and bad faith actors in these institutions when they see it. Now that the internet and social media is so widespread, alternative narratives have the potential to be seen by a wide audience and make a true difference by putting pressure on the most hypocritical and cynical states to change their ways for the good of humanity.

To Conclude

The ICC and the UN were established to prosecute future war criminals and ensure nations settle differences diplomatically rather than militarily. Due to challenges such as questions over their legitimacy, political interference and resource constraints however, the ICC and the UN are sometimes seen as not working properly.

It is incredibly important that we remember the word universality. It binds the related challenges of legitimacy, political interference and resource constraints.

A crucial element of the UN, ICC and all international courts and bodies is that they are either for all of us, or they are for none of us. We all must be held to the same standard when it comes to upholding human rights as we are all human and equally deserving of the universal human rights enshrined in the UN Charter.

Finally, international courts and bodies comprise so much more than what we’ve seen above. Here we focused only on the UN and the ICC. We were also introduced to the UN Security Council, UNSC Resolutions, the ICJ and Special Rapporteurs. Understanding these and other related bodies such as UN agencies and human rights committees for example, is vital to fully understanding international courts and bodies and if they’re working.

Daniel McWilliams is a linguist and educator living in Vietnam, having taught Irish, English and Spanish in Ireland, England, Canada, Spain and Vietnam.