How many people are struggling to overcome hunger in the world today are we on track to achieve zero hunger by 2030? Colm Regan presents 5 key takeaways from the 2020 Global Hunger Index and the State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World reports.

- World Food Day 2020 materials and coverage – a series in partnership with Scoilnet, Concern Worldwide, Self Help Africa and developmenteducation.ie

Taken together, these two key reports offer you most of what you need to know on this important topic. Both are readily accessible with data, case studies, tables and maps. They can readily be used in educational contexts and can be downloaded free.

As part of our contribution to World Food Day 2020, developmenteducation.ie has summarised 5 key messages or ‘takeaways’ from these two reports.

Report 1: Starting in 2006, the non-governmental organisations Concern Worldwide (Ireland) and Welthungerhilfe (Germany) have jointly researched and published the annual Global Hunger Index.

The report tracks the state of hunger world-wide and highlights key issues as well as places where action to address hunger is most urgently needed.

The 2020 report is called 2020 Global Hunger Index: One Decade to Zero Hunger: Linking Health and Sustainable Food Systems.

Report 2: each year the UN Food and Agriculture Organisation publishes the State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World Report and is considered by most analysts as one of the most authoritative reports.

The 2020 report’s theme is ‘transforming food systems

1. An estimated 2 billion people did not have regular access to safe, nutritious and sufficient food in 2019

On the data

Currently an estimated 690 million people are hungry, or 8.9% of world population – 10 million more than in 2019 and nearly 60 million more in the last 5 years. In 2019, close to 750 million – or nearly one in ten people in the world – were exposed to severe levels of food insecurity which is another measure that approximates hunger also an upward trend.

In addition an estimated 2 billion people did not have regular access to safe, nutritious and sufficient food in 2019.

Initial assessments suggest that COVID-19 may add between 83 and 132 million people to the total number of undernourished in 2020 depending on what happens with economic growth. The world is not on track to achieve Zero Hunger by 2030 as agreed in the SDGs. If recent trends continue, the number of people affected by hunger would surpass 840 million by that date.

2. Progress has been made but it is not guaranteed into the future

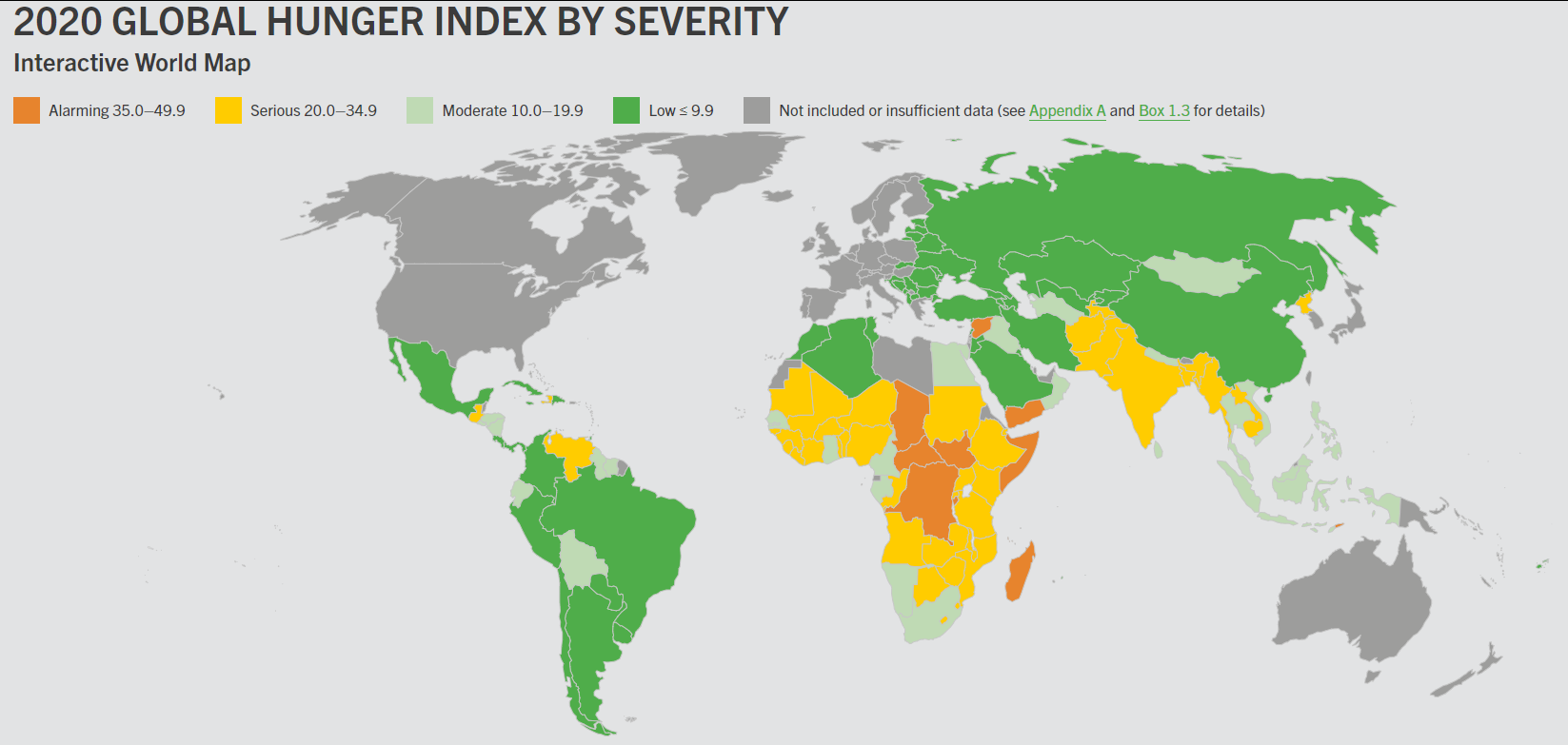

On the geography of hunger

Of the 2 billion people suffering from food insecurity, 1.03 billion are in Asia, 675 million in Africa, 205 million in Latin America and the Caribbean, 88 million in Northern America and Europe, and 5.9 million in Oceania

While hunger is considered ‘moderate’ globally, it varies widely by region.

- In both Africa South of the Sahara and South Asia, hunger is classified as ‘serious’ as large shares of people are undernourished and where there are high rates of child mortality, child stunting and child wasting

- In Europe and Central Asia, Latin America and the Caribbean, East and Southeast Asia, and West Asia and North Africa are described as ‘low or moderate’ but hunger is high among certain groups within these regions.

‘Alarming’ levels of hunger have been identified in 3 countries (Chad, Timor-Leste, and Madagascar) and ‘potentially alarming’ in another 8 (Burundi, Central African Republic, Comoros, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Somalia, South Sudan, Syria, and Yemen) and is deemed ‘serious’ in an additional 31 countries.

In 14 countries (across different regions) the prevalence of undernourishment is between 25% and 50% indicating that one-quarter to one-half of the population faces chronic hunger (see notes below).

The child stunting rates in 35 countries exceed 30%, the level at which they are considered ‘very high in terms of public health. The 10 highest rates are in Burundi, Yemen, Timor-Leste (54% – 51%), Niger, Guatemala (48% – 47%), Mozambique, Democratic Republic of the Congo Madagascar, Papua New Guinea and Chad (42% – 40%).

Overall and without taking into account the effects of COVID-19, projected trends in undernourishment would change the geographic distribution of world hunger dramatically. While Asia would still be home to almost 330 million hungry people in 2030, its share of the world’s hunger would shrink substantially. Africa would overtake Asia to become the region with the highest number of undernourished people (433 million), accounting for 51.5% of the total.

It is important to remember that progress has been made in the past in many parts of the world, providing hope for the future. Looking back over the past 10 to 20 years, most countries have experienced improvement, even in countries where hunger and undernutrition were considered ‘extremely alarming’ 20 years ago, the situation has improved dramatically.

3. Healthy diets are unaffordable for more than 3 billion people, especially the poor, in every region of the world

Health and diet

To ensure the right to adequate and nutritious food for all and to end hunger by 2030, we must not only reshape our food systems to become fair, healthy, resilient, and environmentally friendly but also integrate them into a broader political effort to maximize the health of humans, animals, and our planet” – Global Hunger Index 2020, p.51

Healthy diets are now unaffordable to many people, especially the poor, in every region of the world. The most conservative estimate shows they are unaffordable for more than 3 billion people in the world.

Healthy diets are estimated to be, on average, five times more expensive than diets that meet only dietary energy needs through a starchy staple. The cost of a healthy diet exceeds the international poverty line (set by the World Bank at US$ 1.90 purchasing power parity per person per day), making it unaffordable for the poor.

The cost also exceeds average food expenditures in most countries in the Developing World: around 57% or more of the population cannot afford a healthy diet throughout sub-Saharan Africa and Southern Asia.

All diets have hidden costs – two such costs that are most critical relate to the health and climate-related consequences of dietary choices and the food systems that support these. Under current food consumption patterns, diet-related health costs linked to mortality and non-communicable diseases are projected to exceed US$ 1.3 trillion per year by 2030. On the other hand, the diet-related social cost of greenhouse gas emissions associated with current dietary patterns is estimated to be more than US$ 1.7 trillion per year by 2030.

4. We are hitting planetary and social boundaries - that is, the ecological ceiling and the social foundation beyond which humans cannot safely and equitably thrive - and our food systems are part of the problem

Broken Food Systems

The current situation requires that we act to reshape our food systems to make them fair, healthy, and environmentally friendly so that we can address the current crises, prevent other health and food crises from occurring and plan a way to achieve Zero Hunger by 2030.

We are now reaching planetary and social boundaries – that is, the ecological ceiling and the social foundation beyond which humans cannot safely and equitably thrive – and our food systems are part of the problem. They pose health hazards to humans and the environment and have a big part in the rise of emerging infectious diseases such as COVID-19. Through land use changes, intensive agriculture, large-scale livestock production and other practices, food systems have led to agro-ecological degradation, destroyed habitats, and contributed to climate change, it contributes between 21% and 37% of total net human-caused emissions of greenhouse gases and accounts for 70% of freshwater use.

We are hitting planetary and social boundaries – that is, the ecological ceiling and the social foundation beyond which humans cannot safely and equitably thrive – and our food systems are part of the problem.” – Global Hunger Index 2020, p.24

Our food systems are inherently unequal and further exacerbate inequities; global food control is tilted against low-income countries and against smallholder farmers. Lack of secure land tenure and resulting food insecurity are a persistent issue for rural communities, indigenous people, women, and marginalised groups.

Other challenges include the fact that formal and informal education on agriculture, nutrition and related issues is not sufficiently suited local conditions; social protection schemes remain insufficient or misdirected. Also our inadequate emergency responses are disrupting local food systems and fail to support local producers.

Some actions must be taken immediately, such as treating the production and supply of food as essential services and involving community organizations to extend the reach of social protection programs. Others must be tackled including eliminating inequitable trade and investment arrangements that hold back low- and middle-income countries and working toward a circular food economy that recycles resources and materials, regenerates natural systems, and eliminates waste and pollution.

5. Covid-19: There is sufficient food, but millions are at risk

COVID-19’s potential impact

The COVID-19 pandemic is impacting everyone and is also damaging the world economy reducing people’s capacity to access healthy diets. Record levels of unemployment, lost livelihoods and rising poverty levels will cause healthy diets to become even more unaffordable for the more than 3 billion people noted in these reports. There is sufficient food, but millions are at risk of not having access to diverse and nutritious foods. Border closures, quarantines, market, supply chain and trade disruptions are restricting people’s physical access to sufficient, diverse and nutritious sources of food, especially in countries hit hard by the pandemic or already affected by high levels of food insecurity.

Food losses are increasing (especially of fruits and vegetables, fish, meat and dairy products) as food supply chains come under strain; food production, processing, trade and transportation networks and access to food markets and retail outlets are restricted. Food prices may also rise in the absence of urgent and coordinated policy measures and corrective action.

In countries hardest hit there has been a reduction in the demand for fruits, horticultural and other perishable products, such as aquatic products, leading to a decline in food prices. The poultry and egg food production chains have also faced strong downward price pressures.

Migrant workers, their families and communities have been affected by lockdowns, trade disruptions, layoffs and illness, while their capacity to send remittances to their home countries has dropped significantly.

The Global Hunger Index measures hunger in 4 dimensions:

- Undernourishment – the share of the population that is under-nourished (that is, whose caloric intake is insufficient)

- Child Wasting – the share of children under the age of five who are wasted (that is, who have low weight for their height, reflecting acute undernutrition)

- Child Stunting – the share of children under the age of five who are stunted (that is, who have low height for their age, reflecting chronic undernutrition)

- Child Mortality – the mortality rate of children under the age of five (in part, a reflection of the fatal mix of inadequate nutrition and unhealthy environments).

What is meant by ‘hunger’?

The problem of hunger is complex, and different terms are used to describe its various forms.

Hunger is usually understood to refer to the distress associated with a lack of sufficient calories. The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) defines food deprivation, or undernourishment, as the consumption of too few calories to provide the minimum dietary energy an individual requires to live a healthy and productive life, given that person’s sex, age, stature, and physical activity level.

Undernutrition goes beyond calories and signifies deficiencies in any or all of the following: energy, protein, and/or essential vitamins and minerals. Undernutrition is the result of inadequate intake of food in terms of either quantity or quality, poor utilization of nutrients due to infections or other illnesses, or a combination of these immediate causes. These, in turn, result from a range of underlying factors, including household food insecurity; inadequate maternal health or childcare practices; or inadequate access to health services, safe water, and sanitation.

Malnutrition refers more broadly to both undernutrition (problems caused by deficiencies) and overnutrition (problems caused by unbalanced diets that involve consuming too many calories in relation to requirements, with or without low intake of micronutrient-rich foods). Overnutrition, resulting in overweight, obesity, and noncommunicable diseases, is increasingly common throughout the world, with implications for human health, government expenditures, and food systems development. While overnutrition is an important concern, the GHI focuses specifically on issues relating to undernutrition.

In this the Global Hunger Index reports, “hunger” refers to the index based on the four component indicators. Taken together, the component indicators reflect deficiencies in calories as well as in micronutrients.

Source: Global Hunger Index 2020

For more

Water is life! World Food Day round-up 2023

The World Food Day round-up includes new features and interactives for teaching and learning based on key drivers of world hunger today.

Access to or lack of? Food insecurity in 2022 – an update

An additional 345 million people are food insecure. How did this happen? Navika Mehta reviews the latest global food security report

World Food Day round-up

The World Food Day round-up includes new features and interactives for teaching and learning based on key drivers of hunger today