Craig Allen’s challenge to the Fairtrade movement is a runner up blog in the 2015 Trinity College Dublin and developmenteducation.ie Development Issues blog series.

Fair Trade is envisioned as a modern mechanism that allows every day westerners to aid people in poorer countries by paying a “fairer” price for Fair Trade goods such as coffee, cotton or bananas. It’s different to aid or charity, because we’re helping others help themselves and allowing them to create a sustainable base to grow their communities and local economy.

On paper, that sounds excellent – exactly what Foreign Aid should be doing. So why is that a bad thing?

It Doesn’t Work

The Fair Trade movement is a bit like a child who puts a tortoise in deep water. All they’re trying to do is help, but they don’t realise that the tortoise can’t swim. When you explain this to them, they don’t understand because they have seen turtles swim and to the child’s mind, a turtle and a tortoise are the same thing.

In a similar way, the Fairtrade movement’s intentions are geared towards helping poorer farmers, but they don’t understand the deeper economic implications of their actions; that artificially raising prices only makes people worse off in the long run.

How does this happen?

Take a simple example: Rodrigo is paid €1 for each pound of Arabica coffee he makes.

The Fairtrade movement doesn’t think that’s enough and wants to pay Rodrigo €2 for a pound of Arabica coffee. Rodrigo now has double the amount of money compared to what he had before, so how can he actually end up having less?

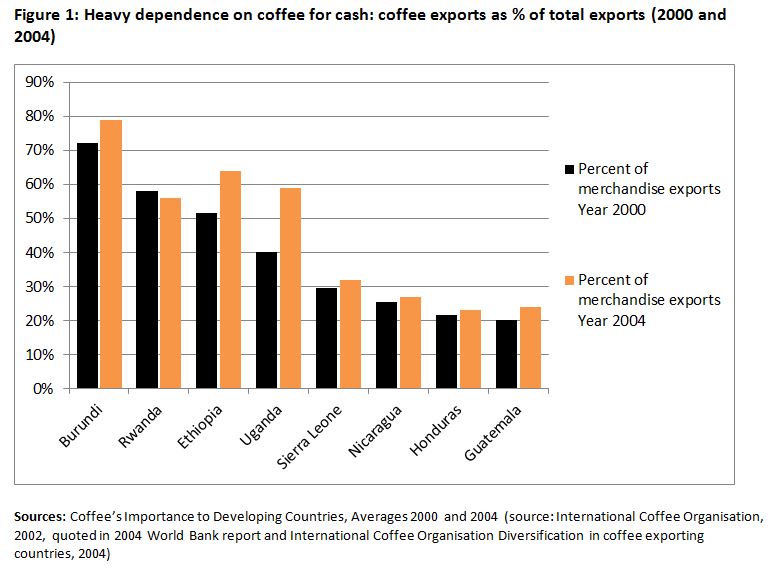

First, the setting of a price floor (paying a minimum price for goods) distorts world supply and demand. Now that coffee is worth more, there is a larger incentive for coffee growers to grow more of it (why sell eggs for €1 a pound when you can sell coffee for €2?).

This increases the world supply of coffee, but the increase in demand is artificial. Coffee growers outside of free trade schemes, therefore, and the coffee Rodrigo sells not under free trade will devalue. When there’s an oversupply of a good the price collapses (short briefing on this provided by Joe Leadbeater of Oxfam in 2003).

While Rodrigo will receive €2 for some of the coffee he sells the rest he may receive €0.50 for, and if you happen to be Hans, the coffee grower that lives next to Rodrigo, and don’t have a Fair Trade contract then you just receive the new actual market rate of €.50. Why? Because there’s a third guy, Jonas, who used to grow wheat for €1 a pound, but now that he thinks coffee can make him much more money, he switches production.

But there’s nobody to buy all the extra coffee – us westerners only want one Mocha Latte a day so the price for everyone falls because we end up with too much coffee. If all of your coffee is sold under Fair Trade then sure, you’re making more money, but all of your friends, and the community as a whole, are making a lot less.

An Adam Smith Institute report picked up by The Guardian in 2009 on ‘unfair trade’ concluded that Fairtrade is responsible for impoverishing non-Fairtrade farmers:

By guaranteeing a minimum price, Fairtrade also encourages market oversupply, which depresses global commodity prices. This locks Fairtrade farmers into greater Fairtrade dependency and further impoverishes farmers outside the Fairtrade umbrella. Economist Tyler Cowen describes this as the “parallel exploitation coffee sector”.

Why does this happen?

When Fair Trade started it had such a small impact on the market that these things weren’t a problem. If you go out and pay the local fruit seller double the odds because you think he deserves it then you’re not affecting any sort of global, or even local demand.

However, Fair Trade is now a billion dollar industry all by itself. Which means its actions have a knock on effect on the entire market.

By artificially increasing the demand, we make sure those regions produce as much coffee/bananas as possible and don’t produce other goods such as corn. This devalues the real value of the good (oversupply), leading to reduced income and can lead to an under supply of other goods (such as wheat/corn).

This can possibly benefit the wheat and corn farmer, but overall, it leads us to messing with the market rates of developing countries which, now that fair trade is a multi-billion dollar industry, can be quite drastic. I’m sure I don’t need to explain the effects of having a wheat shortage.

Fair Trade policies create a system that devalues the price of commodity goods worldwide.

It does, however, make the plethora of westerners who enjoy a nice warm cup of coffee on a cold weekday morning happy that they’re doing what they can to help poor in the best possible way.

It removes their guilt for exploiting those in other countries.

Fair Trade acts to ease the conscience of western consumers worldwide rather than making significant improvements in living standards across the developing world.

It’s a solution by the rich, for the rich and the only way to develop a serious system that helps those in poorer countries is to remove how “good” Fair Trade is from the western psyche and develop something entirely different that actually understands how the world markets work.

We need a knowledgeable adult, because as it stands, Fair Trade is an ignorant child.

………………………………

- The Trinity College Dublin development issues series is run in partnership with undergraduate students on the Democracy and Development course in the Department of Political Science and developmenteducation.ie

Explore more on developmenteducation.ie

Calling Post Primary Teachers – Survey Participation Request

Your voice is vital in shaping the future of education for sustainable development in Ireland. Join a national survey for post primary teachers in October, led by DCU researcher Valerie Lewis

Webinar: Science for development on World Food Day

The webinar will feature YSTE projects, from Santa Sabina Dominican College (Dublin), Moate Community School (Westmeath) and CBS Thurles that focussed on nutrition and better food production, with Self Help Africa’s nutrition and gender specialist in Ethiopia, Sara Demissew.

Student & teacher webinar: Food, hunger and SDG 2

Join the World Food Day webinar for post primary school students and teachers which will explore SDG 2, hunger in today’s world and how you can make a difference locally and globally.

Beth Doherty: Youth Activism and the Climate Crisis

From School Strikes to Global Climate Talks The latest episode of the Irish Global Solidarity in 100 Objects podcast features Beth Doherty, climate activist and

Mary Lawlor: Defending Human Rights Defenders

A Conversation with the UN Special Rapporteur for Human Rights Defenders The latest episode of the Irish Global Solidarity in 100 Objects podcast features Mary

Irish Women in Activism and Advocacy

Explore inspiring stories of Irish women in activism and advocacy who have fought for human rights, social justice, and equality at home and abroad