- Graphic: Martin Sanchez

We are all in it together. Some are just in deeper than others.

Rafael Behr, Guardian journalist, 10/3/21

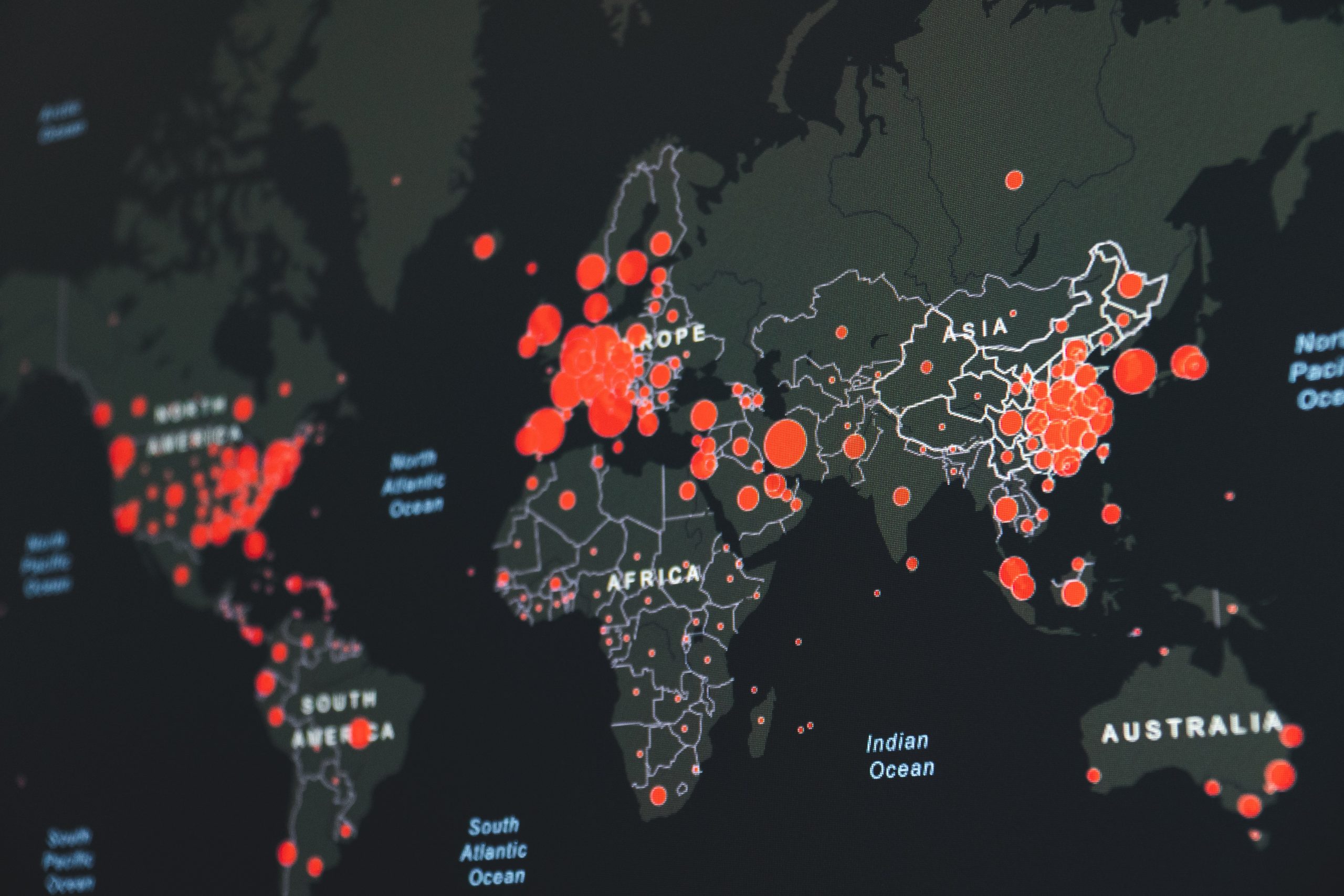

As I thought about where to start, I checked out the World Health Organization website for an overview of the current status of the pandemic. As of 9 March 2021, there have been 116.7 million reported cases of infection, 2.6 million deaths and 268 million doses of vaccine administered. The impact on individuals, families and communities has been devastating. A year ago I had no idea what Zoom was, social distancing meant avoiding boring relatives and lockdown happened in prisons to prevent riots.

When we weren’t out raiding the supermarkets for tinned goods and toilet rolls – I never quite understood why – we quickly adjusted to daily briefings and became expert observers of ‘R’ numbers, mutant strains and varied restriction levels.

Before we came to terms with the gravity of the situation, novelty face masks made their appearance. How effective they were at preventing the spread of infection I have no idea, but there were a few faces I would be glad to see wearing masks permanently.

If those opening paragraphs seem rambling and confused, then they comes close to describing my state of mind throughout. The threat of infection has affected all of us on a personal, family, community and global level. Millions of words have been written on the mental and physical health impacts, the effectiveness, or lack, of government and international responses and we are all becoming armchair experts on epidemiology and virology. For perhaps the first time in my life, we are facing a crisis which can affect anyone in a very immediate and critical way. But here’s the thing: most of us will avoid serious illness; many of us will avoid the economic hardship provoked by the lockdown restrictions on normal activity, not to mention the personal threat to the well-being of health workers and essential services of supermarket, transport and refuse collection workers.

So what can we, the average citizens who have been inconvenienced rather than harmed, learn from our experiences? And more importantly, what might we do differently to recognise the real value of key workers as well as prepare for the next crisis, medical, environmental, or both?

The selfless dedication of medical staff, the spontaneous response of local volunteers setting up resilience groups, the thousands who did the shopping for vulnerable elderly neighbours heartened me but didn’t really surprise me. The world has always worked best on the goodwill of ordinary people. Of course, we have all experienced stress to some degree and we will need advice and support to overcome “pandemic burnout”. In the noise around how levels of mental illness are rising, I found myself wondering if resilience and stress-busting should be included in the school curriculum.

In the early months, I became aware of some thinkers reflecting on the idea of “building back better”, the kind of neat slogan favoured by the UK’s cheer-leader in chief, Boris Johnson. I felt that this was worth taking seriously. As a person of faith, I was much encouraged by the statements of Pope Francis in particular, encouraging all of us to see this crisis as an opportunity to re-think how we do things. In the prologue to a very challenging and inspiring little book, Let Us Dream, he writes,

“To enter into crisis is to be sifted. Your categories and ways of thinking get shaken up; your priorities and lifestyles are challenged. You cross a threshold, either by your own choice or by necessity, because there are crises, like the one we’re going through, that you can’t avoid.

The question is whether you’re going to come through this crisis and if so, how. The basic rule of a crisis is that you don’t come out of it the same. If you get through it, you come out better or worse, but never the same.”

That’s an insight for all of us, not just Christians or people of faith in general.

As we have come through successive lockdown arrangements and the development of effective vaccines and therapies promise an eventual end to the pandemic, new challenges arise. The scientists advise that, until all of us have access to vaccination, none of us are safe. As the pharmaceutical companies scale up production and some countries seem to have greater priority of access to supplies, the squabbles over “vaccine nationalism” show all the signs of xenophobia and racism generally reserved for migrants. Despite attempts like the COVAX initiative to ensure vaccine availability for poorer countries, we are happy to take our priority place in the queue, knowing that it may be up to two years before some countries can hope to vaccinate their people.

In short, our response to the pandemic will reveal the strength of our commitment to global solidarity. This crisis will end, but you and I won’t be the same. Will that be a good thing for the future of humanity and the planet?

I received my first dose of vaccine in mid-February, so probably more immune to infection but not, I hope, to compassion. I am left with personal challenges and questions, possibly incurable. Perhaps the final comment should be another question, the final lines of a poem written in another time,

“Tell me, what is it you plan to do with your one, wild and precious life?”

More on developmenteducation.e

Beth Doherty: Youth Activism and the Climate Crisis

From School Strikes to Global Climate Talks The latest episode of the Irish Global Solidarity in 100 Objects podcast features Beth Doherty, climate activist and

Mary Lawlor: Defending Human Rights Defenders

A Conversation with the UN Special Rapporteur for Human Rights Defenders The latest episode of the Irish Global Solidarity in 100 Objects podcast features Mary

Irish Women in Activism and Advocacy: In Awe of All Mná

Explore inspiring stories of Irish women in activism and advocacy who have fought for human rights, social justice, and equality at home and abroad

Call for resource submissions open – education resources during an era of climate promises, disinformation and pandemics

Submit or recommend resources to be included in the Ireland-wide audit of development education and global citizenship education resources.

Podcast: If Another World Is Possible, It Is Up to Us to Make It So

A Reflection on Palestinian Solidarity and Collective Action In this episode of the Irish Global Solidarity in 100 Objects podcast, Ciara Regan revisits her 2021

Podcast: Exploring Global Citizenship with a Ball of String

The Power of Simple Tools in Teaching Global Citizenship Sometimes, the most impactful lessons come from the simplest tools. In this episode of the Irish