South Africa’s genocide case against Israel at the International Court of Justice, the Hague on Friday 12 January 2024. “ICJ South Africa v. Israel (Genocide Convention)”. Photo by ICJ is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

On December 29, 2023, South Africa filed suit at the International Court of Justice (ICJ), accusing Israel of genocide. South Africa has relatively limited economic and military resources. Its material power capabilities are comparable to those of small countries such as Malaysia or the Philippines, but the ICJ action is just the latest example of the country’s ability to act as a normative superpower, exceeding even the great powers in its capacity to shape the global moral discourse.

This proposition contradicts much recent commentary on the country’s international relations. In recent years, observers often argue that South Africa has lost its moral stature. Certainly, the South African government is falling short in its commitments to its citizens. The country suffers from tepid growth and inequality, unemployment, and poverty rates are extraordinarily high and rising. Moreover in the past few years, South Africa has been grappling with systematic cases of xenophobic harassment and massive deportations of undocumented migrants. The political leadership of the ruling African National Congress (ANC) has done much to undermine the country’s reputation, with widespread political abuse and corruption at home, and cozy relationships with autocratic, lawless regimes abroad. But the legacy of Mandela’s global moral leadership continues. South Africa has consistently played a determining role in the construction of international norms.

During apartheid, the world coalesced to condemn it. The country became a pariah, suspended from the United Nations. When apartheid fell, however, South Africans radically redefined its role in international politics. The salience of the international anti-apartheid movement gave the state an opportunity to ride a wave of goodwill. In his famous “I am an African” speech, then deputy president Thabo Mbeki addressed the complexities of South African identity, asserted its special place in the global struggle against racism and colonialism, and gestured toward its historical mission bringing what he would soon be calling an “African renaissance” to the world.

Notwithstanding its subsequent limitations, this was a rousing vision for a rising normative superpower. Putting this vision to work, the country moved to position itself as a regional power and a leading player in issues of global importance. Its 1999 White Paper on Peacekeeping asserted that:

Domestic and international expectations have steadily grown regarding a new South African role as a responsible and respected member of the international community. These expectations have included a hope that South Africa will play a leading role in a variety of international, regional and sub-regional forums, and that the country will become an active participant in attempts to resolve various regional and international conflicts.

In the early post-apartheid era, the country quickly caught up with international organizations. It became a member of several UN bodies and groups, such as the Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM), and the G77. Honoring the support it received from the NAM and the UN during apartheid, the ANC embraced multilateralism and committed to reforming the Western rules-based order from within. But even in these halcyon years, the South African government revealed a dissonant streak, refusing to condemn Nigerian human rights violations in 1995 and using military force to quell a coup in Lesotho in 1998 without prior UN approval.

On balance, however, the South African government cultivated an image of international neutrality and leadership. The memorably monikered “Rainbow nation” consciously leveraged its peculiar demographic, political, and economic fusion of East and West, North and South, to construct a bridge between the developed and developing worlds. These extraordinary endowments, often prudently mobilized, were not so readily available to other emerging powers. Those who might have outcompeted South Africa in its bid for moral hegemony—including China, India, Indonesia, Brazil, Argentina, Egypt, and Russia—lacked South Africa’s easy interlocution of diverse global perspectives and traditions. They sometimes descended into rogue status. Otherwise, they were too focused on domestic and regional issues, lacking South Africa’s sense of global moral purpose.

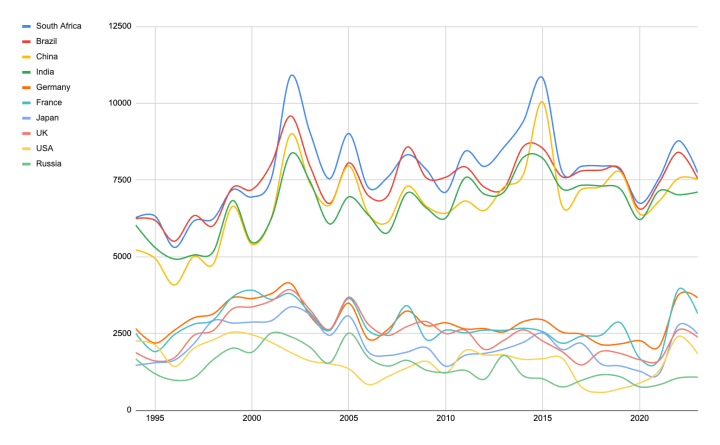

It is plausible that South Africa’s active engagement in norm-making is also an effort at so-called “soft balancing.” The country’s material weaknesses make it vulnerable as a regional power vis-à-vis other regional powers. In BRICS, for instance, South Africa has been grouped alongside countries with far greater material power resources, including Brazil, Russia, India, and China. But despite this power gap, as Japanese scholar Tomoko Takahashi has found, South Africa is more active in regional organizations and the UN than its peers. South Africa has also been more successful, mobilizing its diplomatic resources to foster diverse international networks and reshape the rules of the game in its favor.

The country’s early induction into BRICS itself is one indicator of its ability to punch above its weight. South Africa has become a major mediator of conflicts across Africa, helping to ameliorate violent disputes in Angola, Burundi, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, the Comoros, Ethiopia, the Ivory Coast, Kenya, Madagascar, and Mozambique. In 1995, it also played a major role in persuading reluctant countries to sign the extension of the Treaty on Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons. Mandela was also very active in boosting the ban on anti-personnel mines, and during its first term as a non-permanent member of the UN Security Council in 2007-2008 South African diplomats managed to pass a resolution to strengthen the role of the African Union in handling regional conflict and contributed to peacekeeping forces in Sudan. In the process, South Africa has been able to position itself as a vital link between Africa and the world.

South Africa’s successes can also be measured with data. In the years between 1994 and 2023, the country persistently accumulated more co-authorships and sponsorships of UN General Assembly resolutions than more powerful countries. Great powers such as China, Russia, Great Britain, Germany, Japan, and the US have generally not attained even half of South Africa’s figures.

This relative success puts South Africa’s ICJ suit into perspective. Undoubtedly, the country’s gravitation toward the BRICS countries exposes it to moral criticism. South Africa will find it increasingly difficult to maintain its moral standing in the increasingly complex geopolitics of the world. Already, it has been harshly criticized for abstaining from voting to condemn Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and the ethnic cleansing of Rohingya Muslims in Myanmar. These failures portray the country as an ally of Russia and China, but South Africa still carries global normative heft. The country has been instrumental in mobilizing most of the nations of the world behind its daring action of suing a powerful country, which is steadfastly backed by the US. This move carries considerable potential for impacting the course of US domestic politics and reshaping its global rules-based order. These are no longer years of the Cold War, when less powerful countries had limited means of contestation and options to check the unilateral actions of great powers.

South Africa can exploit its brokerage power in the Global South to strengthen cooperation with other less powerful regional leaders such as Indonesia, Colombia, and Chile to collectively advance norms that revise the Western-led system of global governance beyond bipolar and multipolar great power competition. The moral stature of such a coalition likely garners enough support of other Global South countries to revive the spirit of the NAM, and the ICJ suit may be just the beginning. The vision of an African renaissance lives on.

- Juan Acevedo-Ossa is a research associate at the Ralph Bunche Institute and a PhD student at the Graduate Center, City University of New York

- This article was orginally published on Africa is a Country in January 2024. See original article here.