What The Fact?

Factsheet: Violence against women and the 'Shadow Pandemic'

On Monday 6 March 2018, Mexico City woke up to an artistic installation consisting of a number of signs of Venus – representing women – intending to stress the magnitude of femicidal violence, and the need to eradicate it. Photo by Photo: UN Women/Dzilam Mendez (via Flickr CC-BY-NC-ND)

- Aoife McDonald

What’s the ‘Shadow Pandemic’? Has there really been a global surge in gender-based violence against women and girls? A factsheet, by Aoife Mc Donald.

1. What is the 'Shadow Pandemic’?

Since the beginning of the Covid-19 pandemic, there has been a global surge in gender-based violence (GBV) against women and girls, which has been called ‘the Shadow Pandemic’.

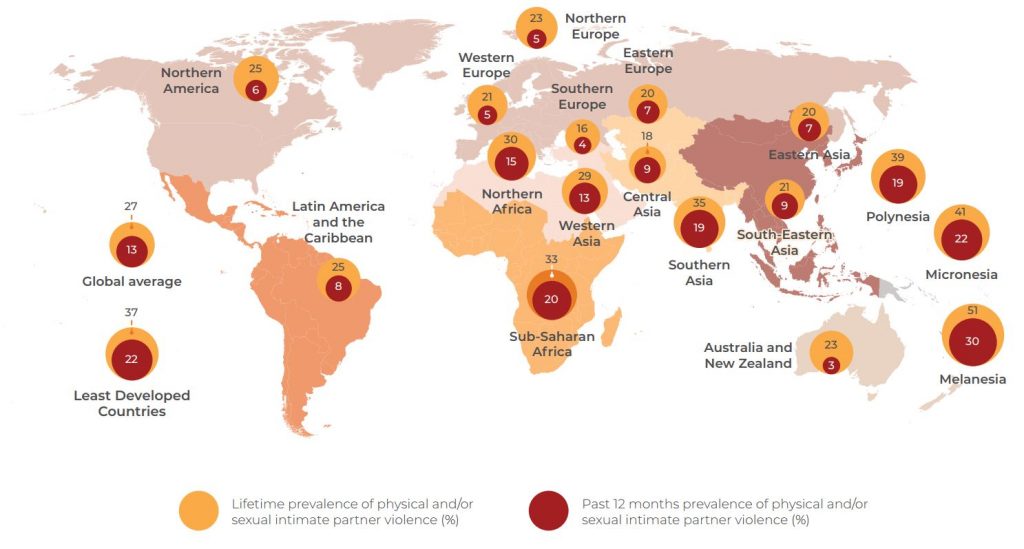

According to UN Women, an estimated 736 million women (30 per cent of women aged 15 and older) have been subjected to intimate partner violence, non-partner sexual violence, or both at least once in their life. Lockdowns, economic hardship, school closures and restricted movement have all fuelled the surge in GBV globally, prompting 121 countries to strengthen services for women survivors of violence.

2. What forms does gender-based violence take?

The UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR) defines GBV as

“harmful acts directed at an individual based on their gender. It is rooted in gender inequality, the abuse of power and harmful norms”.

GBV is not limited to physical and sexual violence; it can include mental and economic harm, as well as threats of violence, coercion and manipulation.

GBV can take a variety of forms: intimate partner violence (also called domestic violence), sexual violence and harassment, online violence, forced marriage and female genital mutilation, among others. The majority of this violence is at the hands of an intimate partner. As many as 38% of all murders of women, worldwide, are committed by intimate partners.

Intimate partner violence is worst in “least developed countries” or low income countries, where 22 per cent of women have been subjected to intimate partner violence in the past 12 months, in comparison to the world average of 13 per cent.

3. How has Covid-19 exacerbated these types of violence?

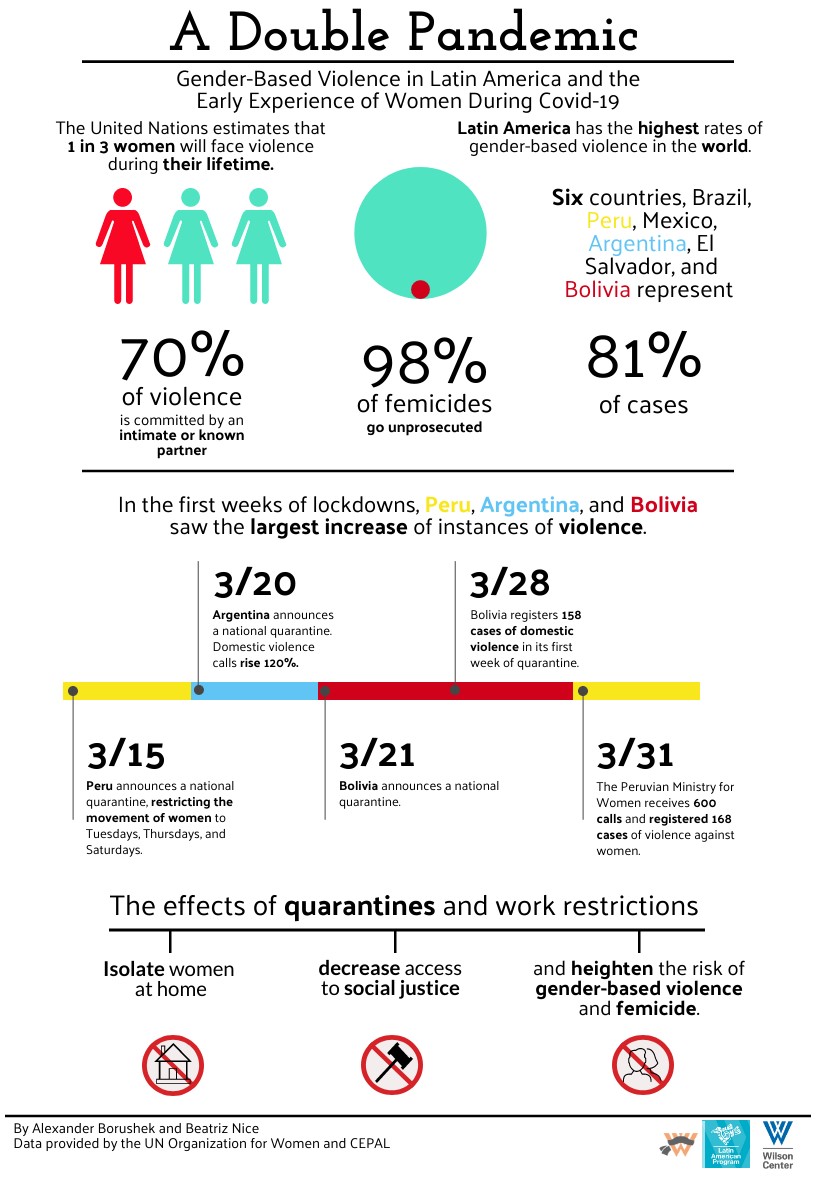

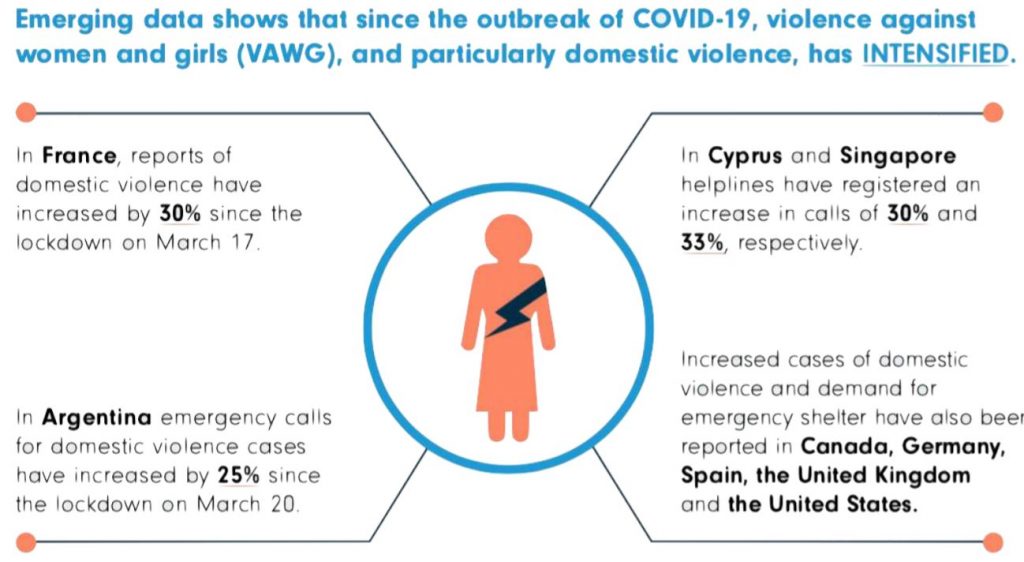

Globally, the pandemic triggered a rise in cases of intimate partner violence, as quarantine measures leave victims isolated with their abusers. At least 15 million more cases are being reported for every three months of imposed lockdowns. In France, for example, cases of intimate partner violence have increased by 30 per cent since March 2020, while emergency calls for domestic violence in Argentina have increased by 25 per cent.

In Peru, more than 5,521 women were officially recorded as missing in 2020. Previously, 5 women went missing a day in Peru, which has increased to 8 a day. The pandemic has worsened an already dire problem.

In the Philippines and India, COVID-19 restrictions have emptied public spaces, increasing the fear and the experience of violent attacks.

School closures have left girls open to sexual violence from family, neighbours and community members. Kenya, Malawi and Ethiopia are reporting spikes in teen pregnancies and early marriages, increasing the likelihood that girls will not return to school, in turn reversing decades of progress in tackling gender inequality.

In developing countries, social and economic strains have made women and girls more vulnerable to sexual exploitation, child marriage and human trafficking. With families unable to earn an income, many girls are being forced into transactional sex in order to survive.

From Kenya, Somalia and Tanzania in the east to Liberia, Sierra Leone and Nigeria in the west, the COVID-19 pandemic has led to a surge in reports of girls across Africa undergoing female genital mutilation (FGM), according to reports from many women’s rights groups. Families are performing FGM on young daughters in the hope of marrying them off to ease the financial burden.

Finally, a rise in the use of online platforms since the start of the Covid-19 pandemic has been accompanied by a rise in stalking, bullying, sexual harassment, and sex trolling online. According to Europol, online activity by those looking for child abuse material has also increased in the EU.

4. What is being done?

The Shadow Pandemic has provoked a variety of responses around the world. On a local level, hotels in France are providing alternative accommodation for domestic violence survivors as shelters exceed capacity. In Spain, Italy and France, women can alert pharmacies about domestic violence with the code “mask-19”, allowing pharmacies to contact police. In Guatemala, flags have become common across the country to signify different needs: black, yellow or blue shows that a woman, child or elderly person is in danger of violence.

On a national level, Côte d’Ivoire, Honduras and Tunisia increased funding and resources for the expansion of helplines and shelters for the survivors of violence. Other countries, like China and South Africa, are using virtual means to keep the justice system operating, to avoid backlogs in cases and to ensure perpetrators of violence are being convicted.

On a global level, UN Women has a Covid-19 and Gender Monitor which provides gender-disaggregated data on the pandemic to inform gender-responsive policy from national governments. The UN ran the 16 days campaign against GBV in November 2020 to call governments to action on the Shadow Pandemic.

Nonetheless, these efforts have had minimal effect on the Shadow Pandemic worldwide, which threatens to reverse hard-won strides toward gender equality. And certain governments have even taken advantage of the global emergency to restrict women’s rights. In Turkey, for example, President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan has made the decision to withdraw Turkey from the Istanbul Convention, a Council of Europe treaty to prevent and combat violence against women. Women across the country are calling for a reversal on the decision before official withdrawal on the 1st of July.

The Covid-19 pandemic has revealed the structural inequalities that allow gender-based violence to flourish in a crisis. The eradication of this type of violence requires deeper reforms, addressing political, economic and social inequalities as well as harmful gender norms.

Aoife Mc Donald is a master’s student in International Relations at University College Dublin and research intern with 80:20 Educating and Acting for a Better World

developmenteducation.ie’s What The Fact? supports the code of principles of the International Fact Checking Network. We check claims by influencers, from local to national to transnational that relate to human rights and international human development.

Transparent fact checking is a powerful instrument of accountability, and we need your help.

Send tips and ideas to facts@developmenteducation.ie

Join the conversation #whatDEfact on Twitter @DevEdIreland and Facebook @DevEdIreland

Explore more on developmenteducation.ie

From Nicaragua to Ireland: Fairtrade Coffee and Global Solidarity

Fátima Ismael of Soppexcca, Cathal Murphy from Bewley’s and Fairtrade practitioner Kieran Durnien discuss 20 years of Fairtrade coffee solidarity linking Nicaragua and Ireland.

Critical Thinking for Global Citizenship Education

Join Brighid Golden for the launch of her latest book, ‘Critical Thinking for Global Citizenship Education: A Conceptual Framework’

Your voice matters – 2026 user survey open

It’s January, its 2026, and we want to hear what you’d like us to feature or work on in 2026.

Calling Post Primary Teachers – Survey Participation Request

Your voice is vital in shaping the future of education for sustainable development in Ireland. Join a national survey for post primary teachers in October, led by DCU researcher Valerie Lewis

Webinar: Science for development on World Food Day

The webinar will feature YSTE projects, from Santa Sabina Dominican College (Dublin), Moate Community School (Westmeath) and CBS Thurles that focussed on nutrition and better food production, with Self Help Africa’s nutrition and gender specialist in Ethiopia, Sara Demissew.

Student & teacher webinar: Food, hunger and SDG 2

Join the World Food Day webinar for post primary school students and teachers which will explore SDG 2: Zero Hunger.