What The Fact?

Were Irish people the ‘first slaves in America’?

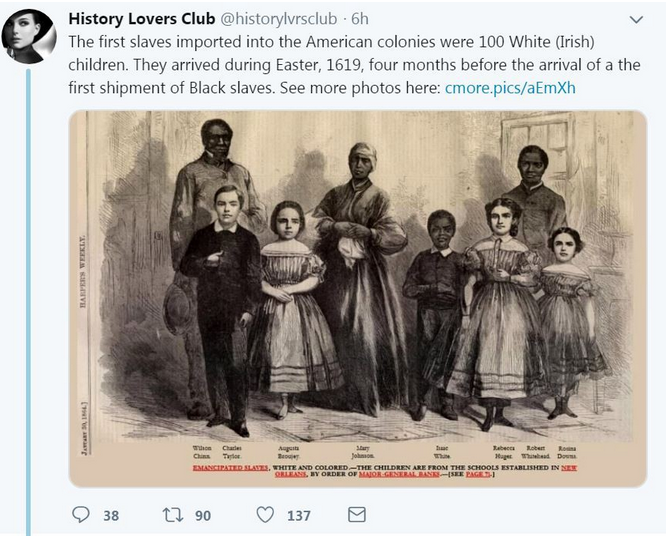

Emancipated slaves brought from Louisiana by Colonel George H. Banks in December 1863. Photo by Myron H. Kimball – adapted (via The Met Museum, CC0 1.0 license)

- Liam Hogan

- November 6, 2020

The Claim

On the 27 August 2019 the Democratic Party Presidential Candidate Kamala Harris marked the 400th anniversary of the first recorded importation of enslaved Africans to Virginia by calling for a reckoning with her country’s “history of slavery and institutional racism.”

Two days later the frequent Fox News contributor and right wing author Janie Johnson (who has circa 210,000 followers on Twitter) tweeted a rhetorical response to Harris stating “What about the Irish the FIRST slaves of America?” the implication being that Irish people were enslaved in Colonial America before African people.

The Verdict

The claim is rated false (inaccurate based on the best evidence publicly available at this time), on a number of levels:

- Irish people were not enslaved in Colonial America, nor were they the first people indentured in Early Virginia.

- The claim that they were the “first slaves of America” is rated as false on both counts.

- It is evident that this false claim appropriates and distorts the history of the transportation in 1619 of one hundred poor English children who were sent from London to Virginia where they were to be bound out as apprentices.

The Evidence

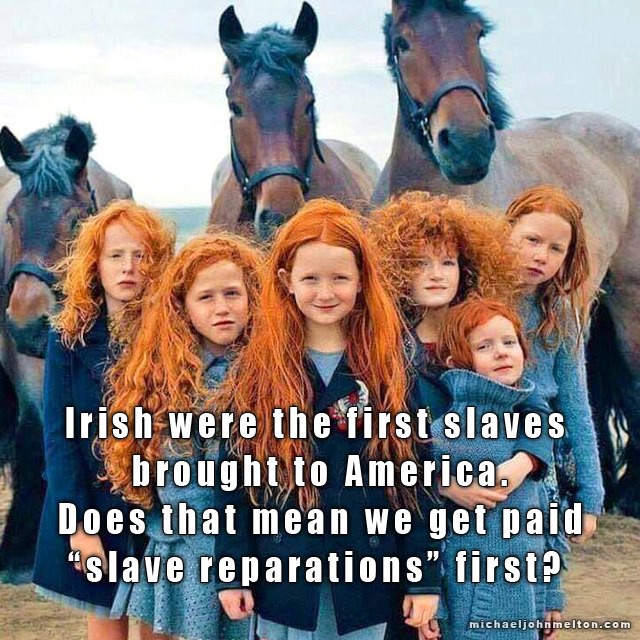

In early August 2019 another “Irish were the first slaves” meme was created by Michael John Melton, a self-published author and ‘lizard people’ conspiracy theorist, and published on his Facebook page. As his followers shared it, the meme quickly began to circulate across thousands of users’ timelines.

The misuse of the photo did not bode well for the historical veracity of its assertion. The image the conspiracy theorist used did not show ‘Irish slaves’ nor Irish children. It was taken on a beach in Holland by Igor Borisov for Vogue Bambini magazine in 2015 and all of the children in the picture are Dutch.

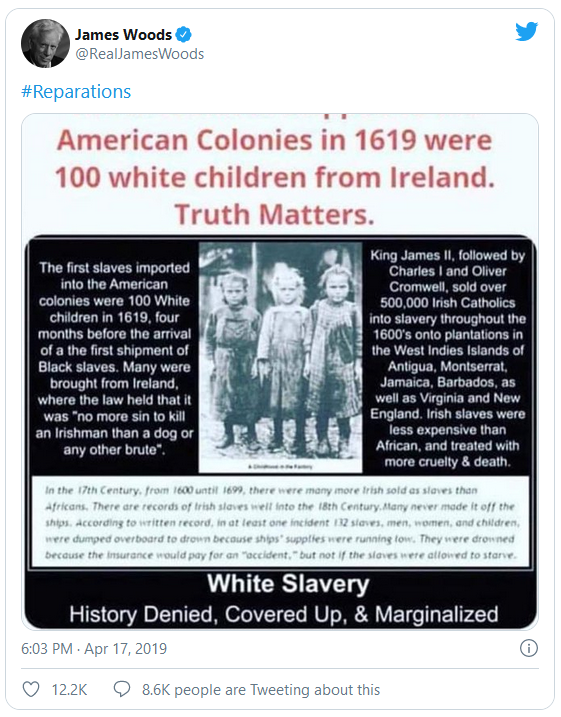

This was preceded by a similar use of another “Irish were the first slaves” meme by the actor and far-right political activist James Woods on 17 April 2019. He shared the meme with his 2.1 million followers to help proliferate belief in the claim that Irish people were the “first slaves shipped to the American colonies” so as to deny or mock reparations for slavery.

And in 2018 the popular History Lovers Club twitter account published a variation of this to its then 400,000+ followers, claiming that “the first slaves imported into the American colonies were 100 White (Irish) children.”

Again this questionable “fact” was appended by an unrelated image, a Harper’s Weekly woodcut based on a photograph taken by Myron Kimball of emancipated slaves from Louisiana (December 1863). The original can be found at the Met Museum.

So it’s clear that three basic questions need to be answered. (1) is this claim true? (2) And if it is not, then what history is it distorting? (3) What is the political purpose of such propaganda?

The English Poor Law in 1619

In 1619 one hundred poor English children (not Irish) between 8 and 16 years of age were sent to Virginia from London. This transatlantic transportation was in essence a radical extension of the English Poor Law (1601) where the children of English paupers were to be provided for by being bound out as apprentices:

“for the setting to work of the children whose parents shall not, by the said Churchwardens, and Overseers, or the greater part of them, be thought able to keep and maintain their children.”

Those that survived that journey were to be bound out as apprentices for seven years.

In November 1619 the Virginia Company requested that another hundred children be sent from London but this time the minimum age was set to 12 years. They were to be bound to their masters in the colony until they reached the age of majority (21 years old), or if girls, until 21 or married. Upon finishing their service they were promised corn, some cattle, housing and twenty five acres of land “to hold in fee simple…to every of them, and their heirs.”

But on this occasion, many of the children refused to go as on 28 January 1620 Sir Edwin Sandys, the London-based treasurer of the Virginia Company, complained to Sir Robert Naunton that “now it falleth out that among those children, sundry being ill disposed, and fitter for any remote place than for this city, declare their unwillingness to go to Virginia, of whom the City is especially desirous to be disburdened and in Virginia under severe masters they may be brought to goodness.” He thus requested “higher authorithie” to “transport theis persons” to Virginia “against their wills.”

On 31 Jan 1620 the Virginia Company were granted the authority by Privy Council to coerce the “obstinate” into going. Similar orders for children to be sent to Virginia were fulfilled throughout the 1620s and a concomitant illicit “spiriting” of children from the Metropole continued well into the 18th century. The Privy Council’s response to this impasse in 1620 hinted at the future direction of centuries of penal transportation to the colonies, a practice not abolished until 1868.

The mortality rate in Virginia was high for all colonists at this time due to disease, hard labour, abuse and the many running battles with the Powhatan, the indigenous people whose land they were colonising. It is thus unknown how many of these transported children survived into adulthood. Those that arrived in the colony, perhaps thought of as apprentices for a trade back in England, were treated as indentured servants and could be put to any work that their master saw fit. Their contract, their ‘time’, was chattel personal, and until it was ‘served’ it was an asset that could be traded or left in wills.

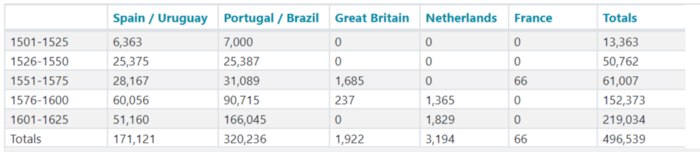

It is also worth noting that Jamestown 1619, despite its prominence on the contemporary cultural calendar, did not mark the first importation of enslaved Africans into the American colonies. According to the Slave Voyages database there were over 1,300 transatlantic slave trading voyages by European slavers from 1501 to 1619, involving circa 500,000 African victims.

The Motivation

The Canadian historian Donald Harman Akenson once wrote that “the real test of any mythology is not its accuracy — that is irrelevant — but whether or not it works.” Therefore having an awareness of the political motivation behind the ongoing dissemination of this “first slaves” propaganda and disinformation is as important as the fact-checking process itself.

The attempt by mainly right-wing reactionaries to negate the history and legacy of racial slavery in the United States is part of the relatively widespread adoption by the U.S. and European far-right of an exaggerated, weaponised and decontextualised “Irish were slaves, too” victimhood narrative. The “first slaves” iteration that this post focusses on is merely the most recent to achieve virality for the purpose of mocking or negating calls for, or even discussions about, reparations for slavery in America and the Caribbean. This memetic distortion of a very real history of suffering by Irish indentured servants and penal transportees in the 17th and 18th centuries is thus almost solely used for contemporary political, and often racist, purposes. For instance the first “white slavery” proto-meme on the world wide web dates back to 1999 when the Holocaust denier and white supremacist Michael Hoffmann published an image of three white child labourers from the early 20th century and captioned it “what about the white slaves?”

The first internationally reported use of the “Irish slaves” meme to negate the history and legacy of American slavery was when a member of the right wing Tea Party tweeted it in 2013. It’s important to note that this propaganda was disseminated on the 148th anniversary of the abolition of U.S. slavery. The motivation is thus always denialist in nature and such propaganda scheduling is akin to Neo-Nazis posting about the bombing of Dresden during a Holocaust anniversary. Indeed as I have shown over the past few years, this “whites were the first slaves in America” or “Irish were the first slaves” narrative is canon in white nationalist and Neo-Nazi literature. In 2014 the Neo-Nazi website The Daily Stormer used the same misappropriated image as @historylvrsclub to push this same propaganda.

It has grown dramatically in strength since then, peaking in popularity just prior to the U.S. presidential election of 2016 where it was used widely on social media to mobilise white victimhood sentiment, notions of racial superiority, the resentment of minorities and calls for racial justice.

Conclusion

Irish people were not enslaved in Colonial America, nor were they the first people indentured in Early Virginia. The claim that they were the “first slaves of America” is rated as false on both counts. It is evident that this false claim appropriates and distorts the history of the transportation in 1619 of one hundred poor English children who were sent from London to Virginia where they were to be bound out as apprentices.

As the historical geographer John Wareing surmised in his comprehensive study of Indentured Migration and the Servant Trade from London to America, 1618–1718, “indentured servitude was not chattel slavery” and thus it is a responsible practice to be specific about the terms we use in our effort to accurately identify and describe these different, but related, forms of unfree labour in the Early Modern Period. It is thus also a misleading claim in that it erroneously equates indentured servitude with chattel slavery.

Historically, many Irish and English people were forced into indentured servitude (bonded labour for a fixed period of time) in various Anglo American colonies during the Early Modern period via the imposition of severe poor law and criminal law which was to the benefit of colonial and mercantile interests who sought a cheap and tightly controlled labour force. This, along with the more predominate voluntary indentures from Britain and Ireland, was sometimes described by some contemporaries and its victims as being proximate to “slavery”.

But colonial indentured servitude was not equivalent or analogous to Anglo American slavery which was comprised of lifetime hereditary bondage based on race, nor does it predate that race-based enslavement practice which English colonists largely adopted from 16th century Iberian colonial slavery in the Americas and later ‘perfected’ as their colonisation of the continent intensified.

Verdict

Based on the What The Fact? scales guide, the claim is rated as False – the claim is inaccurate based on the best evidence publicly available at this time.

Selected Reading

Bailyn, Bernard, The Barbarous Years: The Peopling of British North America: The Conflict of Civilizations, 1600–1675 (New York, 2012), 84

Bremner, Robert H., Children and Youth in America: 1600–1865 (Harvard University Press, 1970), 6–8

Guasco, Michael, The Fallacy of 1619: Rethinking the History of Africans in Early America, Black Perspectives: African American Intellectual History Society, 4 September 2017

Guasco, Michael, Slaves and Englishmen: Human Bondage in the Early Modern Atlantic World (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2014)

Hogan, McAtackney and Reilly, The Irish in the Anglo-Caribbean: Servants or Slaves?, History Ireland, Vol. 24, Issue 2 (March 2016)

Hogan, Liam, Two years of the ‘Irish slaves’ myth: racism, reductionism and the tradition of diminishing the transatlantic slave trade, Beyond Trafficking and Slavery: openDemocracy (7 November 2016)

Kingsbury, Susan M. (ed.), The Records of the Virginia Company of London: The Court Book, from the Manuscript in the Library of Congress, Vol. III (Washington, 1933)

Neill, Edward D, History of the Virginia Company of London (New York, 1869),

Perry, James R., The Formation of a Society on Virginia’s Eastern Shore, 1615–1655 (University of North Carolina Press, 1990)

Raithby, John (ed.), The Statutes at Large, of England and of Great-Britain: From Magna Carta to the Union of the Kingdoms of Great Britain and Ireland, Vol. IV, 1553–1640 (London, 1811)

Voyages: The Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database, Emory Center for Digital Scholarship

Wareing, John, Indentured Migration and the Servant Trade from London to America, 1618–1718, “There is a Great Want of Servants” (Oxford University Press, 2017)

Wilkey, Robin, “Tea Party Leader’s Tweet Suggests Blacks Stop ‘Bitching And Moaning’ About Slavery”, Huffington Post, 18 December 2013

Wolfe and McCarthy, Indentured Servants in Colonial Virginia, Encyclopedia Virginia (28 October 2015) URL:

developmenteducation.ie’s What The Fact? supports the code of principles of the International Fact Checking Network. We check claims by influencers, from local to national to transnational that relate to human rights and international human development.

Transparent fact checking is a powerful instrument of accountability, and we need your help.

Send tips and ideas to facts@developmenteducation.ie

Join the conversation #whatDEfact on Twitter @DevEdIreland and Facebook @DevEdIreland

About

Liam Hogan is a librarian and historian based in Limerick, Ireland who is researching and writing about slavery, memory and power.

This post was posted with permission, based on Liam’s research series of posts which deconstruct images and memes circulating online about the Irish slave myth.

Explore the online exhibition with 100 objects providing a snapshot of Irish engagement with global cultural, political and social issues over the past 50 years.

More on developmenteducation.ie

Empathy – Who Cares Anyway?

Brighid Golden explores the concepts of sympathy, empathy and selective empathy and how to explore these in your teaching spaces.

3-point guide to Palestine and Israel for educators

In the shadow of the most traumatic attack on Jewish people since the Holocaust and what Palestinian people are referring to as a ‘second Nakba’, Ciara Regan shares a three-point guide for educators and teachers looking to make sense of the latest and most extreme clash of violence in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

Slow to Change, Quick to Greenwashing – case studies on fast fashion and fossil fuel adverts

What do fashion companies and EU lobbying have to do with greenwashing, but don’t know where to begin your learning journey? Part three in the series by Rachel Elizabeth Kendrick

Deniers, Delayers and Regulators, Oh My! Who’s involved in greenwashing?

Who is responsible and who is to blame for practices that can only amount to being called greenwashing? A teachers’ guide by Rachel Elizabeth Kendrick

A teachers’ guide to Greenwashing

A guidebook to support teachers and students in learning about greenwashing as a barrier to sustainable development.

Was Gary Lineker right about the British government’s refugee admissions?

What The Fact? Gary Lineker attends the training session at Fulham Football Club where refugee children take part on March 5, 2020. Photo by Hammersmith