Indian scholar, economist and philosopher Amartya Sen sees development as a gradual process of expanding freedoms equally for all people. Gender equality, from this perspective, is a core objective of development in itself implying that:

just as development means less income poverty or better access to justice, it should also mean fewer gaps in well-being between males and females’

Recent additions

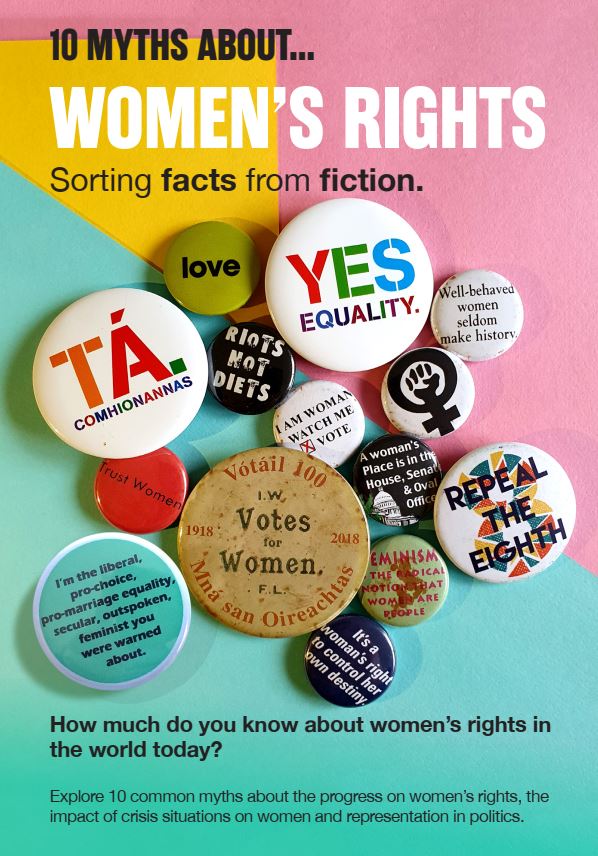

10 Myths About Women’s Rights – the booklet

Women’s rights quiz – take the test

‘Only Equal is Enough’ – Exploring the Beijing Platform for Action in the classroom

Yet, today’s development realities beg the question as to whether we are achieving this objective sufficiently and in a reasonable timeframe. Although there has been considerable and important progress in terms of women’s well-being (in rights, education, health and access to jobs etc), what of their ‘ill-being’? It is still the case that NO country treats it women the same as its men.

‘Things have changed for the better, but not for all women and not in all domains of gender equality. Progress has been slow and limited for some women in very poor countries, for those who are poor, even amid greater wealth, and for those who face other forms of exclusion because of their caste, disability, location, ethnicity, or sexual orientation. Whether comparisons between men and women in the same country, or absolute comparisons of women across countries, the progress in some domains is tempered by the sobering realities that many women face in others’.

– World Development Report 2012

In this module we have chosen to focus specifically on women per se, and not gender in general for a number of reasons and to highlight a number of important issues.

- The role of women in developing countries, as explored throughout this module, has been recognised as the single most important factor when it comes to bringing about and sustaining long term social change. Women are farmers and food providers (contributing to agricultural output, general environmental maintenance and food security); they are business people and traders (40% of the world’s labour force are women, not including informal work in the home, on the land, in the market place etc); they are heads of households (most of whom are likely to also have a full time job, as well as caring for children, elderly or sick relatives); they are mothers, carers and support workers (more often than not, in developing countries, this is voluntary); and they are community leaders, activists and role models (stemming from their roles in society as mothers, carers and support workers).

- Development affects men and women differently, often with a more negative impact on women. This can undermine women’s role, status and position within society and therefore perpetuates their inequality.

- Women’s equality is vital to sustainable development and the realisation of human rights for all. Equality for women is vital economically, politically, socially, culturally and environmentally – it is also crucially a matter of basic human rights.

3 entry points – Politics, Maternal Health & Poverty

Women & Politics

Azza Badra was one of thousands of women in Tunisia who competed for a seat in 2011 national elections, the first since the country’s pro-democracy shift in January 2011 and since its independence in 1956. Badra, a mother of two, ran as a Green Tunisia Party candidate in the capital Tunis for one of 217 seats in the Constituent Assembly.

‘It’s simple statistics. We’re the majority,’ said Badra, whose campaign prop was a mock Tunisian ID card featuring the number 51, the percentage of women in the country’s population. Badra was among more than 4,000 women running in an election for their first time following May 2011 legislation requiring that party candidate lists alternate between women and men.

In spite of the lists, women’s actual representation in the new assembly will not reflect their proportion of the national population. Women headed only seven percent of the more than 1,500 candidate lists.

‘The number of women will be less than Tunisians deserve,’ said Bushra Balhaj Hmeida, a veteran lawyer and human rights activist, ranked top of the Al Takkatul Party candidate list in Zaghwan precinct.

‘While I believe men and women in politics are the same, my conviction is that women can improve politics and restore Tunisians’ trust in the political process. Women can make politics more human.’

Source: UNDP

Women & Maternal Health

‘In the market town of Senafe, in southern Eritrea, Fethawi Berhane had undergone three days of painful labour and complications during childbirth that resulted in the death of her baby, despite the best efforts of a traditional birth attendant. Fethawi herself was lucky to have survived, given the unhygenic and poorly equipped medical conditions in which she had to give birth. Fethawi’s case is not unique in Eritrea (or in many other parts of the poor world), which once had the highest maternal mortality rates in the world (about 1400 deaths per 100,000 births). The main contributor to this rate was the high incidence of obstructed labour.

The rural nature of Eritrea, with its poor communication and transportation infrastructure, particularly in outlying areas, has caused 80% of deliveries to take place without a physician or trained midwife present.

Today, however, Eritrea is one of the four African countries said to be on track to achieve Millennium Development Goal 5 on Maternal Health, which calls for countries to reduce their maternal mortality rate by three quarters by 2015. For Eritrea, this will mean attaining a rate of less than 350 deaths per 100,000 births. This is as a result of a programme of action involving the Eritrean Government, international bodies such as UNICEF and UNDP and crucially, local communities. As a result, each community in Eritrea now has fully-trained maternal care givers and expectant mothers living far from medical centres do not have to risk their lives travelling long distances while in labour. Instead, trained birth attendants visit them in their homes before and after delivery to provide medical assistance and ensure that both mother and baby are in good health. But many communities and individual women still need to access the programme in the years ahead.

Source: UNDP

Women & Poverty

The Working Women’s Forum in India has mobilised 280,000 women throughout India in a range of programmes from credit banks to training workshops. ‘Most of the women,’ explains Nandini Azad ‘are poor – really poor. Around 89% work in the informal economy – as street vendors, landless labourers, or beedi (local cigarette) makers. But they try to use the economic situation as an opportunity rather than viewing it as a disaster’. Lakshmiamma, a lace-maker in Narsapur, gave a talk to the other women recently. She gave them some sound advice:

‘I do not know enough to give you advice but I can give you a message that my President gave me when we started to organize the women lace-makers. The rich will always help the rich. The poor will therefore have to help the poor. Reach out to the poorest wherever they are and help them to help themselves… Then you will succeed…’

Inevitably, there is also resentment from men – Christine Bradley, who has campaigned against domestic violence in Papua New Guinea, puts it:

‘Women’s development threatens male authority. Although this is seldom openly acknowledged… the position of women exists not in a vacuum but in relation to the position of men. Eliminating discrimination against women is another way of saying eliminating discrimination that favours men. Not surprisingly, men don’t like this. And where men hold most of the power, what men think has serious consequences for women.’

Source: New Internationalist

Fast Facts on Women

- Despite progress in recent years, women and girls continue to account for 6 out of 10 of the world’s poorest.

- Two thirds of the world’s illiterate population are women.

- Women perform 66% of the world’s work, produce 50% of the world’s food but earn only 10% of the income and own only 1% of the property.

- Only 19% of the world’s parliamentarians are women.

- One third of all women are subjected to violence whether in conflict situations, or in the home.

- Despite the disproportionate impact of conflict on women, fewer than 3% of signatories to peace agreements are women. Out of 585 peace agreements signed worldwide since 1990, only 16% contained any reference to women and only 7% mentioned gender equality or women’s human rights.

- Of the 72 million children worldwide who are not in school, 57% are girls – despite the fact that if a country educates its girls, its mortality rates usually fall, fertility rates decline and health and education prospects improve overall (World Bank).

- On average, women earn 20% less than men worldwide – although, this figure varies from country to country.

- In some developing countries, one in 65 women risks death during pregnancy or childbirth.

- Approximately 100 to 140 million girls and women in the world have experienced female genital cutting/mutilation. In Africa, more than 3 million girls continue to be at risk of FGM/C every year.

- Of the 800,000 people trafficked worldwide every year, 80% are women or girls. 79% of which are trafficked for sexual exploitation.

- 186 countries have now signed up to the UN Convention for the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW).

- Mortality for adult women has fallen by 23% since the 1990s (UNDP report 2010) What has taken the United States 40 years to achieve in increasing girl’s enrolment, has taken Morocco just a decade.

- Two thirds of all countries have reached gender parity in primary education enrolments.

- At 71%, Denmark has the highest rate of female participation in the workforce in the EU.

- The number of women in Ireland being supported by Sonas, the Irish charity that provides housing support to women and children affected by domestic violence, has increased by 163% since 2009.

- In 1965 only 5% of American men cooked for their families. Today, one third of cooking in US households is done by men.

- If the average distance to the moon is 394,400km, South African women together walk the equivalent of a trip to the moon and back 16 times a day to supply their households with water.

- A 2003 report in America put the cost of domestic violence at US$5.8bn. Medical care accounted for US$4.1bn, while productivity loses added a further US$1.8bn.

- A study by the London School of Economics found that boys are more likely to receive preferential treatment in rescue efforts following natural disasters, and that girls suffer more from shortages of food and lack of privacy and safety. In addition, in many countries, girls are discouraged from learning survival skills, such as swimming or climbing.

- The study of 141 countries by the London School of Economics also found that gender differences in loss of life due to natural disasters are directly linked to women’s economic and social rights. The study found that in societies where women and men enjoy equal rights, losses in life due to natural disaster were more gender balanced.

- In Kenya it has been found that drought has affected school attendance, with girls being more likely to be withdrawn from school than boys.

- Drought and food shortages have led to higher rates of early marriage for girls – or famine marriages, as they have been called. In Uganda, for example daughters are often exchanged like commodities by their families.

- Women reinvest almost 90% of their income back into their families and communities, compared to men who reinvest only 30% to 40% of their incomes (Borges, 2007).

Sources: UNSTATS, UN Fast Facts sheet, Facing the Future, UN Women

Further Information

Afghanistan has been named as the world’s most dangerous country in which to be born a woman, followed by the Democratic Republic of Congo, Pakistan, India and Somalia. See British newspaper, The Guardian’s interactive map* for more information, facts and figures.

* Please note: there are some images with graphic content in the interactive map.

‘It is about having half of humanity participate.

The progress of women means…the progress of the world’.

U. Joy Ogwu, Ambassador of Nigeria to the UN, President, UN Women Executive Board 2011

It has been long argued that empowering women can benefit human development and society overall not only in developing countries but worldwide. In most parts of the world, women fulfil many traditional roles such as mothers and carers, support workers and heads of household but, in more recent decades have come to occupy a far broader range of roles and the work that previously was not recognised or accounted for has begun to get recognition. It is now broadly agreed that significant economic, social and political progress can be achieved if countries invest appropriately in their women through access to education, greater decision-making power and more extended access to resources of all types. For example, investing in women can lead to:

- Poverty reduction: As mentioned previously, women account for 6 out of the 10 poorest people in the world. Better access to resources for women can help to increase household incomes. The World Bank argues that by giving women more access to human capital, credit, land and fertiliser, total agricultural production could increase by between 6-20% in sub-Saharan Africa because of the central role of women in agriculture.

- Improved Education and health: There are strong links between women’s education and health. According to EarthTrends, from 1975 to 1995, gains in women’s education in 63 different countries contributed significantly to a reduction in malnutrition. Better education for women also has a direct (positive) impact on HIV infection rates.

Source: EarthTrends

The Education for All report 2011 outlines the impact of education on the health of women and children:

- A 10% increase in girls’ secondary school enrolment in low income countries will save approximately 350,000 children’s lives and reduce maternal mortality by 15,000 deaths every year

- Girls’ education is often the single most powerful factor affecting health outcomes: infant and maternal mortality, seeking safer birth options, averting risky teenage births, likelihood of having smaller and healthier families

- HIV and AIDS infection rates drop by 50% among children who complete their primary education

- If all children received a primary education, 7 million HIV cases worldwide could be prevented each year

- An estimated 1.8 million children’s lives in sub-Saharan Africa could be saved this year if their mothers had a secondary education

- Every additional year of schooling reduces the number of children a woman will have by 10%

- Investing in girls education could boost sub-Saharan Africa’s agricultural output by 25%

- Girls’ income potential increases by 15% with each additional year of primary education Increasing the number of women with secondary education by 1% can increase annual per capita economic growth by 0.3%

The Role of Women

The role of women in development is vital. However, it has changed somewhat over the years:

Women are farmers and food providers – In some parts of the world, 80% of basic food is produced by women. In doing this, women contribute to national agricultural output, general environmental maintenance and, most importantly, family food security. They achieve this despite the unequal access to land, machinery, fertilisers etc. It has been claimed that if men and women had equal access to these resources, there would be substantial gains in agricultural output for both men and women, their families and their communities (ifpri.org).

Women are business people and traders – Up to 40% of the world’s labour force are women and this does not include the informal work carried out by women. More often than not, workers in factories, in the home, on the land and in the market place are women. Despite this fact, the majority of these women remain dependent on men due to lack of access to necessary resources such as capital or credit, household resources and due also to patriarchal practices and traditions (link to definition in HIV and AIDS glossary) including those that relate to the economic position of women.

Women are heads of households – In both developed and developing countries there has been an increase in female-headed households due to male migration, high death rates due to conflict or illness and abandonment or separation. Although female heads of households are much more likely to work than married women, they are ultimately more vulnerable to poverty, as their income would generally be lower than men’s. Female heads of households are likely to have a full time job, as well as care for and feed their children and any elderly or sick relatives and maintain their home also.

Women are mothers, carers and support workers – In small rural communities in developing countries, more often than not, it is women who volunteer to be carers or support workers for local hospitals, charity organisations, community projects etc. See, for example, Florence Hagila (Note for Dylan:link to biography below) in our ‘Women in Development’ section below. Some 60%, or more, of female workers in developing countries are in informal employment (outside of agriculture). In sub-Saharan Africa alone, 84% of female, non-agricultural workers are informally employed.

Source: Women in Informal Employment Globalizing and Organizing – WIEGO.

Women are community leaders, activists and role models – This stems from women’s role as mothers, carers and support workers. People within the community these women work in would look to them for help or guidance. Despite the high number of female community leaders and activists, women are still under-represented at higher levels with only 19% of women in parliamentary positions in the world.

Where Women fit in human development terms: WID, WAD & GAD

They live as a small community in this place. Since they usually come from the same village, they share and practice common custom as these women prepare the food.

Over the decades, questions have been raised as to whether women’s development is a separate issue to that of development in general. Research and on the ground experience claims that, in general, women have not benefited from development processes, programmes and projects to the same extent as men had. Previously, women were very often not included in the planning or implementation of development programmes and projects.

Development can sometimes even undermine the role, status and position of women in society. Development affects women and men differently, often with a more negative impact on women. Women’s health, education, economic opportunity and human rights are fundamental in achieving successful economic growth and stable societies. These debates and ideas have lead to the emergence of three distinct models with regards to women and their relationship with development: WID, WAD and GAD.

- WID: The ‘Women in Development’ approach emerged in the early 1970s when it became apparent women were not benefitting from development due to their exclusion from development programmes. WID made demands for women’s inclusion in development; however, it did not call for fundamental changes in the overall social structure or economic system in which women were to be included. WID focused on women exclusively and almost outside of the mainstream of development.

- WAD: The ‘Women AND Development’ approach of the late 1970s focused on the interaction between women and development, rather than purely on strategies to integrate women into development. It appeared that neither men nor women were benefitting from development due to class inequalities and the unequal distribution of wealth. WAD focused strongly on class (including men), in practical project design and implementation, it tends, like WID, to group women irrespective of other considerations such as class divisions.

- GAD: The ‘Gender and Development’ approach emerged in the 1980s from a coming together of many feminist ideas and lessons learned from the limitations of WID and WAD. It focuses on the social or gender relations (i.e. division of labour) between men and women in society and emphasises the productive and reproductive roles of women. It goes beyond seeing development as mainly economic well-being, but also the social and mental well-being of the individual.

Until the 1990s, a country’s progress was measured by its Gross National Product (GNP) or Gross Domestic Product (GDP), which reflected the performance of the country and it”s per capita income, focusing on income distribution within economies. These indicators, however, did not go far enough in that they did not show the well-being (or ill-being) of people living within these economies (i.e., health, education, water and sanitation needs etc). Equally, an economically poor country may actually provide quite well for its people in terms of human development.

Human Development Index (HDI)

The HDI was constructed by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) and has 3 main focus indicators:

- Health (including life expectancy at birth)

- Education (including literacy levels, average number of years in school and expected number of years in school)

- Living standards (Gross National Income per capita)

These three indicators are used to form the HDI of a country and can be used to compare poverty, deprivation and development in different parts of the world. Examples of a High HDI include countries such as Norway, Ireland and Japan. Low HDI countries include Ethiopia, Zambia and Somalia (according to the 2010 rankings).

In 1995, the UNDP created the Gender-related Development Index (GDI) and the Gender Empowerment Measure (GEM) in order to adjust the Human Development Index to include gender equality measures. The differences between men and women in relation to the different dimensions of human poverty are now measured through using the GDI and GEM.

Gender-Related Development Index (GDI)

GDI is an indicator of gender inequalities in the basic human development indicators. It measures in the same way as the HDI, but takes note of inequality in achievements between men and women. The greater the gender gap in basic capabilities, the lower a country”s GDI is in comparison with its HDI.

Examples of countries with:

- High GDI rankings include: Iceland, Norway, Hong Kong, Barbados and Brazil.

- Middle GDI ranking: Columbia, China, Algeria, Sudan and Uganda

- Low GDI ranking: Eritrea, Zambia, Mali, Niger and Sierra Leone

Gender Empowerment Measure (GEM)

GEM measures gender inequality in economic and political participation and decision making.

While GDI focuses on expansion of capabilities, the GEM is concerned with the use of those capabilities to take advantage of the opportunities in life.

Examples of Countries with:

- High GEM ranking: Sweden, New Zealand, Ireland and Israel.

- Middle GEM ranking: Malta, Romania, Brazil and Nepal.

- Low GEM ranking: Sri Lanka, Turkey, Bangladesh and Yemen.

Source: UNDP

Gender Inequality Index (GII)

Introduced in 2010 by the UNDP Human Development Report, the Gender Inequality Index (GII) is described as “a composite measure reflecting inequality in achievements between women and men in three dimensions: reproductive health, empowerment and the labour market”. It ranks from 0 – 1, zero being where women and men fare equally.

- Health is measured by two indicators: maternal mortality ratio and the adolescent fertility rate.

- The empowerment dimension is measured by two indicators also: the share of parliamentary seats held by each sex and by secondary and higher education attainment levels.

- The labour dimension is measured by women”s participation in the workforce.

Overall, the GII is designed to reveal the extent to which national achievements in these aspects of human development are eroded by gender inequality.

For more information on the GII and why it has replaced the Gender Development Index and Gender Empowerment Measure, see theUNDP”s FAQ”s on the subject.

“Women have made unprecedented gains in rights, in education and health, and in access to jobs and livelihoods. More countries than ever guarantee women and men equal rights under the law in such areas as property ownership, inheritance and marriage. In all, 136 countries now have explicit guarantees for the equality of all citizens and the non-discrimination between men and women in their constitution”

Women – Land, Wealth & Poverty in Africa

Despite the fact that African women produce almost three-quarters of the continent”s food, they are still among the poorest of the poor. The majority of workers in the home, in the fields or in the markets are routinely women. Despite this fact, these women are dependent on men due to lack of access to capital or credit or control over household resources and due also to patriarchal practices and traditions including those that relate to the economic position of women. These practices and traditions extend into the ownership of land or property, in many cases women are restricted in owning or inheriting land or wealth. Lacking power or control over household or communal resources makes many women subservient to men and relatively powerless in negotiating decisions, including in the realm of sexual relations (for example, when and whom to have sex with and decisions over their own bodies such as the use of contraception etc).

Access to resources, such as land, credit and other productive resources by women is characterised by their lack of rights and lack of security in terms of land ownership. Most people in Africa live in community-based societies, where customary law rules. Traditionally in customary law, land is passed down through the males in the family and therefore, women only gain access to land through their male relatives. They obtain their use of the land through their roles as wives, daughters or sisters. When a woman marries under customary law, she will then be a part of her husband”s family or tribe and therefore any property will be passed along through the males in the family. In some countries, inheritance laws and practices dispossess widows of their marital property. If a relationship ends between a woman and her husband, there is a good chance that the woman will lose her home, land, livestock, household goods, money and sometimes even her children. These customary laws and practices ensure than women”s position in the home and community remains subordinate by perpetuating their dependence on men. The situation is further complicated by the fact that there are dual legal systems – customary and statutory law. Legally, women should be able to inherit land, but this is not always the case as the legislation is not always enforced, or women have no knowledge of their rights.

More recently, the situation is changing and women are beginning to inherit land under statutory law, or through “civil” court systems, instead of the “traditional” or “customary” court. In a large number of places, however, this is still ignored. Flora from Ijuhanyondo in Tanzania sums up this point:

“Yes, women can inherit property. In fact, in the will, the father is supposed to give each son and daughter something, and nowadays the law is strict, equally. But still, men give to their sons and argue that women have the property of where they are married”.

Defining Gender in the 21st Century, World Bank 2011

The Feminisation of Poverty

The “feminisation of poverty” originally comes from debates in the USA in the 1970s about single mothers and the welfare system. It has been linked to an increase in the proportion of female-headed households and to the rise in women working in low paid jobs in the informal sector, especially during the 1980s economic crisis and structural adjustment policies in sub-Saharan Africa. It wasn”t until the 1990″s that it became a more frequently used term within development. The “feminisation of poverty” is used to mean three distinct things:

- That women have a higher incidence of poverty than men;

- That their poverty is more severe than that of men;

- That there is a trend towards a greater poverty among women, particularly associated with rising rates of female headed households.

Other characterisations include

- Women face more barriers to lifting themselves out of poverty

- Female-headed households are considered to be “the poorest of the poor”

- Women are prone to suffering more persistent or longer term poverty than men.

Worldwide, women earn 20% less than what men earn, on average. As outlined in previous sections, women living in poverty are frequently denied access to important resources such as land, credit and inheritance and are thus caught in a cycle of poverty – they lack the resources they need to change their situation, or lift themselves out of poverty:

- 70% of the world”s poor are women, living on less than US$1.25 per day

- Six out of ten of the world”s poorest people are women who, as primary caretakers and producers of food in the developing world, shoulder the burden of tilling the land, carrying water and cooking for their families.

Source: UNWomen

Violence Against Women

One third of all women are subjected to violence whether in conflict situations, or in the home. This violence perpetuates the inequalities between men and women and jeopardises women”s dignity, integrity and freedom. It violates their human rights. It is reinforced by the social taboo that surrounds it – by the fact that the majority of women who suffer from this violence, suffer in silence. Violence against women has been described as “the most pervasive, yet least recognised human rights abuse in the world” – UNFPA. It can severely damage women”s emotional and physical well-being, including their reproductive health, and in some cases, it can even lead to death.

Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting

One area of violence against women and girls is the reality of Female Genital Mutilation or Cutting (FGM/C), which is “the partial or total removal of the female external genitalia or other injury to the female genital organs for cultural or other therapeutic reasons”. It has been estimated that approximately 100 to 140 million girls and women in the world have experienced female genital cutting/mutilation. More than 3 million girls are at risk of the procedure every year in Africa alone. The procedure is generally carried out on girls between the ages of 4 and 14. It has been known to have been performed on infants, women who are about to be married and in some cases women who have just given birth. It is usually performed by a traditional midwife or barber, most often without anaesthetic, using scissors, razor blades or broken glass. It is a hugely traumatic experience. More often than not, FGM/C leads to ulceration of the genitals, blood poisoning, infertility, obstructed labour, haemorrhaging and sometimes even death.

FGM/C subjects women and girls to life-threatening risks without any medical necessity – or permission from the woman or girl in question. It is a fundamental violation of their human rights depriving the individual of their freedom from degrading and inhumane treatment. It is used to control women”s sexuality, denying them the full enjoyment of their rights and freedoms.

Some Reasons for perpetuating the practice of FGM/C

The belief that FGM/C is necessary is rooted in certain cultural norms and traditional practices that are claimed to prepare girls for adulthood and marriage. It is seen to be part of a process to make girls “clean”, well behaved, responsible, beautiful and mature adults. It is believed to discourage frivolous behaviour in order to preserve morality and virginity. In more severe cases of FGM/C (where a seal is created over the vaginal opening using the surrounding skin), there is a physical barrier to sexual intercourse – thus ensuring the woman”s self-control. In many countries where FGM/C is practiced, it is seen as being part of a cultural identity, a coming of age. It is so widely accepted that families have their daughters cut, fully aware of the long term effects it can have on her – and that it may even kill her. From this perspective, not having their daughter cut would bring more harm to her and the family in terms of their social status.

For more information on FGM/C, see our blog post, which include links to stories from women such as Waris Dirie.

Source: UNFPA

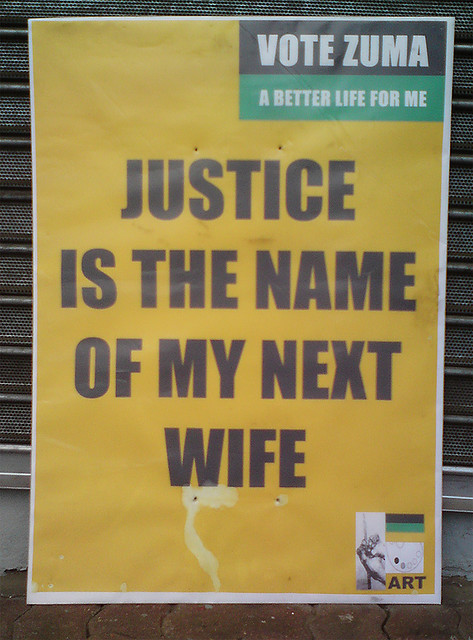

Women & Politics (including the role of women in politics and the right to vote)

Women are considerably under-represented in most of the world”s parliaments. The only exception is Rwanda that has a representation of 56.3% of women in their parliament* – although what does this representation mean in terms of actual power. On average, across every country”s parliament, women occupy only 18.4% of parliamentary seats. Although this is a very low figure, it is a vast improvement from even 15 years ago when it was only 10%. Contrary to popular perceptions, women are often as interested in politics as men are. For example, in Mexico, women make up 52% of party membership. In Paraguay, women”s party membership is as high as 46%. However, women are constantly under-represented in terms of leadership positions within political parties.

*It is important to note the uniqueness of the parliament in Rwanda as a result of its history. In 1994, extremists in government from the country”s largest ethnic group, the Hutu”s, initiated their plan to exterminate the Tutsi minority in Rwanda. What followed was the slaughtering of almost one million Tutsis (including Hutus opposed to the extermination) and the mutilation and rape of thousands more.

Constance Mukayuhi Rwaka – a Member of Parliament and economist – remembers women throughout Rwanda, joining forces, both formally and informally, to help those who were widowed or orphaned during the killing. “After 1994, Rwanda was in a very peculiar situation. Women had really been mobilised across the country”.

Athanasie Gahondogo, the Executive Secretary of the Forum for Rwandan Women Parliamentarians (who”s aim is to bring together women from Rwanda”s eight political parties to improve their status and heighten their profile) agreed – “The genocide has a lot to do with it in that women gained a very high profile afterwards”.

The strong showing for women candidates at the polls was also due, in part, to a UNDP initiative, with US$1.5 million in funding from the Netherlands. This funding was used to train women in decision-making positions, strengthen women”s civil society organisations and establish governmental units to look after the concerns of women.

For more information, see this report from the UNDP Newsroom

Representation of Women in Parliament

Source: 5:50:500

Current Female Heads of State around the world:

- President of Finland: Tarja Halonen (2000-present)

- Federal Chancellor of Germany: Angela Merkel (2005-present)

- President of Liberia: Ellen Johnson-Sirleaf (2006-present)

- President of India: Pratibha Patil (2007-present)

- President of Argentina: Christina E. Fern?ndez de Kirchner (2007-present)

- Prime Minister of Bangladesh: Sheikh Hasina Wajed (2009-present)

- Prime Minister of Croatia: Jadranka Kosor (2009-present)

- President of Kyrgyzstan: Roza Otunbayeva (2010-present)

- President of Brazil: Dilma Vana Linhares Rousseff (2011-present)

- Prime Minister of Australia: Julia Gillard (2010-present)

The role of women in politics?

- Women have as much a right as men to be in positions of power in politics. The ability to perform these roles is not gender specific.

- Increasing the number of women involved in politics is not just about democratic justice or equality, it is also about ensuring better accountability for women.

- Women have different priorities to men, such as childcare provisions and social protection, which is then reflected when they are elected into office.

- More women are encouraged to engage with politics and voting if there is more female political representation.

- A democratic government must represent and be accountable to the people it serves. When women are in positions of power, it creates a positive accountability cycle whereby issues thought to be only of interest to women are re-evaluated as issues affecting society as a whole. For example, domestic violence is now considered a societal problem rather than just a women”s rights issue.

The Right to Vote

Universal suffrage:

Universal suffrage is the extension of the right to vote to every adult citizen. Almost 100 years ago, not one country had universal suffrage, with the most commonly excluded groups being women and ethnic minorities. Originally, it was only the privileged few who had the right to vote, rather than all citizens. These privileged few were from aristocratic backgrounds or were land owners which therefore meant that the majority of people were denied the right to vote (or were “disenfranchised”).

Historically, women weren”t always necessarily denied the right to vote. In medieval France, for example, all heads of households were allowed to vote, regardless of gender. In a number of cases, women had the right to vote prior to universal suffrage. Therefore, some women (female aristocracy) were allowed to vote when others were not.

Female Suffrage:

Female suffrage was very slow to be introduced, and when it was introduced, it did not necessarily mean that it was permanent or unconditional. For example, in the 1700s in Corsica, women had the right to vote. That is until France took over in 1755 and repealed the Corsican constitution which had granted universal female suffrage.

In 1893, New Zealand became the first nation to grant women unrestricted suffrage. In 1905, Finland became not only the first European country to grant universal suffrage, but it also became the first country in the world to elect female members of parliament with 19 women elected.

For an interactive timeline of the development of women”s right to vote see the Guardian.

There are still a number of countries today who continue to deny women the right to vote, or they may have the right, but certain conditions must be met first:

- Brunei: Women cannot vote nor stand for election.

- Lebanon: Women must be able to prove they have a primary education in order to gain the right to vote. This restriction does not exist for men.

- United Arab Emirates: Suffrage is extremely limited. In the 2006 elections, only 1% of the population was allowed to vote.

- Vatican: Only members of the Papal Conclaves are allowed to vote, who are all Cardinals and, hence, men.

The Suffragettes:

The Suffragettes were radical female campaigners in the early part of the 20th century who fought for female suffrage – sometimes violently. They emerged from within the women”s movement campaigning for constitutional change, but with the belief that direction action, and sometimes violence, was needed to bring about change. The Women”s Social and Political Union (WSPU) was formed with Emmeline Pankhurst as their leader. It was this group that was first labelled “the Suffragettes”.

As the struggle intensified, so did the Suffragettes” forms of direct action. Beginning with loudly protesting at public meetings they progressed to hunger strikes while in prison, chaining themselves to railings, burning Churches and even bombing politicians” houses.

The Suffragettes” campaign showed no signs of abating, but in 1914 World War I broke out. Following the instructions of their leader Emmeline Pankhurst, the Suffragettes stopped their renegade campaigning and supported the government in its war effort. As the war drew to a close, the British Parliament passed the 1918 Representation of the People Act, which granted women over the age of 30 the right to vote. Universal female suffrage came a decade later, in 1928. Ironically, the war probably helped further the Suffragettes” cause. By calling off their violent struggle and dedicating themselves to working in factories and fields, the Suffragettes proved indispensible to the war effort and made the British government more willing to move towards universal female suffrage. It also did away with the sexist belief that women were weak, sickly things unable to do factory work or other hard labour.

Further Information

For more information see The Women”s Library at the London Met. It describes itself as “a cultural centre housing the most extensive collection of women”s history in the UK”. While many of their collections are only available in hard copy, their website hosts a variety of pamphlets, periodicals and videos, as well as electronic resources.

The British Pathé website has documentaries on women”s emancipation, as well as great speeches, original footage, stills and audio from the campaigns for emancipation

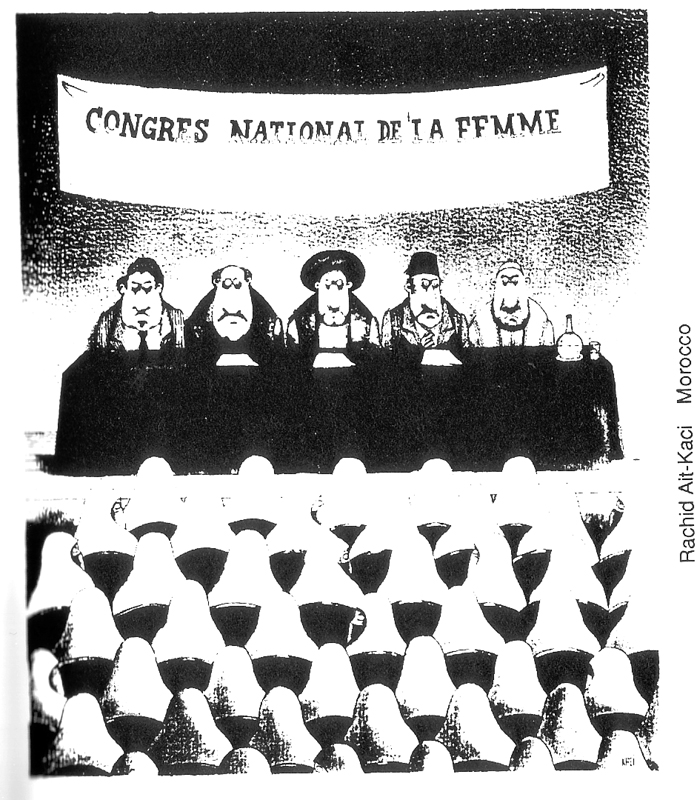

Women in the Arab World

It is undeniable that women are considerably under-represented in politics in the Arab world. There are a number of reasons for this, from systemic to religious to cultural. While highlighting the obstacles Arab women face while trying to gain political empowerment, the UNDP”s Arab Human Development Report claims that ‘in all cases… real decisions in the Arab world are, at all levels, in the hands of men”. The patriarchal political systems currently in place and cultural and societal barriers to women”s entry into politics or senior decision making positions are the most difficult to overcome in terms of women gaining any sort of political empowerment.

Since the 1990s, appointing women to ministerial positions in Arab governments has been a general rule and has been increasing steadily since. However, their participation in government has been tokenistic with only one or two female ministers, social (women are usually appointed to ministries of social affairs, or other ministries related to women) or conditional (the number of female ministers changes with numerous changes of government). Although there is progress, it remains extremely limited.

‘Political forces on the Arab scene do not oppose the rise of Arab women or their political and social participation; all accept the legal and political equality of women. The problem lies in these forces” implementation of their principles in party and political life.”

Arab Human Development Report 2005

Below are the profiles of four individual women who have devoted their lives to supporting the development of other women throughout the world. The women originate from Kenya, Ireland, Zambia and Bangladesh.

Wangari, Mary, Florence and Taslima: Profiles of four women’s rights activists

Wangari Maathai

Wangari Muta Maathai was born in Nyeri, Kenya in 1940. The first woman in East and Central Africa to earn a doctoral degree, Wangari obtained a degree in Biological Sciences from Mount St. Scholastica College in Atchison, Kansas in 1964 and subsequently earned her Master of Science degree from the University of Pittsburgh two years later. Maathai pursued doctoral studies in Germany and the University of Nairobi, obtaining a Ph.D. in 1971 from the University of Nairobi where she also taught veterinary anatomy. She became chair of the Department of Veterinary Anatomy and an associate professor in 1976 and 1977 respectively. In both cases, she was the first woman to attain those positions in the region.

Wangari Muta Maathai was born in Nyeri, Kenya in 1940. The first woman in East and Central Africa to earn a doctoral degree, Wangari obtained a degree in Biological Sciences from Mount St. Scholastica College in Atchison, Kansas in 1964 and subsequently earned her Master of Science degree from the University of Pittsburgh two years later. Maathai pursued doctoral studies in Germany and the University of Nairobi, obtaining a Ph.D. in 1971 from the University of Nairobi where she also taught veterinary anatomy. She became chair of the Department of Veterinary Anatomy and an associate professor in 1976 and 1977 respectively. In both cases, she was the first woman to attain those positions in the region.

Professor Maathai was active in the National Council of Women of Kenya in 1976-87 and was its chairman from 1981-87. In 1976, while she was serving the National Council of Women, Professor Maathai introduced the idea of community-based tree planting. She continued to develop this idea into a broad-based grassroots organization whose main focus is poverty reduction and environmental conservation through tree planting. This organisation became known as the Green Belt Movement. Through this organisation, Professor Maathai has assisted women in planting more than 40 million trees on community lands including farms, schools and church compounds. Other countries that have successfully launched such initiatives in Africa include Tanzania, Uganda, Malawi, Lesotho, Ethiopia, Zimbabwe and others. She and the Green Belt Movement have received numerous awards, most notably the 2004 Nobel Peace Prize (a copy of her speech is available online here).

Wangari Maathai was internationally recognized for her persistent struggle for democracy, human rights and environmental conservation. Sadly, she passed away on the 25th of September 2011 at the age of 71.

Source: The Green Belt Movement

Mary Robinson

Mary Robinson was born on May 21, 1944 in Ballina, County Mayo, Ireland. Nominated by the Labour Party, Robinson became Ireland’s first woman president in 1990. She was the first head of state to visit Somalia after its civil war and famine in 1992 and the first to visit Rwanda after the genocide in 1994. In 1998 she was elected chancellor of Trinity College. She was the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (1997 – 2002).

Robinson was educated at Trinity College and King’s Inns in Dublin and at Harvard University in the United States. She served at Trinity College (University of Dublin) as Reid Professor of penal legislation, constitutional and criminal law, and the law of evidence (1969 – 75) and lecturer in European Community law (1975 – 90). In 1988 she established (with her husband) at Trinity College the Irish Centre for European Law. A distinguished constitutional lawyer and a renowned supporter of human rights, she was elected to the Royal Irish Academy and was a member of the International Commission of Jurists in Geneva (1987 – 90). She sat in the Seanad (upper chamber of Parliament) for the Trinity College constituency (1969-89) and served as whip for the Labour Party until resigning from the party over the Anglo-Irish Agreement of 1985, which she felt ignored unionist objections. She was also a member of the Dublin City Council (1979 – 83) and ran unsuccessfully in 1977 and 1981 for Dublin parliamentary constituencies.

Nominated by the Labour Party and supported by the Green Party and the Workers’ Party, Robinson became Ireland’s first woman president in 1990 by mobilizing a liberal constituency and merging it with a more conservative constituency opposed to the Fianna Fáil party. As president, Robinson adopted a much more prominent role than her predecessors, and she did much to communicate a more modern image of Ireland. Strongly committed to human rights, she was the first head of state to visit Somalia after it suffered from civil war and famine in 1992 and the first to visit Rwanda after the genocide in that country in 1994. Shortly before her term as president expired, she took up the post of United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (UNHCHR). As high commissioner, Robinson changed the priorities of her office to emphasize the promotion of human rights at the national and regional levels; she was the first UNHCHR to visit China, and she also helped to improve the monitoring of human rights in Kosovo. In 2001 Robinson served as secretary-general of the World Conference against Racism, Racial Discrimination, Xenophobia and Related Intolerance, held in Durban, South Africa. ( Sidebar: Children and Human Rights.)

After leaving her post at the UN, Robinson founded the nongovernmental organization Realizing Rights: The Ethical Globalization Initiative, in 2002. Its central concerns included equitable international trade, access to health care, migration, women’s leadership, and corporate responsibility. She was also a founding member of the Council of Women World Leaders, served as honorary president of Oxfam International (a private organization that provides relief and development aid to impoverished or disaster-stricken communities worldwide), and was a member of the Club of Madrid (which promotes democracy). In 2004 Amnesty International awarded her its Ambassador of Conscience award for her human rights work. Her other honours include the U.S. Presidential Medal of Freedom (2009). For more information on Mary Robinson’s current work, see The Mary Robinson Foundation.

Source: Biography.com

Florence Hagila

Florence Hagila is the local chairperson of SWAAZ (Society for Women and AIDS in Zambia) in her village Mulendi, Choma in Southern Province in Zambia. She is also a farmer growing tomatoes, maize, ground nuts and sweet potatoes. She volunteers at the local health center and visits the local community areas instructing people on how to use things like mosquito nets, on personal hygiene and family planning. She gets condoms from the health center and distributes them in the communities she visits.

Florence found that one of the main problems with the distribution of condoms was that when she gave them to women, their husbands refused to use them because they said that sex is not good when using a condom. So Florence changed her strategy. She decided to start distributing female condoms to the women instead and instructs them to put them in before the husbands get home, and then they will not notice it. She says that although some people may be HIV positive, they still have sexual feelings. She encourages them to use protection to stop further spread and re-infection. She feels that she is making progress because people are more open to talking about and using condoms. Some people still have reservations she says, but things are changing.

Florence received training from the Rural Health Centre where she volunteers and focuses on VCT (Voluntary Counseling and Testing) especially for couples. She remembers one couple where the man was positive and the woman was negative, and she counselled them on how to have safe sex and look after one another. This is typical of her work.

She became involved as a result of listening to a radio programme one day where a Catholic nun spoke about HIV and Florence realised that within her community, people did not have this information. She felt compelled to do something for her community, so she went to the Rural Health Centre and became a volunteer. She also helps to set up support groups to work alongside the Health Centre. That was two years ago and there are now are now nine support groups within the area covered by the Mulendi Neighbourhood Health Centre.

Florence visits people who are sick and who are taking ARVs (anti-retrovirals – a treatment for HIV). She goes to their house and helps them with cleaning and collecting fire wood, depending on how well that person is. She and the other volunteers offer advice and encourage people to socialise and not lock themselves away and get depressed. Sometimes they also cook for them.

“The world is cruel sometimes and that HIV and AIDS are not curable, but that it is not the end of your life. People can still have negative children if they are positive, so long as they find out how to protect their child, and follow the instructions they are given. I feel sad and angry about people who deliberately infect others”.

Despite her religious beliefs, Florence promotes the use of condoms. If people do not use condoms they will become infected and die, then there will be no one left to go to church. They are better off going to church alive and using condoms.

Source: This is What Has Happened

Taslima Nasreen

Taslima Nasreen was born in 1962 in Mymensingh, East Pakistan – now known as Bangladesh. As a young girl, she was always fond of literature and started writing herself when she was 15 years old. While studying medicine, she was the president of a literary organisation, after which she spent eight years working in hospitals. Her first poetry book was published in 1986, but it was her second book in 1989 that became a huge success and was offered regular columns in local newspapers as a result. She began to write about women”s oppression, criticising religion, tradition and the oppressive cultures and customs that discriminate against women. This won her many fans, but also many enemies. Islamic fundamentalists launched a campaign against her in 1990, staging demonstrations and marches. They broke into newspaper offices she worked in, sued her editors and publishers and put her life in danger by assaulting her publicly. She was no longer welcomed to public places or book fares because of this. In 1993 a fatwa was issued against her because of her criticism of Islam and she was confined to her house. The government confiscated her passport and asked her to stop writing if she wanted to keep her job as a doctor. Unfortunately, she was made to quit her job.

According to Taslima, what is needed is a uniform civil code that accords women equality and justice, not a religious one. Her views caused political and religious demonstrations and demands for her immediate execution by hanging. The government, instead of taking action against the fundamentalists, turned against her. A case was filed charging that she hurt people’s religious feelings, and a non-bail-able arrest warrant was issued. Deeming prison to be an extremely unsafe place, Taslima went into hiding.

In the meantime two more fatwas were issued by Islamic extremists, two more prices were set on her head, and hundreds of thousands of fundamentalists took to the streets, demanding her death. The majority who were not fundamentalists remained silent. Regardless, some anti-fundamentalist political groups did protest the fundamentalist uprising, but did not defend Taslima as a writer and a human being who should have the freedom to express her views. Only a few writers defended her rights.

But the international organization of writers, and many humanist organizations beyond the borders of Bangladesh, came to Taslima’s support. News of her plight became known throughout the world. Some western democratic governments that endorse human rights and freedom of expression tried to save her life. After long miserable days in hiding, she was finally granted bail but was also forced to leave her country. Her re-entry was denied, even when her parents passed away.

Taslima has been living in exile in Europe. She has written more than thirty books of poetry, essays, novels, and short stories in her native language of Bengali. Many have been translated into twenty different languages. Her applications to the Bangladesh government to be allowed to return have been denied repeatedly. One Bangladesh court sentenced her in absentia to a one-year prison term. The Bangladesh government has recently banned three other of her books, Amar Meyebela (My girlhood), Utol Hawa (Wild wind) and Sei sob ondhokar (Those dark days).

Writers and intellectuals both in Bangladesh and West Bengal went to court to ban her autobiography Ko (Speak Up) and Dwikhandito(The Life Divided). Two million-dollar defamations suits were filed against Taslima by her fellow writers. The West Bengal government finally managed to ban Dwikhandito on the charges of hurting the religious feelings of the people. A Human Rights organization in Kolkata filed a case against the West Bengal government for banning a book that is against freedom of expression. After two years, the ban was lifted by the Kolkata High Court, which, Taslima says, is a victory for freedom of expression.

The numerous prestigious awards she has received in western countries have resulted in increased international attention to her struggle for women’s rights and freedom of expression. She has become a symbol of free-speech. Taslima has been invited to speak in many countries and at renowned universities throughout the world. Her dreams of secularization of society and secular instead of religious education are becoming increasingly more accepted and honoured by those who value freedom. Taslima was forced to leave Bangladesh for Europe. After a decade, when she was granted a visa, she visited India, her second home. When she was granted residence permit, she moved there. But only after 3 years of living in West Bengal, because some Muslim extremists wanted her to leave India, the West Bengal Government and the Indian Government forced her to live under house arrest and put pressure on her to leave the country. She was forced to leave India after being confined for seven and half months. The real tragedy is that two countries which give her the oxygen of language have cut her off. It’s not the geography alone, but the languagescape also. That’s the real crime… a fish being made to live on land. She does not have a home.

Source: https://taslimanasrin.com/index2.html

The International Bill of Rights for Women – CEDAW (Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women)

The Basics

The Convention of the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women was adopted in 1979 (and is more commonly known as an international bill of rights for women). It recognises that discrimination against women prevents them from enjoying their political, social, economic, cultural and civil rights and freedoms – their basic human rights. The Convention establishes the Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW), a committee of 23 independent experts which reviews reports that state parties are required to submit every four years, indicating the measures taken to implement the women”s convention. State parties to the Convention have a three-fold obligation as regards the rights of women:

- Respect: The state must abstain from any conduct or activity of it’s own that violates human rights.

- Protect: The state must prevent violations by non-state actors including individuals, groups, institutions and corporations.

- Fulfil: The state must take whatever measures are necessary to move towards the realisation of women’s human rights.

CEDAW Made Easy

- All human beings are born free and equal in rights and dignity

- Despite this fact, discrimination against women continues to exist

- In situations of poverty, it is women who are worst hit – also known as the “feminisation of poverty”

- For a country to fully develop and maximise it”s potential, its women must fully participate and be treated as equal to its men

- In order to eliminate discrimination against women, there will have to be changes in the traditional role of men and women within society.

CEDAW – A Summary

Article 1 – Defines discrimination as:

“…any discrimination, exclusion or restriction made on the basis of sex which has the purpose of impairing or nullifying the recognition, enjoyment or exercise by women, irrespective of their marital status, on the basis of equality of men and women, of human rights and fundamental freedoms in the political, economic, social, cultural, civil or any other field.”

Article 2 – Duty of the State: The state must ensure the elimination of any discriminatory laws, policies and practices within the national legal framework.

Article 3 – Equality: The state must also take measures to uphold women”s equality in all fields.

Article 4 – Temporary Measures: States are allowed to implement temporary measures, if this means the acceleration of women”s equality.

Article 5 – Culture: Discriminatory cultural practices or traditions must be abolished by the states.

Article 6 – Trafficking: States must take the appropriate steps in order to suppress the exploitation involved in prostitution and in the trafficking of women.

Article 7 – Political and public life: Women must have equal rights to vote, hold public office and participate in civil society.

Article 8 – Government Representation: Women must be allowed to work and represent their governments at international level.

Article 9 – Nationality: Women have the right to acquire, retain or even change their nationality as well as that of their children.

Article 10 – Education: Women have equal rights with men with regards to access to education.

Article 11 – Employment: Women have equal rights with men in employment (including equal pay, healthy working conditions etc)

Article 12 – Health: Women have equal rights to health care with an emphasis on reproductive health services.

Article 13 – Economic and social life: Women have equal rights to family benefits and financial credit, as well as the right to participate in recreational activities.

Article 14 – Rural women: Rural women must have the right to adequate living conditions, participation in development planning and access to healthcare and education facilities.

Article 15 – Equality before the law: Women and men must be seen as equals before the law. Women have the legal right to own property and chose their place of residence.

Article 16 – Marriage and the family: Women have equal rights with men within marriage, including family planning.

Articles 17-24: refer to the functioning role of the Committee on CEDAW and reporting procedures.

Articles 25-30: refer to the administration of the Convention.

Further information:

For more info on CEDAW: https://www.un.org/womenwatch/daw/cedaw/

The Issue of ‘Reservations’

Upon signing and ratifying CEDAW, states have the right to enter reservations outlining a number of areas where they argue the provisions of CEDAW do not apply nationally; these reservations include a number of recurring, significant issues including:

- Where CEDAW would conflict with Shariah law and its different interpretations (e.g. Bahrain, Bangladesh, Iraq, Libya, Morocco, Oman, Pakistan, Syria etc.) or with other religious issues (e.g. Israel and the issue of women judges in religious courts etc.)

- Where the provisions of CEDAW contradict national legislation as regards family laws or codes (e.g. as regards a child”s nationality being decided by that of the father rather than the mother, where all marriages must be registered or where the right of women to freely choose their domicile is restricted etc. Algeria, Egypt, India, Kuwait, Morocco etc.)

- Where governments insist that national legislation is more favourable to women than under CEDAW (France, UK, Ireland etc.)

- Where family legislation confers more favourable rights on women than men (e.g. Ireland, UK etc.) or on men rather than women (e.g. Malta on women”s income – seen as part of that of the man or on social welfare being paid to the head of household deemed to be the man)

- Where CEDAW challenges traditional customs and practices which take time to change and which are unlikely to change as a result of direct legislation (e.g. Niger)

- Many states reject the jurisdiction of the Court of International Justice in disputes between states parties outlined in article 29

For a more detailed discussion of these reservations by state, see https://www.un.org/womenwatch/daw/cedaw/reservations-country.htm

CEDAW Today

CEDAW is a tool for countries to use in order to achieve progress and equality for its women and girls. It is also a very practical tool for campaigners and activists to challenge discriminatory, outdated or traditional pieces of national legislation. Providing equal opportunities for women and girls to be educated, work and participate in decision making can also assist in the reduction of violence against women, the alleviation of poverty and strengthen a country’s economy. In countries that have ratified CEDAW, women have worked with their governments at policy level to create better opportunities for women. For example:

- Educational opportunities: Bangladesh used CEDAW to help attain gender parity in primary school enrolment and has set a goal for 2015 to eliminate all gender disparities at secondary level also.

- Violence against women and girls: Mexico used CEDAW terms in a General Law on Women’s Access to a Life Free from Violence in response to a growing epidemic of violence against women. By 2009, all 32 Mexican states had adopted the measure.

- Marriage and family relations: Kenya has used CEDAW to address differences in inheritance rights, eliminating discrimination against the (female) family of the deceased.

- Political participation: Kuwait’s parliament voted to extend voting rights to women in 2005 following a recommendation by the CEDAW committee to eliminate discriminatory provisions in its electoral law.

Source: www.cedaw2011.org

To date, 186 countries have ratified the Convention and 99 have ratified the Optional Protocol which recognises the competence of the Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women (the committee that monitors States compliance with the Convention) to receive and consider complaints from individuals or groups; this allows individual women, or groups of women, to submit to the Committee claims of violations of rights protected under the Convention (if and when domestic remedies are exhausted) and it also allows the Committee to undertake inquiries into grave or systematic violations of women’s rights.

Further Information

For further information on countries which have ratified CEDAW, see treaties.un.org

The Role of Men

Men, Gender & Development

It is a universal fact that women’s experience of human development over many decades has yet to deliver on the ultimate goal of gender equality. This section on women attests to this reality. Women continue to experience multiple oppressions in all spheres of their lives, across all continents. Men are generally considered the perpetrator and women the victim. The flurry of recent research on Gender Based Violence – particularly in Africa and in conflict situations such as Darfur or the Congo, fuels this argument.

The assumption that men benefit from human development, by virtue of their being men is unhelpful and unprogressive. What was interesting about the thinking behind the feminist movement to Gender and Development (GAD) in the 1980s was the realisation that not all men reaped the benefits of human development. Even within the social category “men” there are layers of men who experience violence or are subordinate within this category – for example gay men. Boys and young men also experience the trauma of unsafe practices around circumcision for example, where “going to the mountains” to be circumcised in order to become “men” could cost them their lives. There is also the reality, often lost in the discourse that links violence with men, is that not all men are rapists or violent, and their experiences of human development can be (and often is) negative. The realities of an evolving global environment, can mean that development negatively impacts on men”s lives and challenges their understandings of their “traditional” male roles, leading to what some are calling the “crisis of masculinity.” So “Gender” as a social category is important for women AND men.

There is a growing interest in international development which considers the need to engage with men – the “missing other half” – as “part of the solution” to women’s development, particularly in response to escalating unemployment, male perceptions of women’s rights challenging traditional male roles and rising occurrences of Gender Based Violence. However, involving men in women’s development is a political hot potato within the Gender and Development agenda. As a political agenda in a female occupied space, there are concerns among feminists that involving men in GAD may well lose this focus. There is resistance among feminists wanting to protect this space and the fear that men may “take over” the hard work that women have fought so hard to achieve. Power relations are central to engaging with men at the political and theoretical level, and also at the economic level – what happens to the already scarce resources available to women?

There”s a realization that if we don’t bring men

in as partners, we won’t win the battle.

Sheila Meintjes, Commission on Gender Equality in South Africa.

There is however, also a school of thought that believes engaging with men in GAD can benefit towards the ultimate goal of gender equality. Despite the political wrangling around GAD interests, at the practical level, men are already very much a part of “women’s development” being very much a part of women’s groups, community and national projects in developing countries in Africa for example. The reality on the ground is that men are a part of women’s lives and finding ways to channel men”s engagement in women’s empowerment is the real challenge.

One example of this in action is the One Man Can campaign pioneered by the Sonke Gender Justice Network in South Africa. Sonke is a gender focused non-governmental organisation, who quickly realised that involving men was a crucial element in their work towards gender equality:

If a woman is living in an abusive relationship…then to empower her with awareness of her rights… is not always a wise thing. Women return from workshops with new clarity, wanting to assert their rights. The result? The men begin to regard themselves as the victims. Fearing the unknown, they become even more violent towards their partners.

Bafana Khumalo, Sonke Gender Justice Network.

Within the South African context, Gender Based Violence (GBV) is a widespread reality, so much of the focus on men’s trainings have been on the involvement of men in challenging traditional male stereotypes and preventing sexual violence at all levels. Their One Man Can project promotes the role of men in challenging and changing male norms:

As young men, we have a particular responsibility to challenge the violence that some men do to women and girls we know and care about – our sisters, friends, classmates and neighbours.’

Sonke ‘encourage men to work together with other men and with women to help create a better, more equitable and more just world, and through encouragement to get involved in the struggle to prevent HIV and AIDS and violence against women.’ The working with women is an important learning in engaging with men in development. Change needs to be understood by both men and women. For example if a man who formerly is abusive suddenly after being included in empowerment and change projects decides to clean the house and looks after the children their partner must also understand this change as not ‘chastising her for not looking after him or the house well enough’ or see his consulting on decision-making in the home as not being ‘man enough to make decisions anymore?’ (Sonke).

Case studies of working with men towards change

The story of Sonwabo – challenging the stereotype that men are not involved in efforts to promote testing and care:

‘I am from Shawbury, here in Eastern Cape. I had a wife, but she died some years ago of pneumonia. When she passed on, I stayed with my children. Then I found a girlfriend, and we were happy together for almost a year, until a friend of mine took her away from me. I used to cry the whole night.

I also used to cough all the time. I was one of those men who did not believe in going to the clinic, because men are not treated well there. I also thought that men must be strong, that doctors were for women and children. But I forced myself to do it, because I could see that I was getting seriously sick. I asked a nurse to test me for TB. She said, “Don”t you want to test for HIV?” I said, “I want to test for everything.” On that day, I learned that I am HIV+.

As I was leaving the clinic, I asked myself, “Who else will love me?” You see, at the time, HIV was not well known. But I have found someone to care for – she is also HIV+. We are faithful to each other, and we use condoms so that we do not re-infect each other. As I am speaking, we are both taking ARVs now – we do not skip any days, and we take them at the right time each day.

At our support group, at first I was the only man. That was not good for me, because I wanted to speak with other men. No men in my area wanted to test for HIV in 2002. But I was patient, and waited with hope, and slowly they arrived. Today, we talk about HIV. We want to make sure that the beating of women does not happen. We want to make sure that everyone is taken care of. We are working very hard, to ensure that our villages are places where people feel safe and healthy.”

Mzolisi”s Story on shifting men”s attitudes towards women:

‘…You might not know it from looking at me, but I used to be an out of control gangster. I used to think that men were better than women… that women should do what men say. I used to sleep with many women, thinking that made me a real man. One day not long ago, I was very angry and became my rude self towards my sister. I was hungry, and I started to beat her until she bled. The reason was that she had not cooked dinner for me. I was sentenced to five months in jail.

When I came back, I started to feel cold. I shivered all the time. My mother took me to a traditional healer, who told me, “You have been bewitched by alcohol.” She gave me three bottles: one for vomiting, one as a laxative, and the other for sweating. I paid R500′ (approx €50).

I used those bottles, but I could see no improvement at all; instead I was getting seriously sick.

The doctor I went to told me the real reason for my sickness was TB. I started and continued with my treatment for four months. Then I got tested for HIV. I tested positive. My CD4 count was only 73, but the doctors told me I should first finish the TB medication before starting ARVs.

The support group I belong to is helping me, because we advise one another and talk about how to take ARVs. I also see my colleagues get stronger by the day. We talk about what it means to be a man, and about women’s equality. We know we must be faithful to our partners and that we must use condoms. Today I know women are as important as men, and I would never raise a hand against them. My sister and I are on good terms now. We are very close to each other.

Mlungisi”s story on adopting new models of fatherhood:

‘I remember living without a father. There were two of us children at home when we were growing up. My father would come back sometimes and sometimes he would not. That caused a lot of misery at home. I went to find work in Capetown in 1972. I came back home with the aim of getting married. I drank alcohol, doing things that I think caused a lot of trouble or pain in my family because there was no other man around the house who could advise me when I did wrong things.

As the years went by I noticed that my health was not good, and my body was getting thinner and thinner. My sister asked me to go to the clinic. I found out then that I am HIV+ in 2002. I was shocked, knowing that in the next week I might die. I had heard that someone who has AIDS does not live for even a week… I started taking ARVs in 2004. What hurt me was that men here in Mpumazo refused to eat from the same bowl as me. My sister encouraged me by saying that I must regularly take my treatment, because that will make me better.

Because of loneliness, I asked whether there are other people suffering from the same thing I have, so that I can spend time with them instead of being insulted all the time in the village. I then went to the support group in Qumbu, where I got assistance. The help I needed was emotion, to strengthen me.

Today I cook and look after the children because my wife has already passed on. I remember living without a father. Times have changed. I am a different father from that one who left us struggling.

Source: These case studies are taken from Sonke Gender Justice Network

Have a look at People Opposing Women Abuse”s (POWA) challenging and brilliant video on domestic violence. A social experiment was set up in a townhouse complex in Johannesburg to firstly, find out how people would react in this certain circumstance; and secondly, to get people talking about the issue of violence against women and how you, as an individual would react.

Fran Luckin, the advertising executive who created the film, said “We weren”t sure what was going to happen. We were astonished…It was a real eye-opener. I think nobody really believes that someone dies in a domestic argument.”

Have a look and ask yourself, what would you do? Would you challenge it directly? Or is that someone else”s job?

Further Reading

Resources for further research and learning:

Refers to a range of learning resources – films, novels, documentaries, reports and other DE type resources

Wikigender – Wikigender is a project initiated by the OECD development Centre to facilitate the exchange and improve the knowledge on gender equality-related issues around the world. Wikigender aims to highlight the importance of social institutions such as norms, traditions and cultural practices that impact on women”s empowerment.

The Association for Women”s Rights in Development – AWID is an international, multi-organisational, feminist, creative, future-orientated membership organisation committed to achieving gender equality, sustainable development and women”s human rights. Their website has a wealth of information including news on women”s rights, resources and publications, initiatives and information on how to get involved.