On the 25th anniversary of the most progressive agenda to advance women’s rights across the world, Ciara Regan introduces the Beijing Platform for action, summarises progress to date and suggests 5 activities for classroom use.

‘Here is a story from my childhood. When I was in primary school in Nsukka, a university town in south-east Nigeria, my teacher said at the beginning of term that she would give the class a test and whoever got the highest score would be the class monitor. Class monitor was a big deal. If you were class monitor, you would write down the names of the noise-makers each day, which was heady enough power on its own, but my teacher would also give a cane to hold in your hand while you walked around and patrolled the class for noise-makers. Of course, you were not allowed to actually use the cane. But it was an exciting prospect for the nine-year old like me. I very much wanted to be a class monitor. And I got the highest score on the test.

Then, to my surprise, my teacher said the monitor had to be a boy. She had forgotten to make that clear earlier; she had assumed it was obvious. A boy had the second-highest score on the test. And he would be monitor.

What was even more interesting is that this boy was a sweet, gentle soul who had no interest in patrolling the class with a stick. While I was full of ambition to do so.

But I was female and he was male and he became the class monitor.

I have never forgotten that incident.

If we do something over and over again, it becomes normal. If we see the same thing over and over again, it becomes normal. If only boys are made the class monitor, then at some point we will all think, even if unconsciously, that the monitor has to be a boy. If we keep seeing only men at the head of corporations, it starts to seem ‘natural’ that only men should be the heads of corporations.’

Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, 2014

Beijing +25

In September 2020 it was twenty-five years since the Fourth World Conference on Women in Beijing set a path-breaking agenda for women’s rights. As a result of the two-week gathering with more than 30,000 activists, representatives from 189 nations unanimously adopted the Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action. This historic blueprint articulated a vision of equal rights, freedom and opportunities for women – everywhere, no matter what their circumstances – that continues to shape gender equality and women’s movements worldwide.

The Beijing Platform for Action imagined a world where every woman and girl can exercise her freedoms and choices, and realise her rights, such as to live free from violence, to go to school, to participate in decisions and to earn equal pay for work of equal value. As a defining framework for change, the Platform for Action made comprehensive commitments under 12 critical areas of concern.

A quarter century on, the UN Secretary-General, Antonio Guterres, calls for urgent action:

“With nations around the world searching for solutions to the complex challenges of our age, the leading way for all of us to rebuild more equal, inclusive, and resilient societies, is to accelerate the implementation of women’s rights – the Beijing Platform for Action. That vision has been only partly realized. We still live in a male-dominated world with a male-dominated culture, and this simply has to change”.

Twenty-five years later, no country has fully delivered on the commitments of the Beijing Platform for Action, nor is close to it. A major stock-taking UN Women report published earlier this year showed that progress towards gender equality is faltering and hard-won advances are being reversed. Women currently hold just one quarter of the seats at the tables of power across the board. Men are still 75 per cent of parliamentarians, hold 73 per cent of managerial positions, are 70 per cent of climate negotiators and almost all of the peacemakers.

The anniversary is a wake-up call and comes at a time when the impact of the gender equality gaps is undeniable. Research shows the COVID-19 pandemic is exacerbating pre-existing inequalities and threatening to halt or reverse the gains of decades of collective effort – with just released new data revealing that the pandemic will push 47 million more women and girls below the poverty line. We are also witnessing increased reports on violence against women throughout the world due to the lockdowns, and women losing their livelihoods faster because they are more exposed to hard-hit economic sectors.

While much works remains on fulfilling the promises of the Beijing Platform for Action, it continues to be a global framework and a powerful source of mobilization, civil society activism, guidance and inspiration 25 years later.

Why We Need to Return to it

The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) were hailed as a landmark achievement for women’s rights and gender equality. SDG 5 (Gender equality: achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls) includes targets such as ending discrimination against women, gender-based violence, participation of women at all levels of decision making and to give appropriate value to unpaid care and domestic work. These are critical starting points in the fight against inequality. However, they fall short of those made in the Beijing Platform for Action which required governments, the private sector, financial institutions, donors and civil society to advance 50 strategic objectives covering 12 critical areas of concern, which included poverty, education, health, violence, armed conflict, the economy, power and decision making, the environment, rights of women and girls.

By way of example, where the SDGs aim broadly for equal access to justice, the Beijing agreement specifically commits governments to ensuring access to free or low-cost legal services designed to reach women living in poverty.

Where the SDGs speak vaguely of promoting peaceful and inclusive societies, the Beijing agreement requires governments to reduce excessive military expenditure and control the availability of arms.

Where the SDGs include general targets on decent work and reducing income inequality, the Beijing agreement recognises the right of female workers to organise and states the key role of collective bargaining in eliminating wage inequality.

And where the SDGs require governments to reduce illicit financial flows, the Beijing agreement requires governments to analyse and adjust macroeconomic policies, including taxation and external debt policy, from a gender perspective ‘to promote a more equitable distribution of productive assets, wealth, opportunities, income and services.’

12 Critical Areas of Concern

- Women and Poverty

- Education and training of women

- Women and health

- Violence against women

- Women and armed conflict

- Women and the economy

- Women in power and decision making

- Institutional mechanisms

- Human rights of women

- Women and Media

- Women and the environment

- The Girl Child

How far have we come?

Women’s rights in review 25 years after Beijing

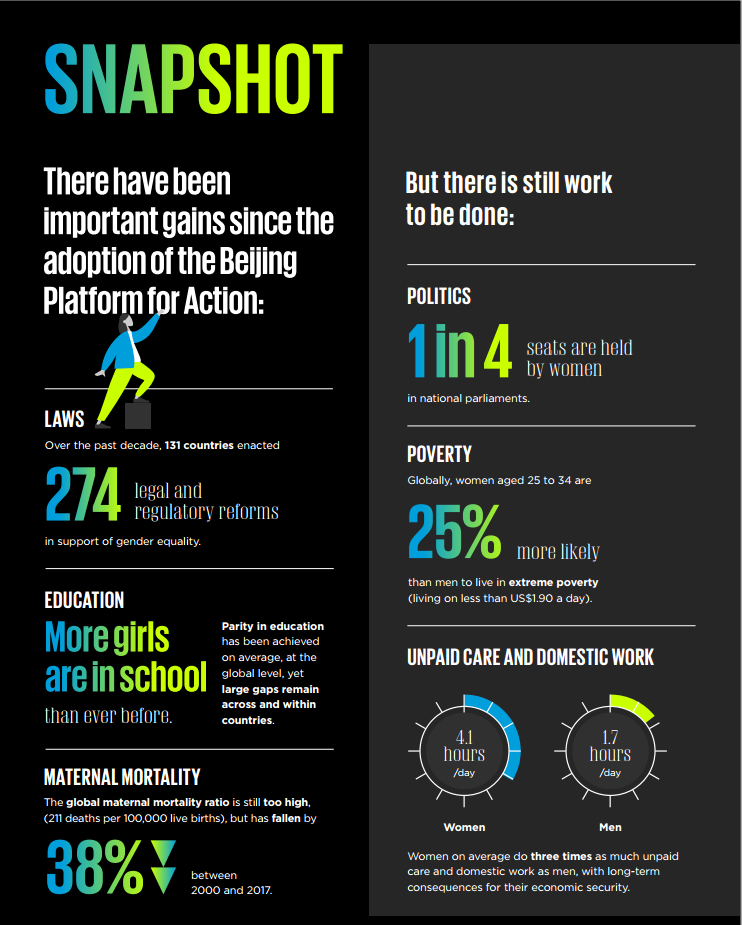

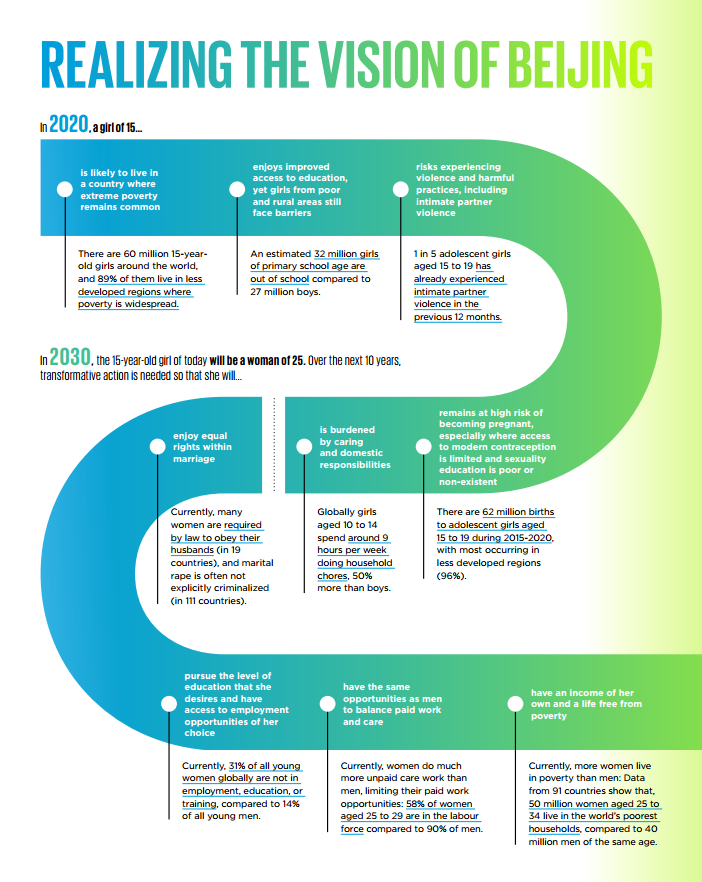

Today, a 15-year-old girl in the developing world has more opportunities than ever before. Compared to previous generations, she is much less likely to live in extreme poverty, and has a better chance of growing up healthy and nourished. Thanks to shifts in laws, policies and social norms that have changed the world around her, she is more likely to be able to finish primary school and less likely to marry young and become a mother before she is ready. With more role models to look up to in the political leadership of her nation, this young woman can aspire to great things.

YET, she will still be fighting against the odds because this progress, though important, has been incremental, uneven and insufficient. A billion people have escaped from extreme poverty since 1990, but poverty still has a female face. Although the number of out-of-school children at primary and lower secondary levels has nearly halved since 1995, 32 million girls of primary age are still out of school. The rate of child marriage has declined from one in four to one in five, but 650 million women alive in the world today were married before their 18th birthday. Politics is still an overwhelmingly male domain, with three quarters of parliamentary seats held by men.

This picture falls far short of the vision that was laid out in the Beijing Platform for Action a quarter of a century ago. It also bodes ill for reaching the Sustainable Development Goals a decade from now, progress on which critically depends on greater gender equality.

Realising the Vision of Beijing

Gains Made Since the Adoption of the Beijing Platform for Action

- Inclusive Economies and Decent Work (p6&7)

- Poverty Eradication and Well Being (p8&9)

- Leaving No Woman or Girl Behind (p10&11)

- Freedom from Violence, Stigma and Stereotypes (p12&13)

- Participation, Accountability and Institutions (p14&15)

- Peaceful and Inclusive Societies (p18&19)

- Climate Action and Environmental Sustainability (p20&21)

Feminist Voices

Activities

1. Only Equal is Enough

The above title (‘Only equal is enough‘) is from Phumzile Mlambo-Ngcuka, Under-Secretary- General and UN Women Executive Director.

- Use this quote to begin a discussion about what that means. What does ‘equal’ mean in this context?

‘Under-representation of women in power and decision-making is still the norm. We are impatient for that to change… Only half is an equal share, and only equal is enough’

Phumzile Mlambo-Ngcuka, Under-Secretary- General and UN Women Executive Director

2. Exploring the power of different voices

- Use Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie‘s story from her childhood (above) to stimulate discussion and debate: Why does the group think this story is relevant to women’s rights? Does the group agree with the overall message of the story? Do incidents like this still happen now? Has anyone in the group had a similar experience?

- Adichie states ‘If we keep seeing only men at the head of corporations, it starts to seem ‘natural’ that only men should be the heads of corporations’. What is the group’s reaction to this quote?

- Using the ‘Feminist Voices’ image above; Who would the group add to their list of important voices here?

3. Examining 12 critical areas of concern

- Ask the group to rank the 12 Critical Areas of Concern in order of importance. This can be done in groups of 2-3, before having a whole group discussion to see if there is an overall consensus.

4. Posters and poetry

- Download the poster series on the right, created by a group of students from Loreto, Bray.

- What are the group’s reactions to the four posters? Which one do they like best? Why?

- How many of the 12 Critical Areas of Concern are linked to these posters?

- ‘And Still I Rise’ is a line from a poem by Maya Angelou of the same name. Watch her recite her poem. Discuss.

- In pairs, or individually, design your own posters to create awareness around/educate on these areas of concern and share them with us to be included for others to learn from.

5. Write a review

- In groups of 2-3, use the double page spreads from the Women in Review 25 Years after Beijing report from UN Women to do a research project/write a newspaper article/presentation for your peers on an issue the group feels is of critical importance.

- Share your work with us to potentially get your work published

- Tagged as Beijing Platform for Action, human rights, Women’s Rights

For more on developmenteducation.ie

Beth Doherty: Youth Activism and the Climate Crisis

From School Strikes to Global Climate Talks The latest episode of the Irish Global Solidarity in 100 Objects podcast features Beth Doherty, climate activist and

Mary Lawlor: Defending Human Rights Defenders

A Conversation with the UN Special Rapporteur for Human Rights Defenders The latest episode of the Irish Global Solidarity in 100 Objects podcast features Mary

Irish Women in Activism and Advocacy: In Awe of All Mná

Explore inspiring stories of Irish women in activism and advocacy who have fought for human rights, social justice, and equality at home and abroad

Call for resource submissions open – education resources during an era of climate promises, disinformation and pandemics

Submit or recommend resources to be included in the Ireland-wide audit of development education and global citizenship education resources.

Podcast: If Another World Is Possible, It Is Up to Us to Make It So

A Reflection on Palestinian Solidarity and Collective Action In this episode of the Irish Global Solidarity in 100 Objects podcast, Ciara Regan revisits her 2021

Podcast: Exploring Global Citizenship with a Ball of String

The Power of Simple Tools in Teaching Global Citizenship Sometimes, the most impactful lessons come from the simplest tools. In this episode of the Irish