Farming in Biatorbágy, Szily Kálmán in Hungary, January 16, 2019. Photo by Bence Balla-Schottner on Unsplash

An additional 345 million people are food insecure. How did this happen? Navika Mehta reviews the latest flagship global food security report.

Hunger is a word used on a daily basis or its variations – hungry, hangry, famished or even starving. It’s a feeling most people would claim to be familiar with, however, the hunger and starvation that is widespread in many regions of the world is very different from this temporary feeling.

This hunger is parents sending children to school so they can have one meal a day offered through government initiatives. It’s hundreds of people standing in long queues to access subsidised grains that are very easily robbed by intermediaries. It’s the rapidly increasing price of basic ingredients like onions after they are hoarded by those who wish to profit from this hunger. It’s the politicians who make empty promises of ensuring food security during elections and once elected talk about building highways instead.

This past year, food security for millions of people is under threat with an increase in the number of people affected by hunger across the world, particularly in Asia and Africa where inequalities across and within countries are heightened.

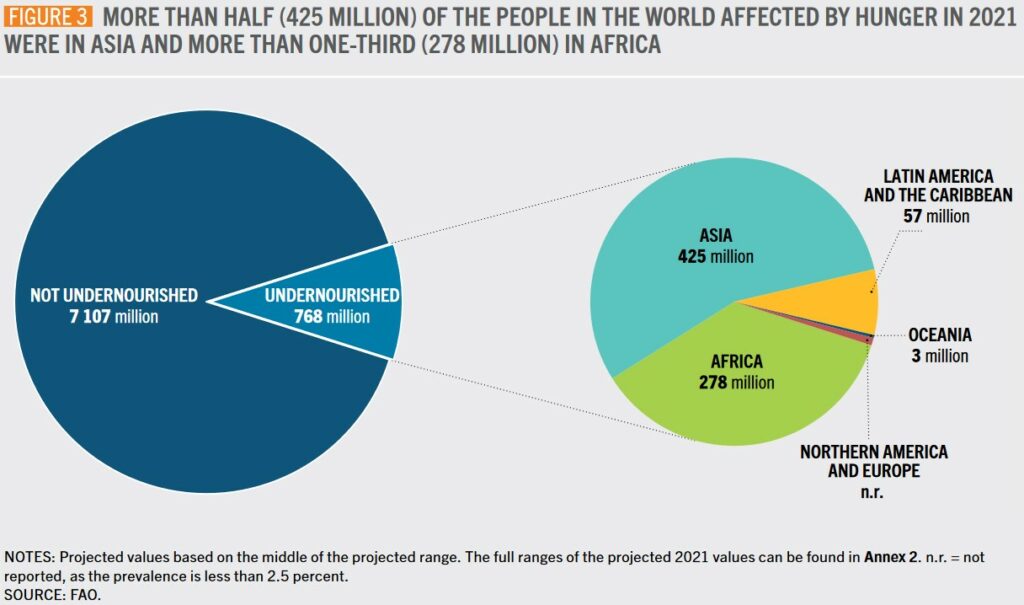

The 2022 update from UN Food and Agriculture Organization’s (FAO) annual The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World report, more than half of those affected by hunger are in Asia and more than one-third are in Africa. Countries that have low-incomes have a higher burden as a larger proportion of people who are severely food insecure compared to high-income countries.

“This year’s report should dispel any lingering doubts that the world is moving backwards in its efforts to end hunger, food insecurity and malnutrition in all its forms. We are now only eight years away from 2030, the SDG target year. The distance to reach many of the SDG 2 targets is growing wider each year, while the time to 2030 is narrowing.

There are efforts to make progress towards SDG 2, yet they are proving insufficient in the face of a more challenging and uncertain context.”

A common misconception, when talking about food security, is that there is a lack of food available. The real problem is accessibility to food. There is enough to feed the planet adequately, yet food waste and harmful agricultural practices make food inaccessible. This food insecurity is then reflected in the economic inequalities across the globe.

Setbacks in tackling food insecurity and inequality across regions

This inaccessibility of food is further increased by geo-political and climate change challenges.

Following the consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic on international supply chains and the ongoing war in Ukraine, disruption of food supply, fuel, fertiliser markets, inflation and trade restrictions have severely impacted global food trade.

Only in August this year, following the reopening of Ukraine’s Black Sea Port, the first maritime shipment of Ukrainian wheat grain left for humanitarian operations run by the UN World Food Programme in the Horn of Africa and Yemen, a drought-hit region. Intense flooding in Pakistan affected more than 33 million people along with loss of homes, livestock and damage to infrastructure and agricultural land.

According to the FAO report, around 2.3 billion people were moderately or severely food insecure in 2021: that is 30% of the global population.

The rate of severe food insecurity has increased between 2019 to 2021. The report notes:

- The gender gap in food security has widened with 31.9% women being moderately or severely food insecure compared to 27.6% men.

- The Food Price Index shows the monthly change in the international prices for a basket of food commodities. This index, while falling at a consistent rate across years, now continues to increase since July 2021. It’s interesting to note that the food insecurity levels and food price index are not necessarily interconnected. Food insecurity may be a consequence of climate change, rise in population and other factors which may not have a great impact on the food price index.

- Since the COVID-19 pandemic, inequalities in terms of pace of growth of countries are also uneven. While high income countries have managed to recover their GDP growth, lower and lower-middle-income countries are much slower.

- Workers from underrepresented and disadvantaged groups are worse affected after the COVID-19 pandemic. This is evident as for the first time in 20 years there has been an increase in global extreme poverty and income inequality.

Russian Invasion of Ukraine

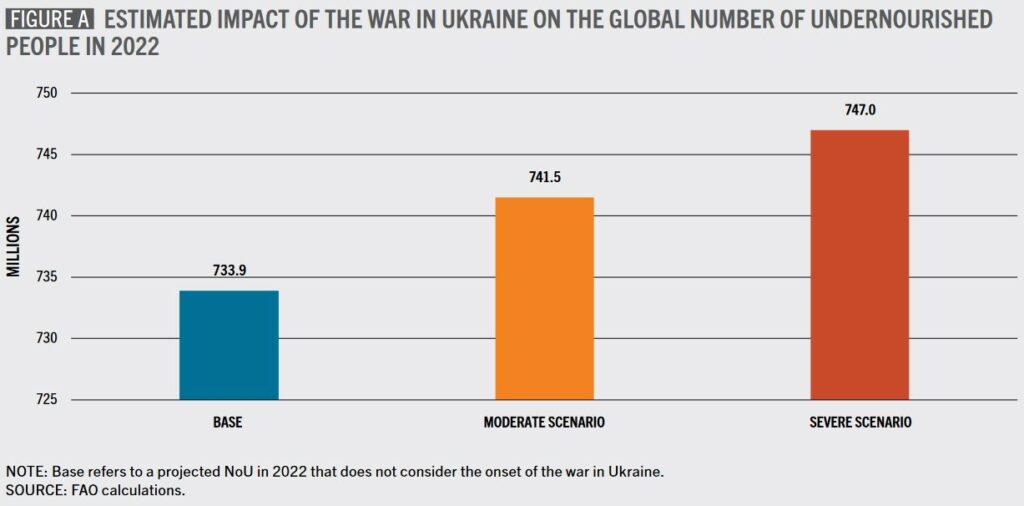

The war in Ukraine has forced massive displacement of people across the world. It has also caused a disruption in food supply with 30% of the population who depend on agriculture for livelihood affected.

Shortages along with damage to land, people, infrastructure and other inputs has contributed to food insecurity in the region. Not only neighbouring countries, but also countries around the world are facing shortages as Russia and Ukraine are important producers of cereal, oil seeds, cooking oil, fuel and fertilisers.

Many low and middle income countries depend on Ukraine and Russia for food supplies and are now facing the negative effects of higher prices.

The reduced supply of food from Ukraine and Russia is adding further strain on the international food commodity prices. The World Bank has estimated that remittances from migrant workers in Russia could reduce by 25%. The countries that the workers belong to, depend on this income to a large extent. In response to the war, FAO’s Rapid Response Plan assists vulnerable households through cash transfers and agricultural interventions.

For organisations like the FAO and UN World Food Programme, providing humanitarian relief in conflict areas poses further challenges.

In Haiti, for example, the school feeding programme is on hold because of the political situation in Port Au Prince making it unsafe for children to attend school. Warehouses containing food stocks have also recently been attacked by desperate protesters who are facing unprecedented hunger levels along with high inflation.

Climate change challenges

While countries in Europe witnessed heat waves and high temperatures over the summer, many parts of Africa including Gambia, Chad and Burkina Faso saw heavy flooding in some regions and droughts in others. This has led to an increase in food prices.

In Mauritania, wheat is 49% higher in price and in Sierra Leone, imported rice is 87% more expensive.

The World Food Programme aims to set up warning systems to prepare for climate disasters before they occur. They work to build resilience using farming techniques and infrastructure along with climate-insurance programmes to help countries affected by climate change to recover.

In Niger, for example, a project for digging half-moons in the ground helps retain rainwater and fight desertification. It recovers desert lands and preserves crops. Techniques like these can serve to be useful and provide faster relief while countries negotiate emission levels

A joint statement by the leaders of FAO, the International Monetary Fund (IMF), World Bank, World Food Programme (WFP) and the World Trade Organization (WTO) argues that the current geo-political situation and disruption of food supply chains internationally has contributed to the increase in the number of food insecure people to 345 million across 82 countries.

Furthermore global food trade has been impacted by countries responding to higher food prices using export restriction policies. There is an urgent need to provide support to vulnerable households, ensuring the trade and international supply of food, increasing sustainable food production across the world and investing in climate-resilient agriculture.

Without long-term sustainable actions aimed towards effectively facilitating trade and production of food that is accessible, the number of food insecure people will continue to rise.

- Navika Mehta is a Teaching Fellow in Economics at Trinity College Dublin. She is an activist who campaigns to end racism and Direct Provision.

This post is brought to you as part of the World Food Day 2022 series – an editorial partnership with Scoilnet, Concern Worldwide, Self Help Africa and developmenteducation.ie

More on developmenteducation.ie

Beth Doherty: Youth Activism and the Climate Crisis

From School Strikes to Global Climate Talks The latest episode of the Irish Global Solidarity in 100 Objects podcast features Beth Doherty, climate activist and

Mary Lawlor: Defending Human Rights Defenders

A Conversation with the UN Special Rapporteur for Human Rights Defenders The latest episode of the Irish Global Solidarity in 100 Objects podcast features Mary

Irish Women in Activism and Advocacy: In Awe of All Mná

Explore inspiring stories of Irish women in activism and advocacy who have fought for human rights, social justice, and equality at home and abroad

Call for resource submissions open – education resources during an era of climate promises, disinformation and pandemics

Submit or recommend resources to be included in the Ireland-wide audit of development education and global citizenship education resources.

Podcast: If Another World Is Possible, It Is Up to Us to Make It So

A Reflection on Palestinian Solidarity and Collective Action In this episode of the Irish Global Solidarity in 100 Objects podcast, Ciara Regan revisits her 2021

Podcast: Exploring Global Citizenship with a Ball of String

The Power of Simple Tools in Teaching Global Citizenship Sometimes, the most impactful lessons come from the simplest tools. In this episode of the Irish